Why investors are buying the banks

Summary: Many investors may be questioning whether they should sell bank shares given the market's sentiment that valuations have become too stretched. Before they do, however, they need to keep in mind a fundamental difference that has developed in the investment landscape: With interest rates at record lows, the reliability of bank yields of between 6.5 per cent and 7.5 per cent remains attractive compared to the broader market. |

Key take-out: The banks become a “sell”, in an ultra-low rate world, when earnings are under threat to the point that dividends may no longer be stable. According to data provided by Iress, this has only happened once in the past 20 years – during the GFC. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Economics and Investment Strategy. |

The big question for investors is this: At what point should you actually consider selling the banks?

It's a problem compounded by the fact that with ultra-low interest rates, the subject of valuation becomes much more difficult.

What investors have learned is that ultra-low rates have changed the investment landscape. The analysis is no longer as simple at looking at the banks, stating that they're expensive and then slapping a sell on them; although we still obviously have to pay attention to valuations, models must be augmented to reflect the fact that the discount rate is much lower now.

Valuations that may have looked expensive before the GFC may no longer be in this new world we find ourselves in. Based on traditional metrics, many asset classes – many stocks – are already expensive. And yet investors still drive prices higher.

Noting this, it makes more sense analytically to have a think about why investors are prepared to pay for apparently expensive stocks like the banks – and then look at some of the issues surrounding that.

Banks as a yield play

In an ultra-low rate world, yield is obviously a key reason why the banks are so popular. We all know that.

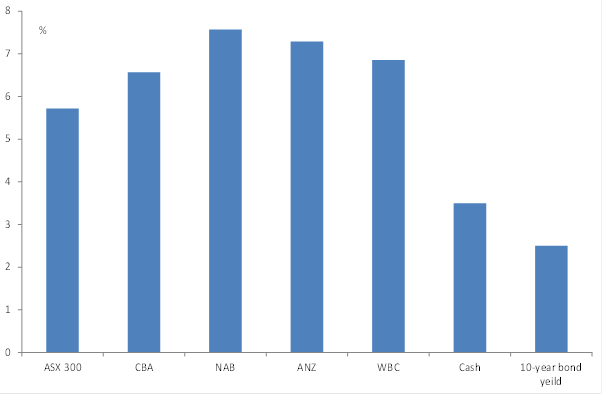

We also know that this yield is still very attractive; notwithstanding capital gains ranging from 22-37 per cent over the last two years, the big banks still have a dividend yield of between 6.5 per cent to 7.5 per cent grossed up. This compares to cash at around 3.5 per cent, the 10-year bond yield at 2.5 per cent and the broader S&P/ASX300 at 5.6 per cent (grossed up).

Chart 1: bank dividend yields remain attractive

It makes sense that this is the first place we should start when thinking about whether we should sell a stock. Let's take the example of where the dividend yield on the banks approaches that of the broader market.

To get to that point (i.e. a 5.6 per cent grossed up yield), and assuming no change in dividends (which I'll get to below) means that bank stocks would have to rally something like 15 per cent to 32 per cent from today's prices. Yet, even at that point, a 5.5 per cent grossed up yield is still attractive.

In the more likely scenario that dividends grow in line with earnings (so a stable payout ratio), then the banks could rally a further 24 per cent to 40 per cent before their dividend yield fell materially below the market.

Now you can imagine that if the banks shoot up by anywhere near those magnitudes, then there would be strong calls put “sell” on the banks. Yet what does an investor do? Bank yields in the worst-case scenario would still be competitive with the rest of the market and much higher than anything available in cash or bonds – and that's only after a 24-40% capital gain.

Admittedly, they would cease to be high-yield stocks, but then again they're not currently the highest dividend yielding stocks in the market anyways. Clearly not all yields are equal, with a handful in the S&P/ASX 200 that have dividend yields up to 30 per cent or so. But would you buy them? No, probably not, because there is no saying that you'll get that yield next year.

What sets the banks apart is the reliability and stability of their dividend. Indeed, a strong argument could even be mounted that banks would still be attractive paying below-market dividend yields.

Why? Because of their strong history of paying stable – and growing – dividends. This has value in a low interest rate world – as a kind of proxy for cash. Thought of another way, the dividend a bank pays is AAA – it's safe. So if banks are increasingly traded as a yield play, then it's reasonable to expect (on a risk/reward basis) that their dividend yield should be lower than the rest of the market given it is a more secure investment.

In an ultra-low rate world, there are some investments where the key question changes. It changes from whether earnings justify valuations, to whether earnings are sufficient to support a decent and stable dividend yield not too far from the market (adjusting for risk). It doesn't even have to be above the market yield, as long as what is paid is more stable and more reliable than elsewhere.

All this highlights an important point. Few investors would hold the banks based solely on their current dividend yield. Dividends are not guaranteed and so most investors would hold them for their growth potential as well. That is, revenue and earnings growth. If an investor doesn't hold a high degree of confidence in a bank's capacity to maintain the revenue stream, then they are just gambling.

Logically enough, strong investor interest in our banks reflects a vote of confidence in their capacity to earn and to continue paying that dividend – and rightfully so, as news so far has been very good.

Indeed, bank earnings to date have been robust. While ANZ issued a disappointing trading update earlier this week, the result was only for one quarter. Moreover, the earnings underlying must have been solid given the acceleration in loans that ANZ reported (up 8 per cent).

And this is what it really comes down to for the banks. Can they grow their lending books in a safe and reliable fashion? The answer is unequivocally yes. Credit growth has accelerated sharply, sure, but it is still well below average growth rates at a time when corporate leverage is low (on average) and household debt servicing is at a decade low.

There are no visible headwinds at this stage to further strong credit growth. On top of that, bad debts are low and regulators are satisfied with capital provisioning.

With that in mind, Australia's banks may not become a “sell” for yield-hungry investors after they've breached some valuation level or after yields have compressed to the market.

The point at which the banks become a “sell” (in an ultra-low rate world) is where earnings are sufficiently under threat that dividend stability comes under question. According to data provided by Iress, this has really only happened once in the last 20 years, and you won't be surprised to learn that it was during the GFC. Otherwise, Australia's banks are likely to remain a high demand investment.