The 'new normal' has neutralised the RBA

The zero lower bound could become the ‘new normal’ for monetary policy but even if it doesn’t our cash rate is set to be consistently lower than we have become accustomed to during the Reserve Bank of Australia’s inflation-targeting period. But if the RBA has less room to move, the onus will fall on our state and federal governments to ensure that Australia doesn’t suffer a decade of disappointment.

Prior to the global financial crisis, conventional economic wisdom suggested that a nominal cash rate of zero per cent was a phenomenon reserved for Japan or countries suffering a severe recession. For countries in the latter camp, it was simply a temporary stop on the path to greater economic times.

But such thinking is no longer appropriate. Most of the developed world has now had seven years to get used to the zero lower bound on interest rates. Not to mention the increasingly conventional quantitative easing.

The Federal Reserve lowered rates to zero per cent -- or near enough -- in late 2008; the Bank of England in early 2009; while the inflation hawks at the European Central Bank paid a heavy price for taking too long to join their central bank peers.

But the leader of the pack is clearly the Bank of Japan, which has been living with a zero per cent nominal cash rate for the best part of 20 years.

In that regard, the Japanese economy remains as important as it ever was. Not due to trade or technology -- areas where Japan once dominated -- but because it provides a roadmap for other countries to follow and the pitfalls and mistakes to avoid.

The nasty reality is that a zero per cent nominal cash rate -- or thereabouts -- may soon be the ‘new normal’ for countries such as the United States, Britain and much of the eurozone. This was the idea laid out by American economist Lawrence Summers last year.

Summers has suggested that the slow recovery from the GFC might reflect broader structural factors that have been weighing on the US economy for years. He notes that credit bubbles and loose monetary policy were only sufficient to generate moderate economic growth throughout the 2000s.

He has also argued that the zero lower bound constrains nominal interest rates to the extent that real interest rates (nominal rates less inflation) may not be able to fall low enough to boost investment and push the economy towards full employment.

The neutral cash rate -- the rate consistent with full employment -- is declining throughout the developed world. BoE governor Mark Carney recently suggested that the neutral rate in England was around 2.5 per cent; while the outlook for the Fed suggested a neutral rate of close to 4 per cent.

Both are well down on estimates of the neutral rate prior to the GFC, but they remain estimates, and as the recovery continues to muddle along it is likely that these estimates -- particularly for the Fed -- could decline further.

So is this relevant to Australian households, businesses and our local, state and federal governments? The unfortunate answer is yes -- and there is growing evidence that the neutral rate has declined in Australia. Low rates are here to stay.

First, trend growth is showing signs of moderation. The mining boom resulted in a period of unprecedented prosperity but with our terms of trade set to decline and an ageing population, the next decade will be a far greater challenge.

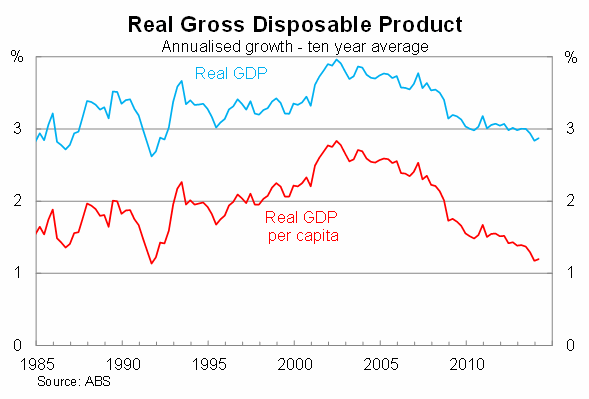

The graph below, which shows annualised growth averaged over a 10-year period, highlights this recent moderation. It is particularly noticeable that trend growth has slowed to its lowest level since our last recession.

Over the next decade Australia’s business cycle will inevitably fluctuate around a lower mean level. This is notable since the lower the level of trend growth, the more likely it is that an economy will dip into a recession during a downturn.

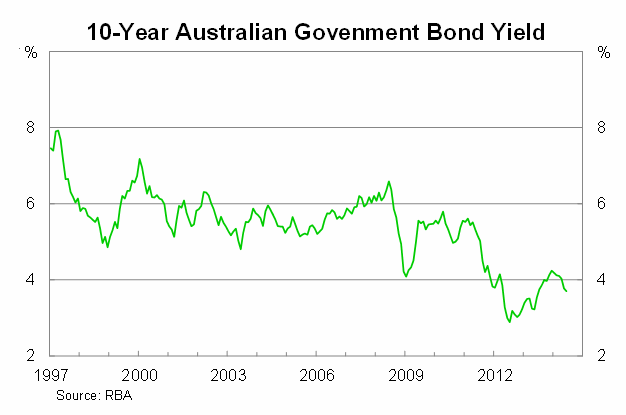

In addition to our softer growth outlook, government bond yields have trended downwards since the beginning of the GFC, reflecting the weaker outlook for the Australian economy. Ten-year government bond yields are around 170 basis points below their inflation-targeting average. The market is effectively assuming that over the next decade the cash rate will average around 3.5 per cent.

Our cash rate currently stands at 2.5 per cent, and is negative in real terms, but I have argued recently that we may need to lower it further to foster sustained growth in household spending and business investment.

The response to looser monetary policy has been relatively mild thus far and mostly felt through residential investment. Non-mining investment has been particularly ordinary, indicating that the return on capital has declined considerably throughout the sector. In previous cycles, a 2.5 per cent cash rate would have ushered in a boom for non-mining investment.

The Australian economy faces a range of challenges over the next couple of decades but they are challenges that will be shared by other developed countries, such as the United States and Britain. The one challenge unique to Australia is the decline in our terms of trade, which may see our economy underperform compared with other developed countries over the next decade.

Australia will need forward-looking policymakers to navigate these challenges. If the neutral rate is declining then the RBA will have less ammunition to support the economy than it did during the GFC. A greater burden will fall on the shoulders of our state and federal governments, who must work to usher through reform to boost labour and multi-factor productivity growth.

A failure to do so, or the belief that the RBA will do the heavy lifting, will set Australia up for a decade of disappointment.