The RBA could consider an unconventional future

Summary: Australia may be just one financial shock away from deploying unconventional monetary policy. |

Key take out: With limited conventional monetary policy firepower remaining, the RBA might have to consider quantitative easing, 'helicopter money', and similar measures. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Economics. |

Central banks have a well-deserved reputation for being dour and uninteresting. Their monthly and quarterly reports are often an exercise in tedium and a cure for insomnia, and their direct communication with the public is often viewed as cryptic – full of fascinating insights only if you are willing and able to read between the lines. Most people aren't.

Yet there is nothing boring about the methods that central bankers have utilised to boost economic activity and financial markets in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. From quantitative easing and negative interest rates to forward guidance and helicopter money, the world of central banking is flush with innovative ideas on how best to fix the problem of excess savings and inadequate global demand.

Until recently this wasn't a conversation to be found in Australia. We managed to avoid the worst of the global financial crisis due to a strong fiscal response from the Kevin Rudd government and Chinese stimulus that boosted demand and the prices of Australian commodities.

While the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of England cut interest rates to zero per cent – or close enough – the Reserve Bank of Australia made do with a cash rate of three per cent (then a record low). As the Federal Reserve pursued quantitative easing, the purchase of government and corporate bonds along with asset-backed and mortgage-backed securities, the RBA deemed conditions strong enough to start raising interest rates in October 2009.

The past four years, though, haven't necessarily been kind to the Australian economy or the Reserve Bank. Commodity prices and our terms of trade took a tumble and dragged down domestic income growth. We have had an ‘income recession' for the best part of three years, which has seen the nation take a pay cut as mining profits plummeted. Wage growth and then inflation soon followed.

