The RBA steps towards a housing policy highwire

Recent comments by the Reserve Bank of Australia indicate that an intervention in the housing market may be getting closer, though by no means is it over the line. Macroprudential policies would allow the RBA to avoid raising rates simply to mitigate an overheated housing market -- and that is the type of policy flexibility that the RBA would welcome right now.

The RBA minutes, released yesterday, suggest that macroprudential policies are gaining traction among senior officials and members of the board. At its March meeting, members discussed the experience of other countries that have utilised macroprudential policies and their possible application for Australia (A rates bet as safe as houses, March 18).

The members concluded that present conditions in the household sector “did not pose a near-term risk to the financial system”. But we cannot discount the possibility. While speaking before the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics, RBA Governor Glenn Stevens said that it would not be desirable for household debt to rise much higher.

The RBA may not currently believe that the housing sector poses a systemic risk, but the potential certainly exists. Housing accounts for over 60 per cent of household wealth and is valued at over $5 trillion -- more than three times nominal GDP. Our major banks have massive exposure to housing and state governments are overly reliant on stamp duty to balance their books.

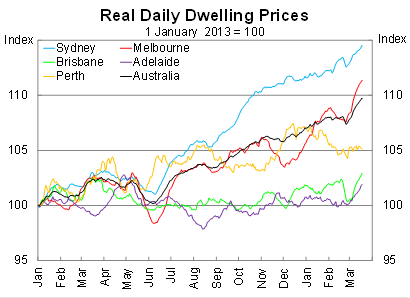

Since the meeting took place, house prices have surged further with real prices up 1.8 per cent over the March to date. Though I’m not a huge fan of daily data -- too much noise compared with signal for my liking -- the data likely provides a solid indication of what to expect from the March quarter. The argument for RBA intervention is only rising with each passing month.

A recent Freedom of Information request provided some insight into the RBA’s recent thinking. Among the macroprudential policy tools examined, including New Zealand-style caps on high loan-to-valuation ratios, the RBA head of financial stability Luci Ellis believes that “the most promising policy response seems to be to introduce a regulatory regime that automatically requires larger interest buffers in loan affordability calculations when interest rates are low” (The RBA’s radical remedy for souring house prices, March 11).

So, for example, banks would be forced to consider whether a loan applicant could service the loan if lending rates rose by 4 percentage points as opposed to current lower buffers. The advantage of this method over caps on high LVR lending is that it doesn’t exclude lenders who can service high LVRs from the market. On the downside though, it doesn’t protect high LVR borrowers from suffering negative equity during a housing downturn.

It should be made clear that macroprudential policies are not designed to fix housing affordability, merely to limit the systemic risk arising from an asset class that is arguably too big to fail. It is no silver bullet and we need widespread tax and land supply reform to improve housing affordability in the long-term.

Initially macroprudential policies may, in fact, harm affordability given they are likely to disproportionately affect younger borrowers. But these are also the borrowers most in need of protection in case a downturn occurs.

Perhaps most importantly, the use of macroprudential policies would provide the RBA with a great deal of policy flexibility. The RBA certainly will not want the housing sector to take their interest rate regime hostage; they don’t want to raise rates simply to mitigate an overheated housing sector.

Macroprudential policies could create the best of both worlds for the RBA. They can slow the housing sector but also maintain support for other sectors of the economy that are still in a bit of a rut. Interest rates, on their own, are likely to be too blunt an instrument to balance the needs of the housing market and the broader economy.