Why we all stall in wild markets

Why does it hurt so much to lose money as markets fall but equivalent gains barely inspire a smile?

The answer has to do with people’s perception of risk and the sometimes irrational value they place on assets. Here’s an example:

John paid $20 for an asset and is happy two months later to see its market value has increased to $25, a 25% gain. Mildly pleased with himself, he chooses to do nothing.

On the other side of town is Elizabeth, who paid $20 for a different asset and is horrified to see the market value of her investment steadily drop to $15, a 25% loss. She teeters on the brink of selling.

In the cold language of professional investors John’s and Elizabeth’s investments have performed within the same “risk” parameters, where risk is the variance from expected returns. In that definition, risk is a backward-looking measure.

Our two investors are forward-looking, however, and John’s expectations will have risen whereas Elizabeth will feel despondent.

FROZEN IN THE HEADLIGHTS

If they were clear-headed individuals, John would sell and take a profit above what he’d expected for such a short holding period and Elizabeth would buy more of the same asset if she believed her own valuation of it at the outset.

In the real world, however, John will twiddle his thumbs as the price probably goes sideways for ages or loses value, and Elizabeth will be paralyzed by the prospect of “taking a loss” as she clings to the belief that the market will come to its senses and agree with her “correct” valuation. In her mind, selling will “crystallise” the loss she already sees on her screen.

(Such irrational behaviour is well known, and anyone wishing to learn about how humans reach decisions should read Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow.)

IRRATIONAL RETURNS

The experience of John and Elizabeth occurs en masse when investment markets rise or fall sharply. In both cases the same thing is happening — prices are performing outside expectations — but the mood of investors, or “market sentiment” to use the media lingo, will be wildly different depending on the direction of the change.

When risk of loss is felt to be low, investors will downplay the volatility because the price direction is upwards. But the same level of volatility will cause great alarm in the media if prices are dropping.

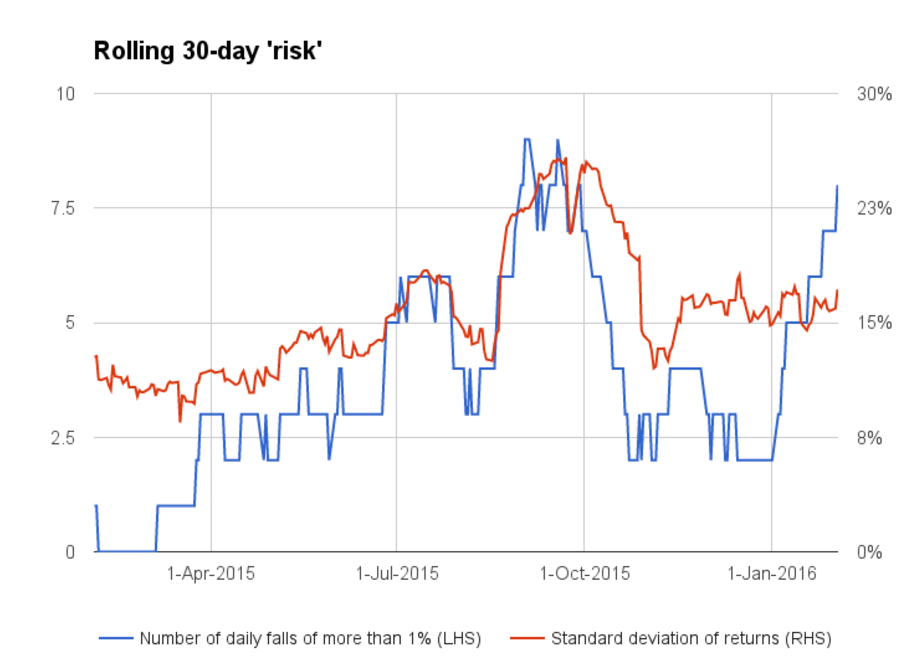

The chart shows a classic example, comparing January 2015 with January this year.

The variance of returns remained fairly constant over the period (not including mid-August to mid-October), but the frequency of large daily losses — the blue line — rose and fell.

The data starts at the end of January 2015 and shows rolling 30-day market risk, being variance of returns, and what investors would more likely recognise in their gut as risk, being the number of days during which the ASX200 lost more than 1% value.

GOOD TIMES, BAD TIMES

The start of 2015 was terrific time for investors — by the end of February the ASX200 had gained almost 10%. Annualised risk levels were in the low teens (the red line) and it felt like there was no chance of daily drops of more than 1% (the blue line).

A year later we have a different story. Risk levels are slightly higher, hovering above 15%, but the expectation of large daily losses has sprung upwards. By January 31, the ASX200 had lost at least 1% market capitalisation on eight of the previous 30 days.

At the end of January, the ASX200 had lost nearly 5.5% for the calendar year to date.

CHECK YOUR BEHAVIOUR

So, how could we expect the typical “irrational” investor to have responded?

If it’s early 2015, all those great gains were probably greeted with a smile and nothing more. From what we know now, it would have been a great time to sell.

If we’re talking about January 2016, an unusual run of sharp losses will have put nerves on edge. Many investors would have been asking themselves how much more of this they can take.

Investing is all about accepting risk. The more risk you take on, the higher the expected return (or at least that’s how it should work, and that’s how most people understand it).

But the market definition of risk says the variance of returns goes both ways: up or down. If investors understand that, then their conviction will be tested when prices are falling sharply or rising faster than expected. Both environments could offer opportunities, and ones that may not be immediately intuitive.

Frequently Asked Questions about this Article…

Losses in the stock market feel more painful than gains because of our perception of risk and the irrational value we place on assets. While gains might bring mild satisfaction, losses can cause significant distress, leading to emotional decision-making.

Investors often react irrationally to unexpected market changes. When prices rise, they might hold onto assets longer than planned, hoping for more gains. Conversely, when prices fall, they may hesitate to sell, hoping the market will recover, despite the risk of further losses.

Backward-looking risk measures the variance from expected returns based on past performance, while forward-looking risk considers future expectations and how investors feel about potential gains or losses.

An investor might choose not to sell an asset after a gain due to a belief that the asset will continue to increase in value, or simply because they are mildly pleased and prefer to hold onto it rather than crystallize the gain.

Market sentiment refers to the overall mood of investors, which can be optimistic or pessimistic depending on market trends. It affects investor behavior by influencing decisions to buy or sell based on perceived risk and potential returns.

Understanding market risk, which includes the variance of returns, helps investors make better decisions by preparing them for both upward and downward market movements. This awareness can lead to more rational decision-making and the identification of potential opportunities.

Volatility plays a significant role in investment decisions as it represents the degree of variation in asset prices. High volatility can lead to emotional reactions, but understanding it can help investors manage risk and identify potential buying or selling opportunities.

Investors can avoid irrational behavior during market fluctuations by staying informed, understanding their risk tolerance, and maintaining a long-term perspective. Learning about behavioral finance, such as concepts from Daniel Kahneman's 'Thinking Fast and Slow,' can also help in making more rational decisions.