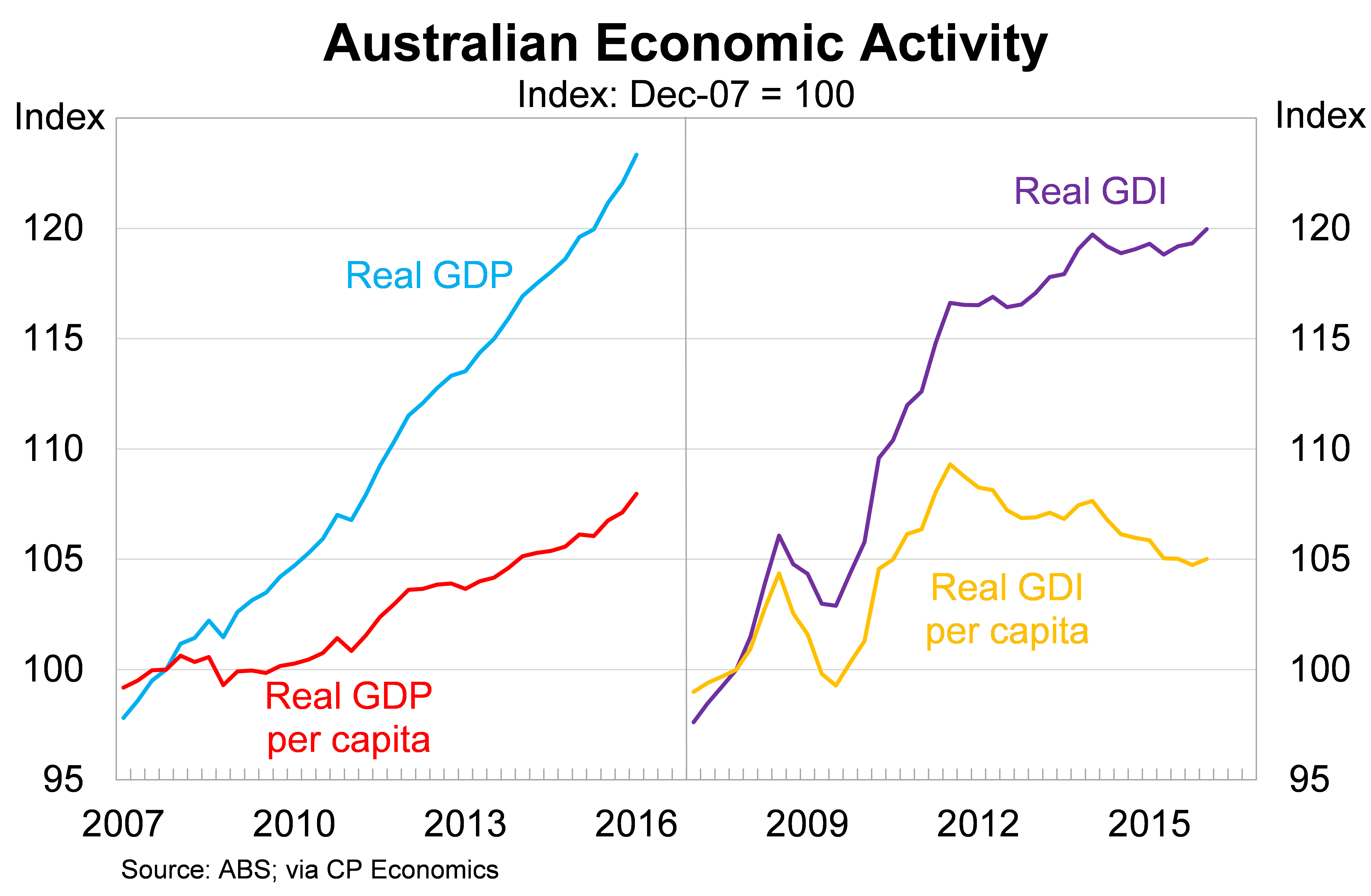

This income recession is detailed in the graph below, in both aggregate and per capita terms, including a comparison with real GDP. According to real gross domestic income, which adjusts real GDP for changes in our terms of trade, Australian living standards have declined for the past 4½ years.

Today the cash rate sits at 1.75 per cent – well below its trough during the GFC – and is expected to be cut by a further 25 basis points when the RBA meets on August 2. Our economy might still be stronger than our peers but we are now not so far removed from other advanced economies such as the United States, England and the eurozone.

The RBA is running out of ammunition

We also face a bit of a problem: we are rapidly running out of monetary policy ammunition. In other words, the RBA may soon be forced to embrace unconventional monetary policy in line with policies utilised by other central banks globally.

According to RBA deputy governor Philip Lowe, who becomes governor in September, cutting the cash rate loses some of its effectiveness as it approaches one per cent.

“Once you get below some certain level of very low interest rates … [the] incremental benefit from lowering them further is quite small,” Lowe said during a December 2012 event. “Somewhere around one per cent plus or minus a bit – I think once you get there, other options of unconventional monetary policy may become more viable.”

There are a range of reasons why this may be the case. Cutting interest rates to a level that many associate with a crisis could, for example, dampen confidence. It is also true that businesses often fail to factor lower interest rates into their investment decisions. Meanwhile, the search for yield may result in investors taking on greater risk than they would during more normal times. Offsetting this, an interest rate cut – even at low levels – does free up household and business balance sheets, supports asset prices and reduces the value of the Australian dollar.

