Will you be the last one out of coal?

Summary: A number of global and local institutions have announced that they are reducing their exposure to fossil fuels on financial grounds, with pure-play coal stocks coming under focus. Other institutional investors are quietly positioning their portfolios or considering the best response. Actions range from full divestment to partial selling or engagement with companies. |

Key take-out: Although no-one knows exactly when climate change will become an issue affecting investors, some investors are moving now to avoid being the last one out. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Coal. |

Ethical and activist funds have been cooling on fossil fuels such as coal and oil for years, but over the last year the speed and scale of the exit of major investors from coal has been alarming… even for veteran market watchers.

Now the question – especially for coal – is whether the latest sell off is not just another cyclical downturn but something bigger? It may be the beginning of a wholesale exit from the coal market, a move which would finish this commodity as an option for most investors. (To read more about demand for coal, see Tim Treadgold's article today: Is coal the new tobacco?)

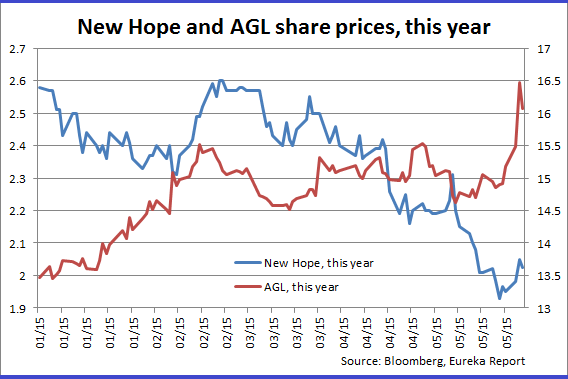

Certainly the range of powerful interests now exiting the coal market is extensive. Perhaps the most spectacular move came last month from energy giant AGL which announced it was planning a close down of its existing coal-fired operations by 2050 and said it would not “build, finance or acquire new conventional coal-fired power stations in Australia”.

Geoff Cousins, one time chief of Optus and adviser to Liberal Prime Minister John Howard, now the President of the Australian Conservation Foundation, articulates the key issue facing investors: “When they (AGL) say they'll be completely out by 2050, they don't mean, by 2049 they're suddenly going to divest themselves. It's going to happen progressively and probably a great deal more rapidly,” Cousins says.

Cousins says a “severe” rerating of fossil fuel companies could also happen quickly. “One day you'll get two, three, four analysts saying it's time to go and then the investor gets caught.”

The story so far

The global fossil fuel divestment movement appears to be gathering momentum. Pledges to restrict investments in fossil fuel stocks have come from around two dozen US universities, UK universities including Oxford, and a string of local councils and philanthropic foundations around the world. Norway's Government Pension Fund has reduced its exposure, as have the heirs of oil tycoon John D Rockefeller. Saudi Arabia's oil minister has flagged a phase-out of fossil fuel use by the middle of the century. Former Goldman Sachs CEO and US Treasury secretary Henry Paulson and former hedge fund manager Tom Steyer launched the Risky Business Project to quantify the economic risks of climate change, while hedge fund founder George Soros announced a $US1 billion investment in clean energy technology.

Although some calls are on ethical grounds, many have a financial basis. Investors who think the world is likely to reduce its reliance on fossil fuels and transition to cleaner sources of energy are considering the risk that reserves of coal and oil would be “stranded”. These assets would then be less valuable to their owners.

In Australia, a number of investors are starting to act in response to this risk. Locally, a handful of industry funds have announced restrictions on their fossil fuel investments.

In September last year, Local Government Super announced it would not invest in companies that derive one third or more of their revenues from high-carbon activities. The group, which has funds under management of around $9 billion, sold some Australian pure-play coal stocks such as Whitehaven Coal and New Hope, as well as AGL. The fund kept its shares in BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto, which came under its threshold, but plans to reassess BHP and its spin-off South32 after the recent demerger.

Local Government Super CEO Peter Lambert says the move recognises that any government attempts to mitigate the impact of climate change will focus on carbon emissions, particularly from coal. His fund takes the view that future demand for coal will change dramatically from what coal companies had envisaged. “We're already seeing that with countries such as China moving away from coal into nuclear and renewables,” he says.

“This is definitely a long-term position. No-one will ring a bell until these policies are about to start having a significant impact and if you are waiting for that you run the risk of being the last in line and losing significant value.”

Another industry fund that has made a commitment is health and community services fund HESTA, with $30 billion in assets. HESTA last year said it would not provide funding via rights issues or share placements to listed companies seeking to expand their thermal coal production or exploration. The fund also said it would not make new investments in unlisted companies, or invest in newly listed companies, that derive more than 15 per cent of revenue from these activities. The fund says its policy focuses on new or newly expanded coal production.

