'Whatever it takes' is not the whole story

After fighting the weakness of its euro currency for the past five years, the European Central Bank now seemingly has an even more fearsome opponent to tackle: the strength of the euro. At least this is the narrative that the ECB is trying to establish.

The new narrative goes something like this: Thanks to ECB President Mario Draghi’s promise to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro, confidence in monetary union has returned. The unfortunate side effect of this cure has been an appreciation of the euro in international markets. This in turn, however, has reduced import prices, damaged the competitiveness of European economies and has created deflationary pressures in Europe. Therefore, fighting deflation and talking down the real strength of the euro now go hand in hand for the ECB.

Whether you accept the ECB’s story of the super-strong euro leading to deflation or not, the real story is a little more complicated still. That is because we are still not dealing with just one euro but with as many euros as there are eurozone members. Even 15 years after the euro’s introduction, their economies remain disparate and their monetary needs diverse. Whether the euro needs to depreciate against other major currencies depends entirely on the respective national viewpoint.

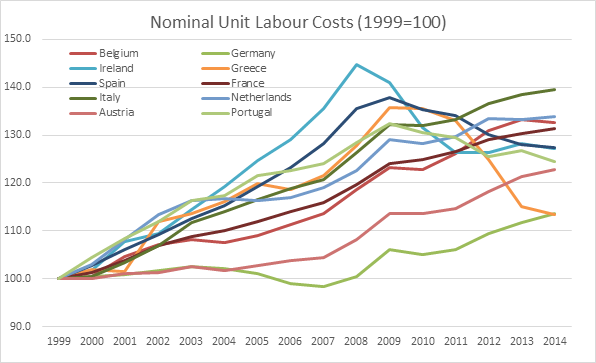

There are calculations that tell the story in a nutshell. The first is the time series on nominal unit labour costs, or technically speaking the ratio of compensation per employee to real GDP per person employed. The European Commission provides these data in its annual macro-economic database (AMECO). It is well worth studying because it shows quite clearly why the euro crisis is not over yet.

The first thing that stands out from the graph is that from the introduction of the euro until the start of the euro crisis, unit labour costs relative to productivity had been stagnant in Germany (meaning that wage increases had matched productivity increases) but had risen in the other members of the eurozone. This was actually one of the core problems of the eurozone – and a trigger for the crisis. Through its policy of wage restraint and productivity increases, Germany had outcompeted its neighbours, while other European countries gradually lost their competitiveness.

What we have seen since the start of the crisis is an attempt to rebalance the eurozone. On the one hand this means that periphery countries have to become more competitive, i.e. cheaper. On the other, Germany could aid this process by becoming more expensive. The graph below shows that a little of both has happened – but not nearly enough to bring Europe much closer together.

Despite some increases in unit labour costs in recent years, Germany still remains the eurozone economy with the lowest increases in unit costs since 1999. The crisis countries -- Spain, Greece, Ireland and Portugal -- have managed to regain some ground vis-à-vis Germany. However, no such progress has been achieved in other countries. France, Italy, Belgium and the Netherlands have not managed to diminish their unit labour costs and remain less competitive compared to Germany than they were in 1999.

Unfortunately, this graph does not tell the full story either. It is well possible that some of the improvements in unit labour costs in the periphery have been achieved at the expense of rapidly rising unemployment rates. Note that the denominator of this index figure is “per person employed”. As companies went out of business in these countries, it would have to be assumed that the least productive companies went first. This means that only more productive companies survived the downturn. This may have left lower unit labour costs behind but also higher unemployment. As an aside, Germany’s rising unit labour costs could also be the result of declining German unemployment over the same period.

Given this background, one might well argue that the great divergence between German and non-German unit labour costs continues to burden the eurozone, and even those improvements we seem to see are only a statistical fluke but not a sign of real economic recovery.

The great discrepancy in unit labour costs then also means that some countries still need to become relatively cheaper (i.e. more productive) in order to become competitive. In order to achieve this without leading to outright deflation in the crisis countries, it would require Germany to accept higher inflation rates. There is no sign that the Germans would be willing to accept this.

The second calculation showing how diverse the eurozone remains, comes from Morgan Stanley. Last month, its research department calculated what the euro’s exchange rate would have to be based on eurozone members’ competitiveness. These were the results:

As the euro is currently trading at around $US1.38, this makes it too soft for Germany, just about right for Ireland and Austria – and too hard for every other member of the eurozone. So a depreciation of the euro, even if Mario Draghi could bring it about by talking his currency down, would only serve solve some problems but exacerbate others.

This, then, is the ECB’s main problem. It is not the supposed “strength” of the euro but its remaining diversity. Fifteen years after the start of the euro project, and more than five years after the beginning of its visible crisis, the countries bound together by the euro have not become more similar but are growing further apart. It is practically impossible to implement any monetary policy that would do justice to circumstances in all of its member countries.

What may look like the euro’s strength is not quite what it seems. The eurozone remains as fragmented as ever, and neither Draghi’s words nor any real actions of his central bank will make a difference to this basic problem. The only way to tackle it would be a departure of some members from monetary union.

Dr Oliver Marc Hartwich is the Executive Director of The New Zealand Initiative.