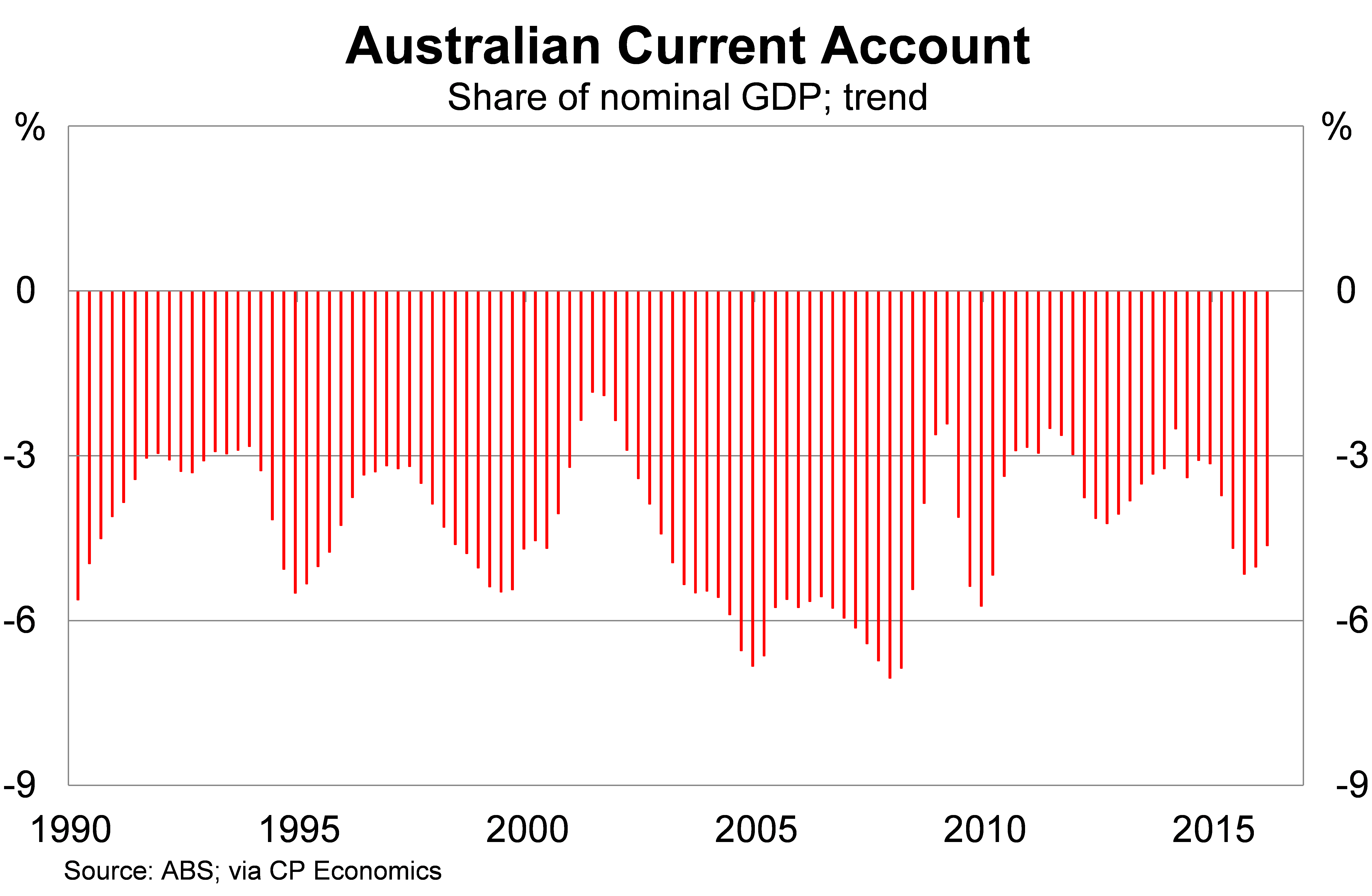

One important consideration is that lower interest rates put pressure on Australia's current account deficit. Australia relies on foreign capital to support the living standards that we have grown accustomed to. As a result, we must maintain an interest rate that makes Australia an attractive destination for foreign capital.

That hasn't been a problem over the past eight years, with Australian assets offering exceptional yields compared with overseas equivalents. But as our cash rate heads towards zero Australia becomes a less attractive destination. Cut rates too far and the Reserve Bank risks encouraging capital flight. In that situation lower rates could actively harm economic activity.

Given the delicate nature of the situation, both with regards to existing monetary policy and the economic outlook, it is perhaps no surprise that the Reserve Bank has given serious consideration to what they will do once conventional monetary policy is exhausted.

“As you would expect, we have considered what lessons can be drawn for Australia by looking at the experience of other central banks that have adopted various unconventional measures,” RBA assistant governor Christopher Kent said in an interview last week.

The experience of the Federal Reserve and other high-profile central banks, including the Bank of Japan, provides important insight for our Reserve Bank. These banks provide some guidance on which policies are likely to work and which can best be avoided.

Will Australia ever need unconventional monetary policy?

Kent doesn't think so, saying that the likelihood of their usage is “very remote”, and yet if Lowe is correct that standard monetary policy is effectively exhausted at a cash rate of around one per cent then we are just one small financial or economic shock away from the RBA dipping into their bag of tricks. There is no shortage of potential triggers with the ‘Brexit', Deutsche Bank, the Italian banking system and China to name just a few.

