Don't worry about the property doomsayers

Summary: The premise that house prices will fall next year looks on shaky ground given the fundamentals of a growing economy. Credit growth is still low relative to history, while mortgage rates are still very low. There is a lot of misinformation on the issue of Chinese investors. |

Key take-out: The idea that there will be a collapse in house prices next year doesn't have much factual support. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Residential property. |

Most analysts now agree that the prospects for a domestic recession are dwindling. Consumer and business confidence is rising and as the RBA's Deputy Governor Philip Lowe noted himself in a speech yesterday on Australia's economic fundamentals: “My central message is that these fundamentals are strong and that they provide us with the basis to be optimistic about the future.”

The recession call now focusses squarely on one event, a housing market collapse. As many of you will already know, that received a lot of attention this week. A number of investment banks argued that the housing market was turning, with Macquarie in particular predicting that the 7.5 per cent housing price fall would commence from March next year.

Westpac's decision to lift lending rates to owner-occupiers and investors by 0.2 per cent would also appear to add to that case.

More generally, the key propositions for those who think the property market has turned include the following:

- We're at the peak of the credit cycle

- That investors, who had been driving the market, are now being hit by macro-prudential tightening, and rate hikes on investor mortgages

- That there has been a drop off in Chinese demand from a weaker Renminbi and capital controls

- Weaker population growth

Now I've dealt with the last point on weaker population before (see Putting this property market in perspective, September 16). Housing construction has been insufficient to deal with population growth for more than a decade. So a period of overbuild now isn't a problem unless it runs for many years. In the US for instance the boom went for five years or so and that wasn't off an underbuild. In Spain and Ireland you're talking more a decade. Now compare that to Australia we're not even one year into it – and that doesn't even come close to offsetting the previous decade of underbuilding.

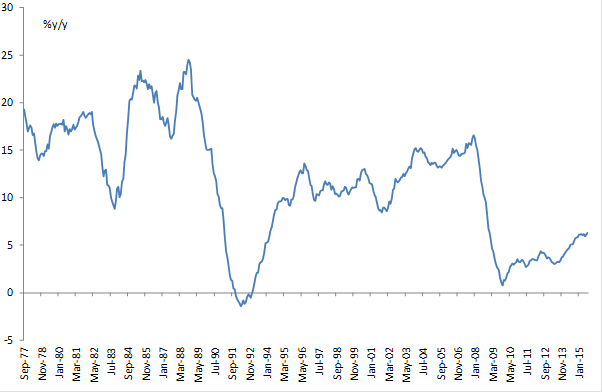

As for the peak in the credit cycle, this is extremely unlikely. Take a look at chart 1 below. The first thing to notice is that credit growth is currently accelerating, not decelerating. Indeed there is no sign of a slowing either in annual growth rates or monthly growth rates. Both are still rising.

Next, notice that credit growth is still low relative to history. Very low.

Chart 1: Credit growth is still low

Source: RBA

Plenty of people will argue that this low credit growth is due to high levels of debt and extremely high house prices. But that doesn't seem plausible. Consider that from February 2004 to July 2007, annual credit growth averaged over 14 per cent. All the arguments that are used now to suggest that credit growth has peaked, were equally as valid then – yet we had double digit growth. In particular, house prices were at a record, household debt-to-incomes were at a record, over 160 per cent, and debt servicing rates were similar. The key difference between now and that period, is that household savings rates are so much higher now – close to 10 per cent, compared to about zero per cent back then. Realistically, consumers are in a better position now than they were then.

As for suggestions that investors are being hit, this isn't quite accurate. Sure, system lending growth to investors has apparently been capped by regulators at 10 per cent, and new investors are paying higher rates on loans. Yet rates are still very low – even despite Westpac's move to lift rates today.

All we are seeing in response to that is a switch in loan classification. What analysts and bureaucrats forget is that a good chunk of the supposed investor market was in fact owner-occupiers. It was a common strategy for owner-occupiers to temporarily rent out new purchases. This is changing as more supply comes on board and rental yields drop. Similarly, the decision to restrict lending to investors and to force then to pay higher rates is also affecting the decision of owner-occupiers to temporarily rent out their residence.

