Will the RBA step in to tackle the dollar?

Summary: Adjusted for inflation, the Australian dollar remains much higher than the Reserve Bank would prefer. |

Key take-out: To lower the dollar, the RBA could cut interest rates but the spread between Australian and US government bonds suggests that this might be more dangerous than many realise. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Economics. |

The Reserve Bank of Australia meets next week for the first time this year, following a two-month break, and it has plenty to think about.

Low inflation and a stubbornly high Australia dollar are likely to dominate discussion, while politico-economic concerns abroad may also weigh heavily on the economic narrative.

Benign inflation

The most recent set of inflation figures, released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), continue to set out a fairly benign inflationary environment. Core inflation, which is the average of the trimmed-mean and weighted-median measures that exclude volatile items, rose by 0.4 per cent in the December quarter and has increased by 1.5 per cent over the year.

Core inflation, and headline inflation for that matter, remain well below the RBA's target of 2-3 per cent inflation over the medium-term. Headline inflation has now fallen below that target for nine consecutive quarters: core inflation hasn't reached 2 per cent since December 2015 and remains only a touch above its lowest level since at least the Second World War.

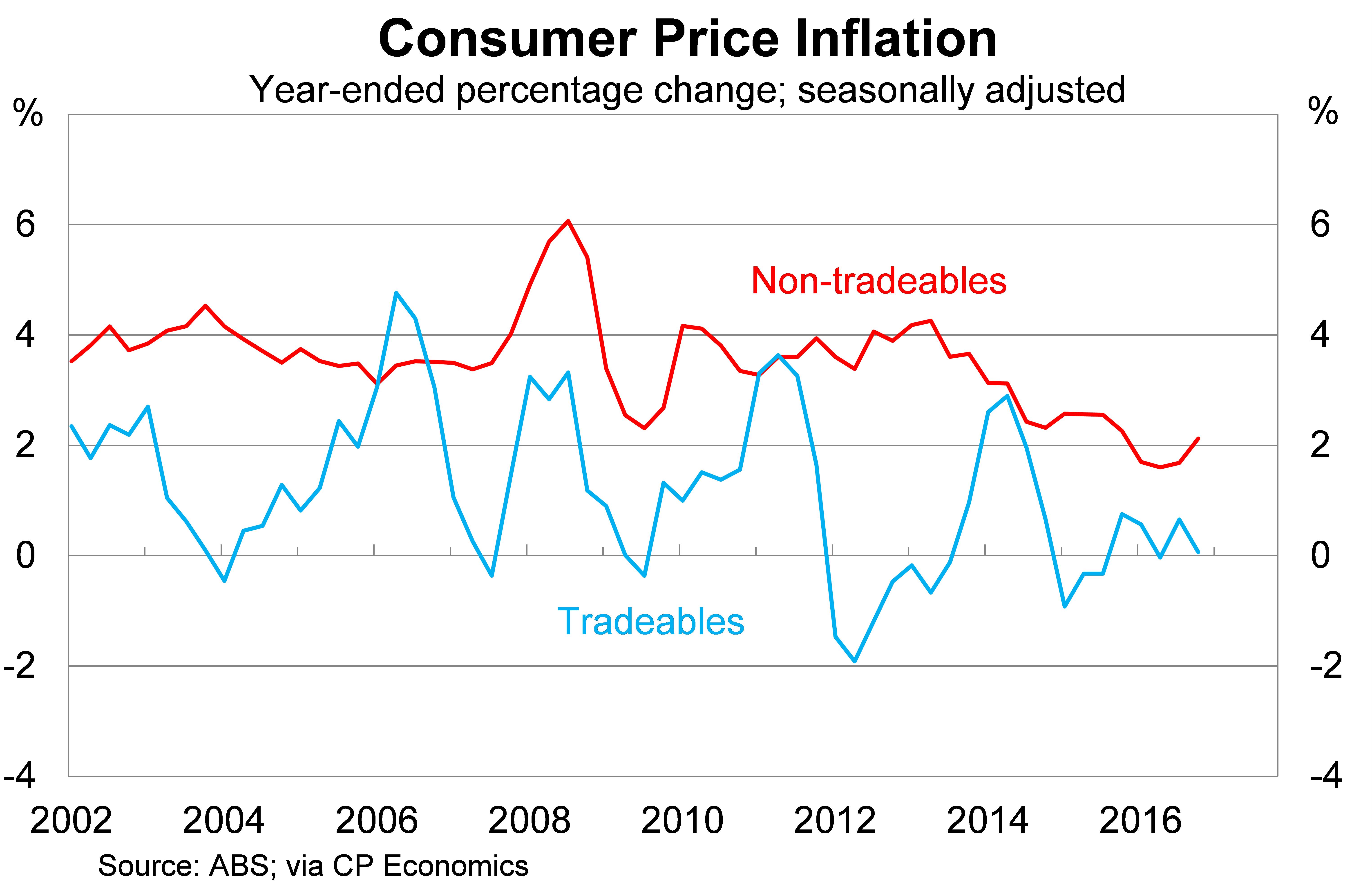

Some good news for the RBA is that inflation on non-tradeable goods – which can be used as a proxy for domestically generated inflation – picked up a little during the December quarter. Inflation on non-tradeable goods rose by 0.9 per cent in the quarter and is now 2.1 per cent higher over the year.

This is still some way off the 3-4 per cent growth for non-tradeables that was considered normal until a few years ago but it is also a lot stronger than the trough of 1.6 per cent established in June 2016. At the very least it suggests that wage growth may begin to pick-up and that can only be a good thing for the broader economy.

But we continue to see little inflation on tradeable goods. This is partly due to low inflation abroad, which is thankfully improving, but also an Australian dollar that remains stubbornly high.