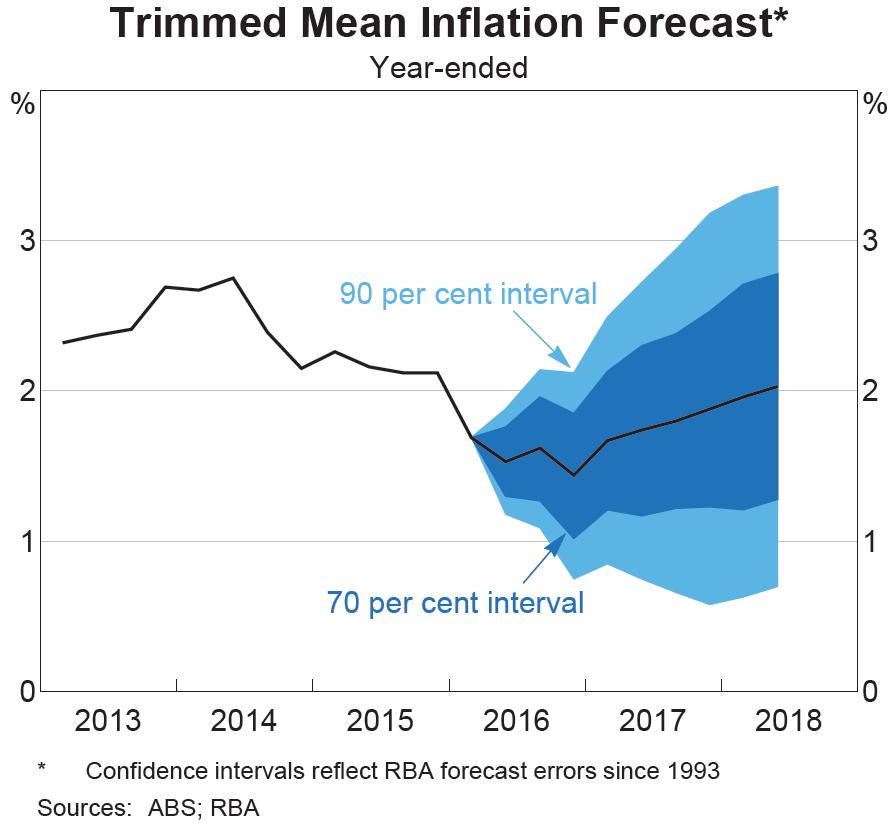

Furthermore, core measures of inflation currently sit at their lowest level in 30 years and the RBA expects inflation to remain below the lower end of its 2-3 per cent annual inflation target through to mid-2018. The RBA's inflation forecast, included in the graph, warrants a cash rate of below 1.5 per cent.

According to Kent, “policies should be tailored to individual country circumstances” rather than a one-size-fits-all approach. Kent acknowledges that “different unconventional policies could be used at the same time, and such a combination may be more effective than any one type of policy in isolation.” Finally, Kent noted that “there is evidence that unconventional policies have provided a measure of stimulus, although it appears that there are diminishing returns.”

If I was to be critical of the unconventional measures utilised by most central banks it is that they don't offer a lot of bang for their buck. Central banks have spent trillions trying to stimulate economic activity and not a lot of progress has been made.

What tools does the RBA have to work with?

Traditional quantitative easing, including the purchase of assets such as government and corporate bonds as well as mortgage-backed securities, is one tool that may be considered. These policies are designed to drive down bond yields, and therefore long-term borrowing rates, as well as providing liquidity to banks and other financial institutions. This is consistent with the quantitative easing programs utilised by the likes of the Federal Reserve and ECB.

The main problem with this from an Australian perspective is that we don't have a great deal of state or federal government debt, which means that there are not a lot of government bonds to buy. Furthermore, we have a fairly shallow corporate bond market since most Australian businesses are generally considered too small to tap these markets.

A traditional quantitative easing program might best be used to provide liquidity to the financial system during times of stress. The RBA could buy bad assets, since they are better placed to manage the risk, and free up bank balance sheets.

Negative interest rates aren't an attractive option according to the Reserve Bank. So don't expect them to follow in the footsteps of the ECB or Bank of Japan. As I said earlier, we'd likely face a current account crisis in the event that we went down this path so it's a good thing it's not under serious consideration.

Purchasing foreign assets is a third option though it may raise the ire of foreign central banks since it would be viewed as exchange-rate manipulation. Be that as it may, directly weakening the dollar may have appeal given its importance to our economic transition. The main issue is that almost every central bank wants a lower currency and the major foreign central banks tend to enjoy a greater influence on foreign exchange markets.

A final option is one that, until recently, was considered unthinkable, but is slowly becoming accepted globally. I am talking of ‘helicopter money', which basically refers to a central bank directly financing government spending via the printing of more currency.

The evidence on ‘helicopter money' suggests that it offers a much higher return than quantitative easing. But it is controversial since in the past it has been associated with hyper-inflation or extremely fast growth in prices. That isn't really a risk though in a world characterised by low inflation and inadequate demand.

A bigger concern though might be that governments will become addicted to the money they receive from central banks. It may become difficult to wean governments off monetary support and it could prove problematic for fiscal planning if a central bank pulls money from the budget as conditions improve.

Investors have come to love quantitative easing and they'd be forgiven for embracing the Australian equivalent. Quantitative easing funnels money into financial markets and overwhelming those funds have been used to increase asset prices.

The influence is so great that markets have begun to react positively to bad news – any news that increases the likelihood of looser monetary policy is considered welcome. The most recent example is that of the ‘Brexit', which traditionally would be viewed as a negative for both the economy and financial markets. It is still a negative for the economy but financial markets are licking their lips at the prospect of another round of quantitative easing.

The path that will have the greatest positive impact on the economy and therefore the underlying fundamentals is ‘helicopter money' since that policy puts money directly into the hands of households and businesses and directly boosts demand. Despite being a positive for the business sector it is unlikely to have the same impact on asset prices.

As it stands this is not an immediate issue for the Reserve Bank as they still have some ammunition left. But it is an issue that is likely to dominate economic and financial debate over the next few years. Japan is reportedly on the verge of trialling ‘helicopter money' and if it works there will be no shortage of central banks looking to follow suit. Luckily for Australia our economy is travelling just well enough that we get to wait and see whether it works before we need to try it ourselves.