Meanwhile, UniSuper excluded companies involved in fossil fuel exploration and production from its two “socially responsible” options, which are around $2 billion in size in total, and make up around 4 per cent of UniSuper's funds under management. And AMP Capital excluded companies from its “responsible investment” funds (which manage $3 billion) that have a more than 20 per cent exposure to mining thermal coal, exploration and development of oil sands, brown coal coal-fired power generation and related activities.

Some “ethical” funds restrict fossil fuel holdings. Also, a number of DIY super funds and philanthropic foundations with more than $500 million under management in total have joined an Australian group called Divest Fossil Fuels, pledging to divest from all direct investments in fossil fuels. And Sydney University has pledged to reduce the carbon footprint of its listed share portfolio by 20 per cent over three years.

What could happen next

Of course, these are just the super funds that have made public announcements about their approach to carbon risk. Nathan Fabian, CEO of the Investor Group on Climate Change (IGCC), an industry association for institutional investors in Australia and New Zealand with total funds under management of around $1 trillion, says this list is not comprehensive. “There are others that are reducing holdings of stock but haven't made public announcements,” Fabian says. “Investors don't normally disclose all their buy-sell decisions, they just make sensible investment decisions. In most cases they'll do the same in this area. They don't need to advertise, they just need to position their portfolio in the best interest of beneficiaries.”

The list of investors that are thinking about the issue is even longer, he says. “Every institutional investor is reviewing their exposure or holdings of emission-intensive and fossil fuel stocks and trying to understand how their holdings should change over time.”

Members sign up to the IGCC on the basis that they acknowledge the financial risks and opportunities associated with climate change and are acting to protect their individual investors. Members include AustralianSuper, BlackRock, BT, Cbus, Colonial First State, Mercer, Perpetual, Russell, UBS and the Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia. Similar associations exist in Europe, the US and Asia, and they have formed a loose global coalition, the Investor Platform for Climate Actions, covering $US25 trillion.

As action in this area expands, locally listed coal companies – led by Whitehaven and New Hope – are struggling on several fronts, with prices falling and public opposition growing louder.

Private investors who are still holding pure play coal companies have “probably already missed the boat”, Fabian says. “It's not to say gas companies and some oil companies won't perform well. It's not to say there won't be coal sold, but the level of debt in the industry, its revenue prospects and the falling demand profile globally puts all those companies in a different position.”

What should an investor do?

A report this year from asset consultant Towers Watson says institutional investors have been asking them whether to continue to invest in fossil fuels. The report recaps the “stranded assets” argument advanced by think tank the Carbon Tracker Initiative and popularised by activists such as 350.org's Bill McKibben: In order to limit the extent of global warming below dangerous levels, only one-fifth of proven fossil fuel reserves can be burnt. This would mean other assets owned by listed companies would be left in the ground, or “stranded”.

“This disparity does not appear to be fully factored in by markets and thus current valuations of fossil fuel companies may be incorrect,” Towers Watson says. “Testing whether the market is fairly priced is never an exact science but the magnitude of this disparity would suggest the risk of mispricing of fossil fuel assets does exist… We believe it is in the interest of investors with medium to long-term investment horizons to explore the stranded assets argument in the context of their own portfolios.”

Australian Conservation Foundation energy analyst Tristan Knowles says possible approaches for private investors could include completely divesting from fossil fuels, excluding stocks that have a 100 per cent revenue exposure to fossil fuels or tracking and reducing carbon intensity across a portfolio. “Prudent investors say if there is a risk, you're not being a responsible investor if you're not taking this seriously,” he says.

Meanwhile, Goldman Sachs research as early as 2013 warned of a darkening outlook for thermal coal. “The window to invest profitably in new mining capacity is closing,” wrote analyst Christian Lelong. “Earning a return on incremental investment in thermal coal mining and infrastructure capacity is becoming increasingly difficult.” The report said the threat to coal's dominance as a fuel was structural, due to three factors: “environmental regulations that discourage coal-fired generation, strong competition from gas and renewable energy and improvements in energy efficiency”. Diversified miners are reallocating capital to more attractive sectors in response, the report said.

Julian Poulter, CEO of non-profit the Asset Owners Disclosure Project, believes a repricing of climate risk is most likely within the time frame of the next seven to 15 years, causing “major trouble” for carbon-intensive stocks. Investors who are 65 now might look at the historical returns from some fossil fuel companies, or other heavy carbon users such as manufacturing and transport companies, and want to hold on to them. “With an average age into their early 80s, you'll find well before the end of their lives the climate issue will have blown up,” Poulter says.

AMP Capital head of investment strategy and chief economist Shane Oliver takes the view that although considering environmental, social and governance factors will help enhance investment returns over time, coal faces a separate headwind in the form of cheaper solar power. “Solar and electric technology in cars will end up supplanting carbon related energy sources as solar becomes more efficient. But that has nothing to do with the view that we should avoid coal because it pollutes, it's more that the evolution of solar will make it eventually cheaper than coal,” Oliver says. “Any resource analyst working for a fund manager should pick that up.”