Dizzying dollar

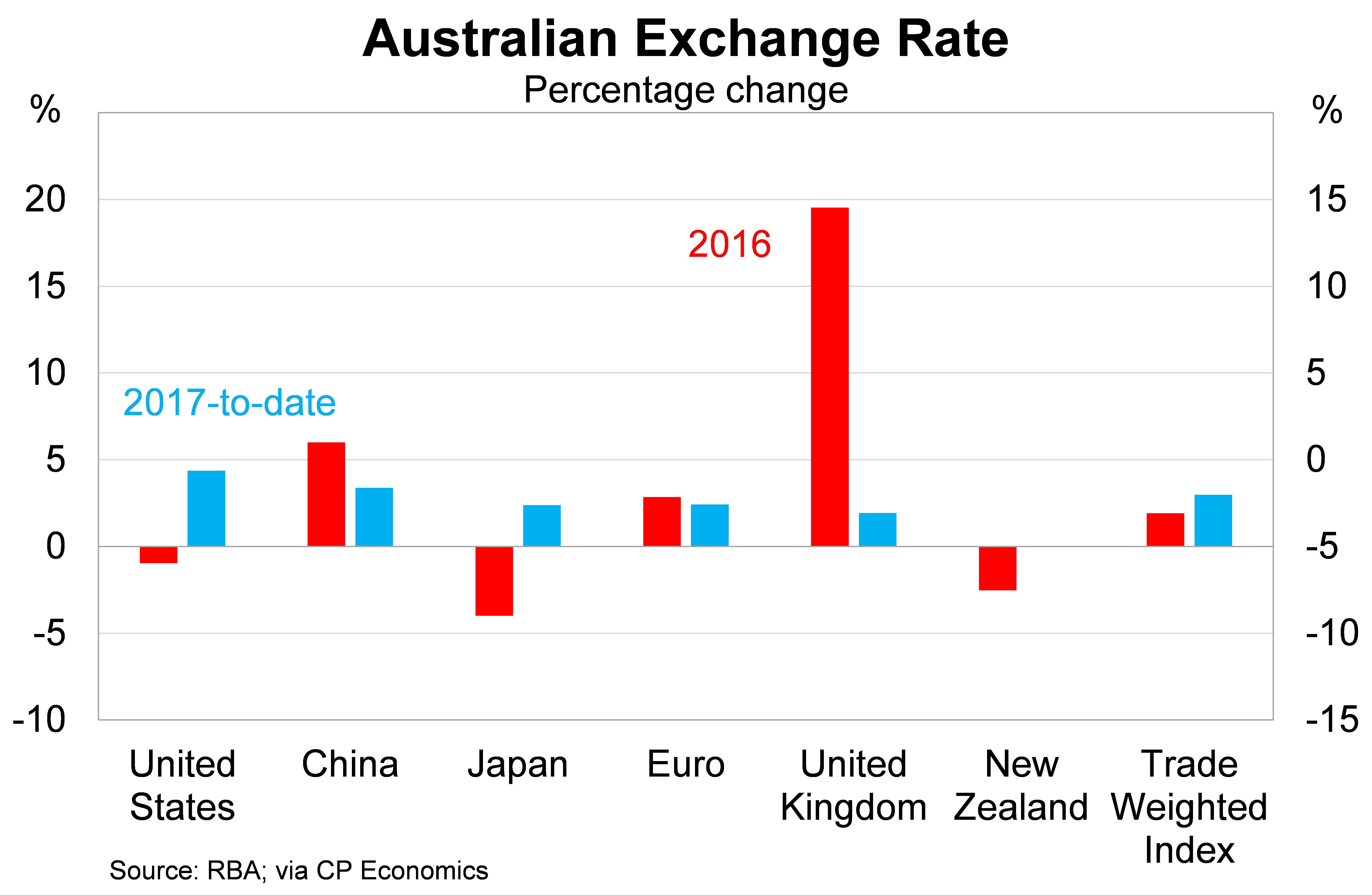

In 2017 so far the Australian dollar has appreciated 4.4 per cent against the US dollar; 3.4 per cent against the Chinese renminbi, and 3 per cent against a trade weighted index of currencies. The graph below shows the percentage change in the Australia dollar compared to our major trading partners during 2016 and 2017.

With the real exchange rate – the standard exchange rate adjusted for inflation – still 14.4 per cent above its long-term average, it is clear that the Australian dollar remains much higher than the RBA would prefer. I see three central reasons why this is the case, which I also discuss on video with Editor Tony Kaye.

First, commodity prices, led by iron ore and coal, have increased throughout 2016 and supported the dollar. Australia has long had a commodity currency and shifts in the price of iron ore and coal directly feed into the value or our currency.

Second, interest rates in Australia continue to exceed rates in the United States and other developed economies. This helps to attract foreign capital to Australia and supports the value of our currency.

Third, Australia maintains a AAA credit rating which makes federal government bonds one of the few remaining AAA rated assets. This makes Australian dollars an attractive investment for fund managers looking to hold high quality assets.

Analysts expect commodity prices to decline throughout 2017 as some of the temporary supply issues that pushed prices higher last year begin to dissipate. Speculative activity in futures markets is also likely to normalise at some point and that should see commodity prices return to a level that is more consistent with underlying demand and supply.

Higher commodity prices are supporting mining revenue and profitability and has given Australia its first trade surplus since early 2014. Nevertheless, it's far from ideal for the non-mining sector and creates a significant challenge for that sector as it tries to rebound from what has been a relatively tough decade.

The RBA's options

The RBA has few tools with which it can lower the value of the Australian dollar. ‘Jawboning' has been one technique, where bank officials take down the dollar in an attempt to shift market sentiment, but it has proven ineffective in the past.

