We need more migrants in a crisis, not less

This week’s unemployment data caused quite a stir, with some observers making a hasty link between the number of Australians joining the jobless queues, and the number of migrants still pouring into the country.

Monash demographer Bob Birrell led the charge, arguing in the Fairfax press that “... the number of overseas-born persons aged 15 plus in Australia, who arrived since the beginning of 2011, was around 709,000. Most of these people are job hungry.

“According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics Labour Force Survey, 380,000 of these recent arrivals were employed as of May 2014. Over the same three years, the net growth in jobs in Australia is estimated by the ABS to have been only 400,000.

“This means that these recent overseas-born arrivals have taken almost all of the net growth in jobs over this period. They are doing so at the expense of Australian-born and overseas-born residents who arrived in Australia before 2011.”

Yikes. Pull up the drawbridge. Sound the alarms.

Well not quite. Drawing a direct link between migration and jobless numbers is far more problematic than that.

The motivation for Birrell’s line of attack is clear, and quite worthy – namely that we have a youth unemployment crisis, and an under-employment crisis more generally, with welfare benefits putting an increasing burden on the federal budget.

All quite true. All very alarming.

However the matching up of the jobless numbers with the immigration numbers paints a false picture.

More importantly, this kind of assertion can easily be mis-used by populist political forces to stir unrest in the community and unfairly paint migrants as a burden on the economy when they are nothing of the kind.

The logical disconnect is found when one considers what kinds of job openings exist, where they are located and the willingness of ‘pre-2011’ Australians (to use Birrell’s distinction) to take them.

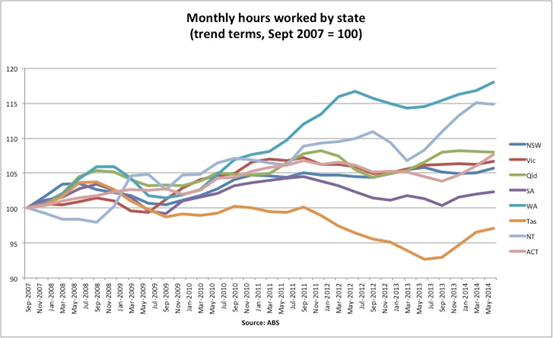

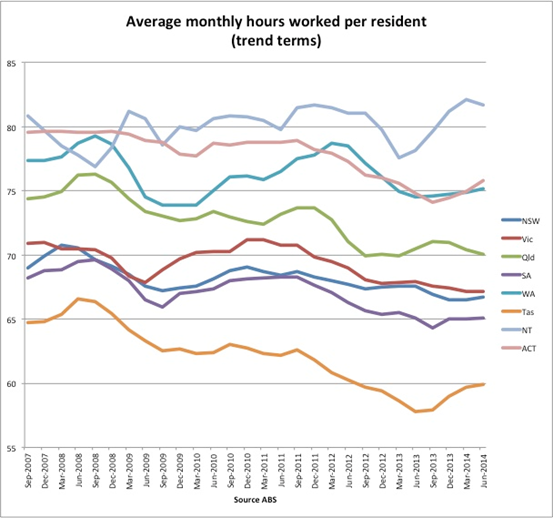

The two charts below reveal a lot about the distribution of work around the country, and the trends in the amount of work available overall since the beginning of phase one of the GFC in late 2007. (Note that the final two quarters of the second chart rely on population estimates, as the ABS has not yet published March and June 2014 figures).

The first chart shows only how the gross number of hours worked in each state has grown in the past seven years. WA seems to be romping along, just ahead of the NT, with both being well ahead of the clustered Queensland, Victoria and NSW.

However, this picture is misleading, as it does not capture population movements. WA’s population, for instance, has grown an astonishing 21 per cent in seven years, which means its nation-beating growth in hours worked is spread across a population that is 445,000 people larger.

The second chart, therefore, shows how the number of hours of work available averages out over a state’s population. Tasmania, as will surprise few, has a far lower number of hours worked per resident each month (60 hours) compared with WA (82 hours).

That’s not surprising as WA is still enjoying the jobs created by the construction phase of the resources boom (though that will moderate in the months and years ahead).

Most interesting, however, is what Tasmania was doing just three years ago when its average hours worked per resident was continuing to slide -- from about 65 hours at the start of the GFC to 62.5 hours in April 2011.

Even without taking population movements into account, the total monthly hours worked figure (see first chart) showed no increase through the four years of GFC.

So what was the Tasmanian government doing at that time? It was, in fact, running roadshows around recession-ravaged Ireland, hoping to recruit a range of skilled workers to start a new life in the Apple Isle.

As Business Spectator reported at the time, Tasmania was looking for workers in "medical and allied health, engineering, hospitality, urban and regional planning, agricultural science and metal fabrication and trades such as automotive mechanics, plumbing and electrical".

Were they mad? Surely they could have recruited thousands of such workers from Melbourne, Sydney or Perth?

Actually, no.

Angela Chan, national president of the Migration Institute of Australia, says that’s just not true. Employers in regional and remote Australia find it extremely difficult to fill positions with workers who have families, homes and lives in our capital cities -- cities that house the unusually high figure of 85 per cent of our population.

MIA is the umbrella group for migration agents in Australia, so there is an element of "they would say that wouldn’t they" -- especially as Scott Morrison begins investigations into how migration visas have been misused or rorted in the past few years.

However, the explanation Chan gives gels exactly with stories many regionally-based MPs have told this columnist over the years: it is sometimes easier to employ Korean workers or recently arrived refugees in Alice Springs hospitality jobs than Australians. Or to employ Iraqis to pick fruit in Shepparton, for instance.

The allure of such roles for established Australians is just not there -- as evidenced by the Gillard government’s rather fruitless attempts to coax youngsters out of capital cities with bonuses and relocation payments.

What makes a direct link of migration and jobless numbers most worrying, according to Chan, is that towns that don’t have medical staff, accountants, engineers or other skilled workers are hobbled economically -- the businesses that would otherwise employ the low-skilled, or even many other classes of skilled workers, don’t get going.

Viewed in this context, it can be argued both that we have a huge unemployment problem to solve, and that it will only be made worse by choking off skilled migrants who are just as prepared to set up house in Bendigo or Mount Gambier as Melbourne or Adelaide.

That is not to argue that all skilled migrants are wanted or needed -- just that there are good reasons to keep the flow higher than many would assume in hard times (An awkward time to mention migration, July 8).

The government will have a hard time explaining that to voters, however, as the body set up to advise on such subtleties, the Australian Workforce and Productivity Agency, was one of the first agencies it scrapped on coming to power.

But there is a lot more to the migration-jobs nexus than meets the eye.