So naturally loan classifications are changing from investor loans back to owner-occupier loans.

This is why we saw a surge in lending to owner occupiers last month. Excluding the huge post-GFC rebound, we've seen the strongest lending to owner-occupiers since 2001. It all coincided with the restrictions and out of cycle rate hikes placed on investors.

On the next issue of Chinese investors. It seems that there is a lot of misinformation on this front. Don't forget that a parliamentary inquiry last year found that there was no evidence to suggest that foreigners, Chinese or otherwise, are bidding up prices. A finding supported by recent research from the University of Sydney that suggests only 2 per cent of purchases reflect Chinese buying.

Thus far then the premise that house prices will fall next year is already looking on shaky ground given the fundamentals we've got: A growing economy, ultra-low rates, a low unemployment rate.

Now house prices do fall, on some measures. Comparing one quarter in any given year to the quarter a year ago shows that since the late 1980s house prices have declined about three or four times. In each case though, either high interest rates or some global crisis drove prices lower. The biggest fall we've had since that time was only 5 per cent – and that was during the GFC.

So a fall in house prices from 7 per cent from March next year – just because – isn't likely. In any case if you look at average annual house prices in nominal terms – house price don't typically fall. Analysts need to make all sorts of adjustments to the data – constant quality, inflation adjusted etc to get price declines. It's debateable as to how appropriate those adjustments are or what real value they have for the question at hand.

As a final point, it has to be noted that global institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) don't really find that there is too much wrong with house prices in Australia. That the IMF can't find much that is wrong is telling – because they don't need much of an excuse to find a crisis somewhere. They thrive on it.

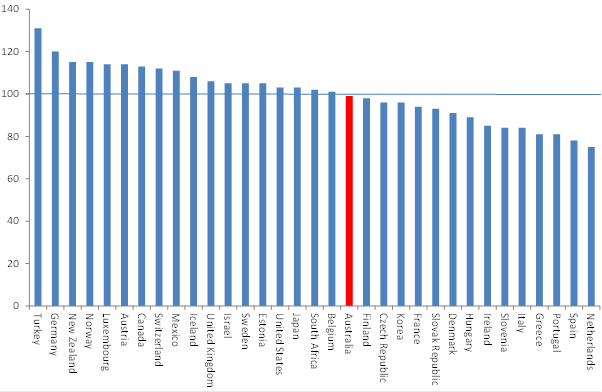

Chart 2: Price-rent-ratio (index 2010 =100)

Source: IMF and OECD

Chart 2 above shows that since 2010, house prices haven't really increased relative to rents since 2010. There has been a very modest fall. Indeed for all the talk of house prices surging in Sydney, rents are also very high.

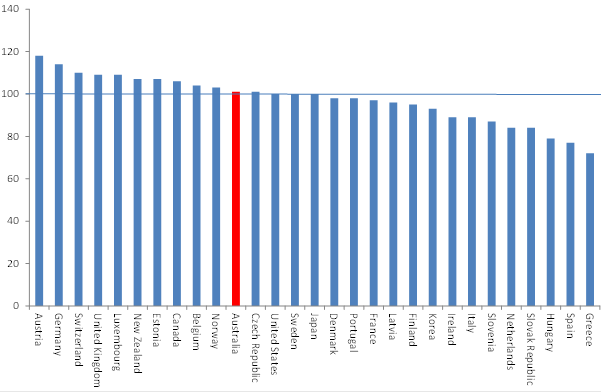

Finally, chart 3 below show that in the IMF's estimation, house prices haven't really increased relative to incomes since 2010.

There's a lot of hysteria over house prices and the housing market in general. Not much of it is based on any evidence or research. Certainly the idea that the housing market has peaked, or that there will be a collapse in prices next year, doesn't have much factual support. Nothing even hints at that at the moment.

Chart 3: Price-income-ratio (index 2010 =100)

Source: IMF and OECD