Most floats lose money, but you can hit the jackpot too

Snap’s shares, which gained 44pc on its March debut, is trading well below its issue price.

Investors who bought into the initial public offering of the US social media group Snap in early March had a chance to almost double their money on day one.

Issuing its shares at $US17, Snap’s shares surged almost 75 per cent on March 3 to a peak of $US29.44 before closing the day at $US24.48 — a 44 per cent gain.

But almost as fast as a disappearing Snapchat phone message, those who bought into the IPO and who are still holding their shares have watched their returns vanish over the past five months. Snap shares fell below their issue price last month, dipping to an lowest of $US12.10 on Thursday.

Snap’s market snap is a potent lesson for all investors in stockmarket IPOs. Making a quick profit, like the large institutional fund managers who bought into Snap and sold out straight away, is possible. But it’s not guaranteed, and retail investors can get badly burned.

Over the first six months of 2017, the average day one premium on the IPO listings that have hit the Australian market boards has been 9 per cent. But out of 50 ASX floats in the first half of this year, more than half (30) are now under water — trading below their IPO issue price per share — and several are just above break-even point. Data from IPOwatch shows a dozen out of the total number of listings are between 30 per cent and 60 per cent down on their float price, and another 13 are down between 10 per cent and 25 per cent. In other words, many investors in IPOs this year have done their dough, even more so than those who bought into Snap.

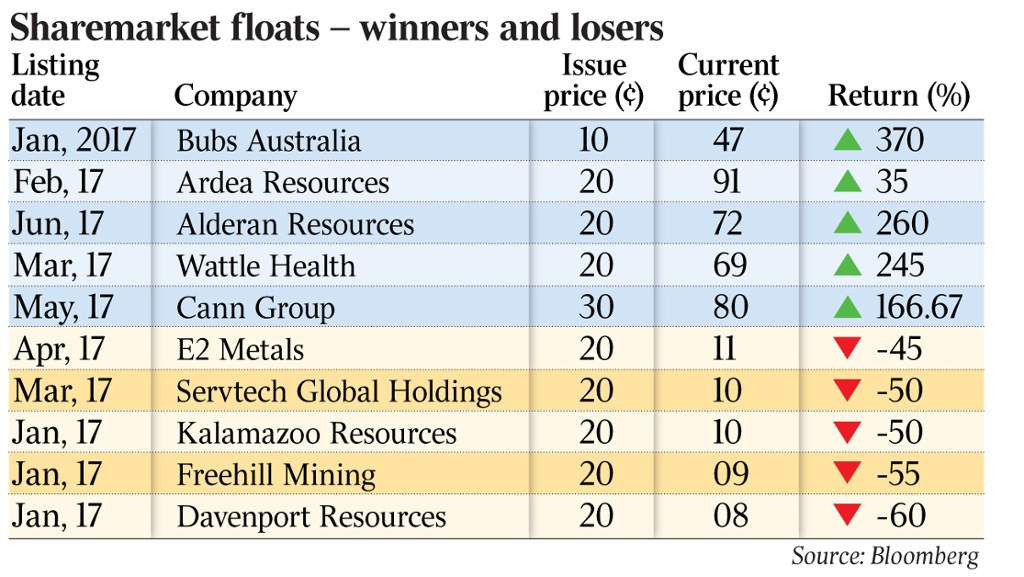

On the other side of the ledger, five IPOs have soared more than 150 per cent above their float issue price, with goat milk baby formula company Bubs Australia the strongest performer, up 370 per cent. Not far behind is cobalt explorer Ardea Resources, up 355 per cent, and copper explorer Alderan, up 260 per cent.

Another six are trading between 30 per cent and 60 per cent up on their listing prices, and four are more than 20 per cent higher.

Missing in action

Not all IPOs are created equal. What’s clear from the data is that many of the companies that have listed on the ASX so far this year are micro caps, with market valuations of less than $10 million.

Out of the top performers, only one — investment bank Moelis Australia (at $560m) — is worth more than $100m. It has returned an impressive 81 per cent since listing in April.

The biggest float of the year, waste management group Bingo Industries, is worth around $647m but has only returned just over 3 per cent since listing in May. Healthcare group Oceania, worth $624m, is up about 30 per cent.

