The uneven global recovery has central bankers stumped

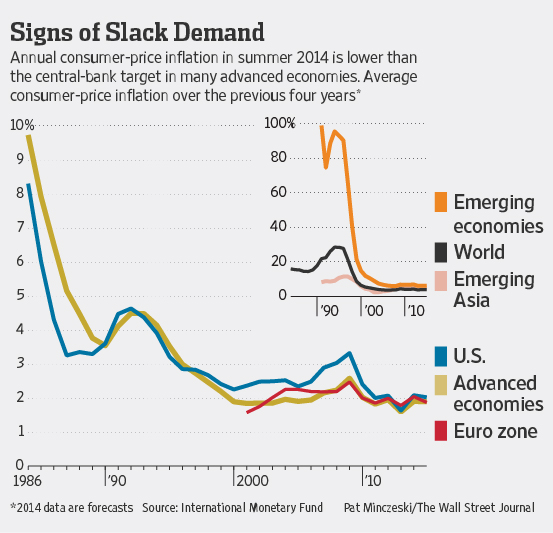

Central bankers gathering in Jackson Hole this week confront a global economy that has once again disappointed, leaving them reluctant in some places and unable in others to turn off spigots of easy money employed since 2008 to boost growth.

Federal Reserve officials -- puzzled by the combination of erratic US economic growth and robust hiring -- are waiting for more evidence that strong job gains can continue before they start raising short-term interest rates.

Elsewhere, officials are debating whether to do more, not less. China -- the world's second-largest economy, after the US -- is struggling to meet the government's growth target, and some market analysts expect interest-rate cuts. Japan, the world's third-largest, stumbled after the government raised consumption taxes and the Bank of Japan is pressing forward with securities-purchase programs aimed at boosting growth. Germany, the fourth-largest, contracted in the second quarter and the European Central Bank is experimenting with negative interest rates. The UK economy is perhaps the best-performing in the developed world, but its central-bank leader is reluctant to respond by raising short-term interest rates.

"The global recovery has been disappointing," Fed Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer said in a speech in Stockholm earlier this month. "With few exceptions, growth in the advanced economies has underperformed expectations of growth as economies exited from recession. Year after year we have had to explain from mid-year on why the global growth rate has been lower than predicted as little as two quarters back."

This leaves central bankers in an awkward position. Many worry the low interest rates they're employing to encourage borrowing and spur growth could spark a new financial bubble. In places such as London and Vancouver, real-estate prices have soared, and Fed officials are uncomfortably watching a boom in US leveraged-loan issuance and junk bonds. For now, they are depending on unproven regulatory policies to prevent another crisis and leaving low interest-rate policies in place.

Central Bank Watch

Here is how the central banks in four major advanced economies have moved two key levers of monetary policy in recent years, and how two important economic indicators have responded.

The Fed is on track to end a bond-purchase stimulus program in October. Officials have for months had their eyes on mid-2015 -- and possibly later -- as the time to start raising short-term US interest rates from near zero. The fast decline in the US jobless rate to 6.2 per cent in July from more than 7 per cent a year ago, coupled with improvement in other labor-market measures and modest increases in inflation, has sparked an intensifying debate inside the Fed about whether rate increases might need to come sooner, possibly as early as March next year.

For now, however, Fed officials want more proof that labor-market gains can be sustained.

John Williams, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, said in an interview with The Wall Street Journal he expects the Fed to hold off on rate increases until next summer. He might move that date up if the jobless rate keeps falling at a fast rate of a percentage point a year, but he said doesn't expect it and noted it hadn't moved much in the past four months.

Among his concerns is the uneven pace of global growth. "The cross currents are really strong," he said. "Typically countries are moving together."

Fed chair Janet Yellen will set the tone for this week's Jackson Hole meetings with remarks Friday on labor-market developments. For much of this year, she has pointed to slack in US labor markets -- such as an abundance of part-time workers who want full-time work -- that is keeping inflation and wage growth slow. Still, most Fed officials have been surprised by how fast the US labor market has improved this year even though the economy contracted in the first quarter.

In the UK, Bank of England officials also are treading carefully. The UK is forecast by the International Monetary Fund to be the fastest-growing advanced economy in 2014 after several years of near-stagnation. The BoE expects British economic output to expand 3.5 per cent this year, according to its latest forecasts. Rapid growth has sent unemployment tumbling.

Two of the nine central-bank officials -- Martin Weale and Ian McCafferty -- this month called for a quarter of a percentage point rise in the BOE's benchmark interest rate to keep inflation in check, according to a record of the discussions. But Bank of England governor Mark Carney subscribes to the view that a rate rise now would be premature, and most of his colleagues agree.

They believe that weak wage growth reflects economic slack that will keep price pressures at bay. They also fret that Britons would struggle to cope with higher borrowing costs, potentially putting the brakes on growth. And officials are wary of threats to the economy from overseas, including a stalled recovery in the neighboring euro zone and unrest in Ukraine and the Middle East.

"Sustained economic momentum is looking more assured," Mr. Carney said on August 13, but he added Britain's expansion "faces some challenges" and policy makers won't rush to raise rates as long as inflationary pressures are muted.

The BoE in June took steps to curb risky mortgage lending in an effort to prevent another destabilizing housing boom. But its efforts have focused on making sure Britain's banks are strong enough to withstand unexpected losses. Officials acknowledge there is little monetary policy can do to curb global risk taking that is fueled, in large part, by the Fed's easy-money policies.

China's growing challenge was highlighted by weaker-than-expected manufacturing data Thursday by HSBC. "Economic recovery is continuing, but its momentum has slowed again," HSBC economist Qu Hongbin said about the bank's China Manufacturing Purchasing Managers Index, which fell in August to a three-month low.

That tepid factory data came a week after the People's Bank of China set off alarm bells by reporting that its broadest measure of new lending had plunged by two-thirds in July from the previous month. That suggested that several months of what's called in China "mini-stimulus" spending on infrastructure, transportation and information technology and eased liquidity by the central bank hadn't yet done much to lift the economy.

"We maintain our forecast of two interest rates cuts" in the second half "to help ease debt burdens, support demand, and mitigate financial risks," Barclays said in a report following the data. "We continue to believe the government faces a trade-off between 'tolerating lower growth' and 'rolling out more stimulus' amid a property market correction and uncertain external demand," the firm's economists wrote.

The Bank of Japan only belatedly joined the global central-banking stimulus binge after the 2008 financial crisis. In contrast to the Fed, it is still in the early stages of a program of asset purchases, known to some as quantitative easing, or QE, aimed at boosting growth. The BoJ has an open-ended commitment to keep buying assets at an annual pace of ¥60 trillion to ¥70 trillion (about $US580 billion to $US670 billion).

The big debate now in Japan isn't about when the central bank will cut back, but rather about whether it should expand that program. A spate of weak summer data following an April sales tax hike has been "bolstering the case for policy makers to do more," research firm Capital Economics said in a report Monday.

And for all the BoJ's optimism about the resilience of domestic demand in Japan, policymakers regularly cite uncertainty about the durability of the global recovery as the biggest risk to Japan's rebound.

"I am paying utmost attention to the risk of weaker-than-expected growth for the Chinese economy," policy board member Takahide Kiuchi told regional business leaders in a July 31 speech.

-- Jason Douglas and Jacob M. Schlesinger contributed to this article. Originally published in The Wall Street Journal. Republished with permission.