Why markets are stirred, not shaken, by Congress

We have seen significant volatility and uncertainty in Washington, DC, over the last month: The federal government shutdown on October 1, a leading contender for the Federal Reserve chairman position, Larry Summers, took himself out of consideration, and the Fed surprised markets by deciding to hold off on tapering its asset purchase program, citing congressional dysfunction as one of its reasons. And a debt ceiling increase looks like it might be taken hostage once again.

Aside from expressing fatigue with the brinksmanship in Washington, investors are also asking what to make of the current situation in DC – and importantly what it means for portfolios.

The government shutdown: How did we get here?

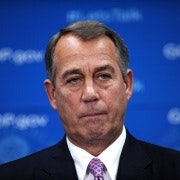

We were generally expecting that Congress would pass a government funding bill void of policy riders at the last minute to avert a government shutdown. Why? After all, not only had Republicans and Democrats passed “clean” funding bills in the past with little consternation (as recently as March 2013), but Speaker John Boehner had the votes to pass a clean government funding bill this time – all he needed was to bring it to the floor for a vote.

So, why did Speaker Boehner not bring up that bill? We believe it is simply because of politics within the House Republican conference. In January, in order to pass the fiscal cliff compromise, Speaker Boehner had to rely heavily on Democrats because the majority of Republicans did not believe it was a good deal for them; this defied the internal Republican 'Hastert rule', which states that any bill brought by House Republican leadership should receive the “majority of the Republican majority”.

Largely after this incident (and other votes such as funding for Hurricane Sandy where he also defied the Hastert rule), Boehner – and his speakership – has effectively been on probation within the Republican caucus. If he had brought up a clean government funding bill with no policy riders targeting the Affordable Care Act ('Obamacare'), it would have passed – but only with a majority of Democratic votes and a handful of Republican votes. So while the government would not have shut down, Boehner’s speakership would have been at great risk.

How bad is a shutdown?

The government has shut down a total of 17 times before, with the longest shutdown occurring during the last episode in 1996, which lasted for 21 days. During that shutdown, GDP growth declined by 0.3 per cent annualised in the quarter the shutdown occurred, but improved significantly the following quarter as furloughed employees received the back pay owed to them. We would not be surprised if growth feels a similar impact this time – approximately 0.1 per cent to 0.2 per cent of GDP (annualised) in the fourth quarter for every week of a shutdown; however a bill to back pay furloughed workers, as happened in 1996, has yet to pass through the Senate.

While the growth impact – assuming a relatively short shutdown – is small in the grand scheme of things, the economy is also still grappling with approximately 1.7 per cent of fiscal drag associated with the fiscal cliff and sequester, so a shutdown represents yet another self-inflicted wound to already modest growth.

The debt ceiling is more worrisome

While the fiscal drag associated with a shutdown should be relatively manageable, what is more disconcerting is what it means for the upcoming debt ceiling, which, according to Secretary of the Treasury Jack Lew, will have to be raised by October 17. Many are understandably worried that if lawmakers are willing to take a short-term funding bill hostage to the point of shutdown, why would they not take us over the edge: refusing to raise the debt ceiling in order to advance their goals.

While we understand this logic, we do not think this is the way the next few weeks will play out. We think that while Speaker Boehner refused to bring up a vote that defied the Hastert rule for the government shutdown, he would cut a deal with Democrats in order to stave off a default on US sovereign debt, even if it risked his speakership (which is likely on somewhat more solid ground now that he helped to shut down the government). After all, Boehner is not interested in letting his overarching legacy be a government default, throwing the financial system into disarray and dealing what could potentially be a catastrophic blow to the economy.

Debt ceiling and government funding bill will likely be addressed in one package

We expect both sides to back off their rhetoric and come to the negotiating table – but not before they absolutely have to. This likely means that we should expect the government shutdown to last weeks, not days, right up until the October 17 debt ceiling deadline.

In terms of a potential deal, it is unlikely that Republicans will get any real concession on “Obamacare,” as President Obama is unlikely to sign anything into law that undermines his greatest legislative achievement. However, Republicans could get a provision or two that provide sufficient political capital, such as a repeal of the medical device tax and indexing of Social Security benefits using chained CPI (the Consumer Price Index of inflation). Democrats would also insist on something for these concessions: a year increase of the debt ceiling, funding the government through the end of the fiscal year and maybe even a deal on the sequester (which both sides hate, but Democrats hate more).

Market impact of the debt ceiling debate: It probably will not matter, but look out if it does

In short, while the market seems to be mostly sanguine about the government shutdown, a breach of the debt ceiling – which we feel is highly unlikely – would be incredibly negative for financial markets.

Fundamentally speaking, if the US government defaults on its obligations (Treasury securities or other), any asset with a dollar sign ($) in front of it is immediately weakened. However, markets will not react meaningfully until the very last moment.

Sadly, markets have come to expect (and accept) dysfunction from Washington. The strong equity market performance this Tuesday (October 1), in the first trading day following a government shutdown, tells the story: Markets have built up an incredibly strong immune system to defend against most wounds the government can inflict. Investors and business leaders expect uncertainty regarding the government’s policies on spending and taxation; they expect partisan politics and brinkmanship; and they expect no compromise to happen until right before or shortly after any deadline for compromise (see the January 1, 2013 fiscal cliff resolution). Since we forecast a similar eleventh-hour deal this time around, markets will likely not have to grapple with the “what if.”

But what if?

We thankfully lack market experience in situations where the world’s largest bond issuer, which also presides over the world’s reserve currency and currency of choice for denomination of the majority of the globe’s financial transactions, decides to willingly default. However, we believe it is safe to say that a US sovereign default would be extremely negative for US (and by contagion) global equity markets. The 13 per cent decline in US equities in the first week of August 2011, in the aftermath of the last near-default and subsequent ratings agency downgrade, provides some frame of reference. Credit markets would likely suffer materially, if not catastrophically, as well.

Perversely, the likely impact of a sovereign default on US Treasuries to US Treasuries, themselves, is more ambiguous. Certainly a default event would frighten, confuse and unnerve a large group of Treasury market investors – and at PIMCO we would re-evaluate our Treasury portfolio positioning. However, a default event is an extraordinarily damaging event to not just the Treasury, but all of “USA Inc.” And while many assets would certainly flee, some investors beholden to dollar-denominated assets may decide to move up in the capital structure of USA Inc. – shedding equities in favour of sovereign debt securities. Their line of thinking would be that default will lead to deeply negative growth, declining equity markets, and therefore ultimate realisation from Congress that perhaps this was a mistake – and that Congress should, in fact, pay its obligations. This would mean Treasuries (particularly the front end of the yield curve) could expect to see new demand, much like they did in the aftermath of the August 2011 rating downgrade.