In the bigger companies, buying in and selling out isn’t too much of an issue for investors. But in the very small ones, liquidity is often a problem. Buying into the IPO can be easy, but getting out can be much harder if there’s not a lot of demand. Often the major shareholders have full control, so there’s little incentive for them to buy more stock.

Of 10 floats scheduled to list on the ASX in August, six are seeking to raise less than $10m.

HLB Mann Judd partner, Marcus Ohm, expects a higher number of listings in the second half. But he also notes that there has been an absence of large floats.

The two IPOs listed for September are among the bigger ones so far this year. Hedge fund VGI Partners is seeking to raise $300m, while fund manager Fat Prophets is pitching for $220m. Because bigger ASX listings have been missing to date, the total value of amounts raised is lower compared to this time last year ($1.9 billion versus $2.5bn). “A significant portion of companies that have applied to list in the second half of the year are also small caps, therefore it is possible that we will see a meaningful drop in the total amounts raised in 2017 compared to recent years (2016: $7.5bn, 2015: $7.02bn),” Ohm says.

“This time last year, we had seen two companies list with a market capitalisation of around $1bn and 11 companies list with a market cap over $100m. So far in 2017, there has only been one listing with a market cap greater than $500m, and seven with a market cap between $100m and $500m.”

Lessons for investors

In May, Wesfarmers pulled the $1.5bn float of Officeworks, with the impending arrival of online retail behemoth Amazon spooking investors.

“The current pipeline of listings for the remainder of 2017 does not show any particularly large listings on the horizon,” Ohm says. “As at June 30, 21 companies have applied to list and junior exploration companies are likely to be a strong contributor, particularly the materials sector which currently has 10 proposed listings, seeking to raise a total of $75.5m.”

The ASX IPO scorecard for 2017 to date is really nothing to gloat about. And even with some of those more speculative stocks, the returns could quickly disappear if market conditions change due to factors such as negative commodity price movements.

For retail investors, the most important thing to recognise is that buying into an IPO does not automatically translate into a profit. In fact, more newly listed stocks end up going backwards than forwards. Read the IPO prospectus carefully before applying for shares. Understand the business as much as possible, including what it does, its management expertise, as well as its financials, and tread very carefully.

Frequently Asked Questions about this Article…

An IPO, or Initial Public Offering, is when a company first sells its shares to the public. For everyday investors, it offers a chance to buy shares early, but it's important to understand that not all IPOs guarantee profits. Reading the IPO prospectus and understanding the company's business and financials is crucial before investing.

IPOs can lose money due to various factors such as market conditions, company performance, and investor demand. Some IPOs succeed when the company has strong fundamentals, a solid business model, and favorable market conditions. However, many newly listed stocks can decline in value, so careful research is essential.

Snap's IPO initially performed well, with shares surging 75% on the first day. However, the stock later fell below its issue price. The lesson for investors is that while quick profits are possible, they are not guaranteed, and holding onto IPO shares can lead to losses if the company's performance declines.

Micro-cap IPOs, which are companies with market valuations under $10 million, often carry higher risks due to lower liquidity and potential volatility. These stocks can be harder to sell if demand is low, and major shareholders may control the market, making it challenging for retail investors to exit their positions.

In 2017, the materials sector, particularly junior exploration companies, has been a strong contributor to IPO activity. However, the overall number of large IPOs has been lower compared to previous years, with many smaller companies seeking to list on the ASX.

Retail investors can protect themselves by thoroughly reading the IPO prospectus, understanding the company's business model, management expertise, and financials. It's also important to be cautious and not assume that buying into an IPO will automatically result in profits.

Market conditions can significantly impact IPO performance. Factors such as commodity price movements and overall economic conditions can affect the value of newly listed stocks. Investors should be aware that even speculative stocks with initial gains can quickly lose value if market conditions change.

Yes, some standout IPO performers in 2017 include Bubs Australia, which saw a 370% increase, and Ardea Resources, up 355%. These companies have significantly outperformed their float issue prices, highlighting that while many IPOs may struggle, there are opportunities for substantial gains.