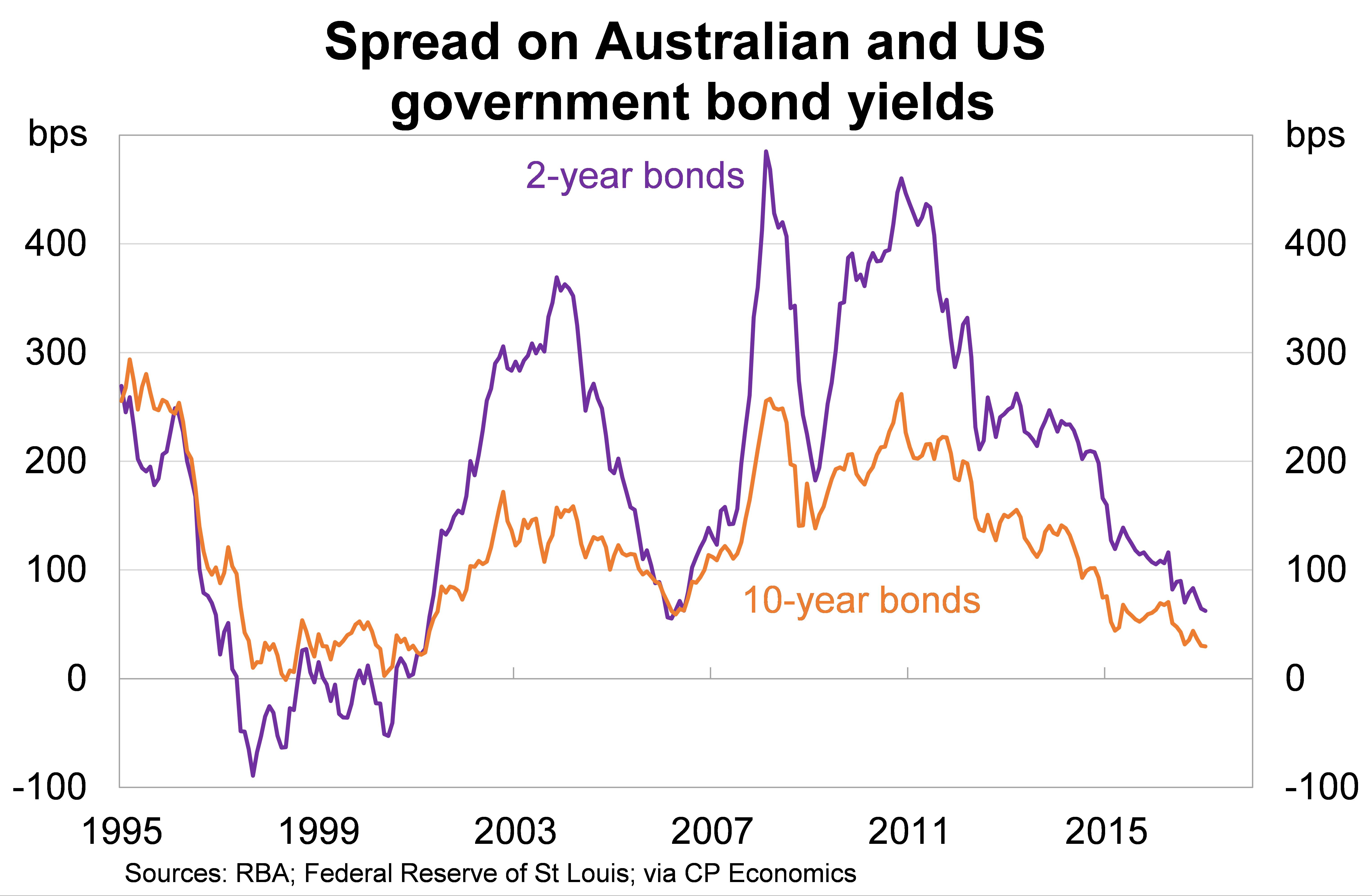

Another technique is that the bank can simply cut interest rates further but the tightening spread between Australian and US government bonds suggests that this might be more dangerous than many realise.

The graph below shows the spread between Australian and US federal government bond yields. It includes one short-term bond, the two-year rate, and a longer-term bond, the 10-year rate.

The spread on two-year government bonds currently sits at around 62 basis points; by comparison, the spread on 10-year government bonds sits at 30 basis points. The former is at its lowest level in 10 years, while the latter hasn't been this low since early 2001.

Given the likelihood that the US Federal Reserve hikes rates this year – possibly on two or three occasions – there is a very real chance that the spread turns negative.

Many will remember that the period from 1997 to 2000, when the spread was last negative, coincided with the Australian dollar falling below US50c. I wouldn't expect that to occur this time but I also wouldn't be surprised if we tested US60c either.

Historically Australia has always needed an interest rate premium to attract foreign capital and a negative interest rate spread against the US raises the question: why invest in Australia when there are greater returns to be found in the US?

Australia runs a sizable current account deficit, which means that we rely on foreign capital to drive investment and maintain existing growth. A negative spread suggests that some Australian investors may choose to invest overseas rather than doing so domestically.

It would take a bold central bank to cut interest rates in such a scenario but if the RBA does then it will certainly get more bang for its buck on the currency side than it has in the past. The key question is whether it is willing to risk capital flight and a decline in our current account deficit?

A key question for the RBA is whether the recent sell-off in US government bonds is temporary or persistent. In other words, will Donald Trump make good on his fiscal and tax policies? If the answer is no, then the RBA has more scope to cut rates. But if Trump delivers, then monetary policy in Australia is largely exhausted.

However, regardless of whether the RBA cuts further it appears as though the Australian dollar is reaching a tipping point. A lot will depend on commodity prices, but narrowing spreads and the likely end of Australia's AAA credit rating will put downward pressure on the dollar. If commodity prices shift downwards, as analysts expect, then the dollar could very quickly end up below US70c and fall to levels that we haven't seen in well over a decade.