Treasury boffins need a science lesson

The Commission of Audit was set up to outline how the Coalition government could get the budget back in the black but its recommendations on education, particularly the implications for science and technology research, potentially spell doom for Australia’s future prosperity.

The report’s recommendation that CSIRO’s independence be curtailed “to ensure that resources are being directed at areas of greatest priority” follows recent speculation that the nation’s peak science research body -- which brought to the world such marvels as Wi-Fi and the black box -- could see its funding slashed by more than 20 per cent in the coming federal budget.

Meanwhile, ICT-focused NICTA’s future is also in doubt after the Coalition government vowed to end $42 million worth of federal government funding promised under Labor. Significant cuts to the research body from the Victorian government earlier this year have already impacted the institution, which sacked half its staff in the state as a result.

Wealth vs Revenue

Governments are entitled to getting the most bang for their buck for their investment but the problem lies in how that return is measured, and if we are talking about “areas of greatest priority”, preferencing tangible outputs like revenue may come at the expense of longer-term economic benefits.

NICTA chief executive Hugh Durrant-Whyte says research organisations are about generating wealth as opposed to revenue, but unfortunately that argument holds little sway with the boffins at Treasury.

Durrant-Whyte adds wealth isn’t just about the dollars that get through the door but is about the impact on a country. Wealth can be measured in tangibles, he says, but there is just as much onus on institutions to better communicate these achievements as there is for the “pointy heads” in Treasury to understand them.

“If I save the government $1 billion by not building a piece of infrastructure because of a technological advance, I’m not actually generating revenue, I’m creating wealth,” he says.

“If I save a company $100 million I ought to be able to measure that, and if I take a group of people in my organisation that are generating revenue and spin them out as new company then I lose the revenue but I’m creating wealth for the company.”

Rethinking how we evaluate the effectiveness of investment in science and technology also applies to our universities and Durrant-Whyte adds that institutions need to get better at explaining the value of what they do.

“It’s as much my fault as anyone else’s -- if we don’t do that there is no argument for making any investment in deep research.”

It’s the outcomes that matter

Albert Goller, chairman of the Manufacturing Excellence Taskforce Australia, says institutions should be framing the value of R&D in terms of outcomes rather than output.

META -- a joint initiative between industry and researchers (all Australian universities are members) -- is focused on driving future growth in Australian manufacturing and Goller says that an undue focus on outputs, such as publications, paints a false picture.

“An outcome for me would be how many of my students after they leave university got a job in the next 12 months in the area that they studied. That’s an outcome. We are measuring too much on output -- 100 per cent of students have left and we tick it off. But if 50 per cent can’t get a job that’s not a valuable outcome.”

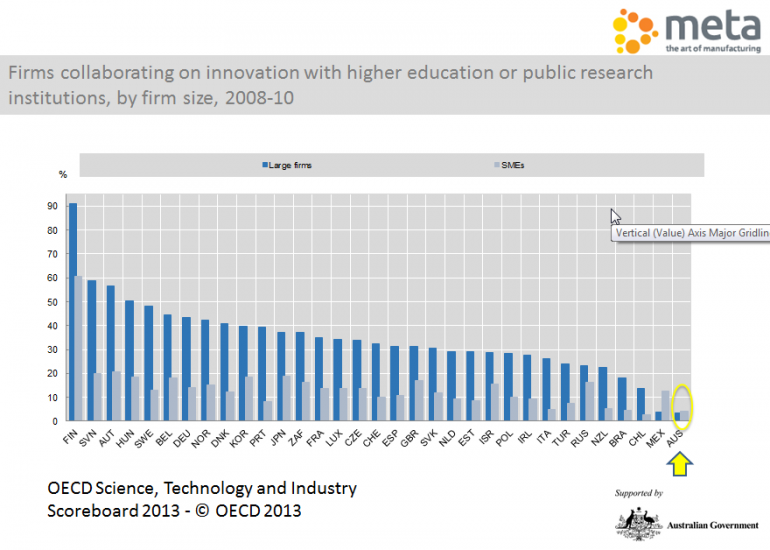

One of the ways to improve outcomes like these is to increase institutions’ collaboration with industry. Australia ranks last in the entire OECD group of nations in terms of collaboration between research organisations and business.

It’s a worrying statistic, but on the flipside it’s also a vast opportunity for wealth creation at Australia’s fingertips.

“I see this in universities and I see it in every single student -- we want to get access to their heads and use that for helping industry,” says Goller.

“At META we have 25 students working for us on a permanent basis. It’s refreshing what kind of ideas they’re coming up with and we learn as much as they do.”

Again, says Goller, the value of R&D -- whether it be within companies or in collaboration with research organisations -- should be measured in terms of outcome rather than in terms of output or the amount of dollars put into the research.

“The number of patents is not an outcome, it’s an output. An outcome is how many products can you say in the last 12 months we’ve brought to the market that the base was the research we did in that university? Cochlear wouldn’t be where they are [if they hadn’t had this kind of mindset].”

Of course, this begs the question: if big companies like Cochlear are successfully creating long-term wealth through in-house R&D activity, why do we need the public research bodies?

The reality is that smaller companies simply don’t have the resources to pursue their research ideas. And while the federal government is unlikely to implement all of the measures recommended in the Commission of Audit, amid raucous opposition to the shaving of big-ticket items like healthcare, pensions and access to tertiary education, the scrapping of little-known start-up industry assistance programs such as the Innovation Investment Fund and Commercialisation Australia is likely to be met with comparatively little resistance from the public.

What’s at risk here is the very breeding ground for Australia’s future wealth creation.

Follow @HL_Francis on Twitter.