The missing piece of the audit puzzle

The most glaring problem with the Commission of Audit is what they didn’t cover: revenue. A strong assumption for tax receipts suggests that even with the range of reforms suggested by the commission, the federal government will fail to reach its goal of a surplus of 1 per cent of nominal GDP by 2023/24.

Consistent with its terms of reference, the Commission of Audit provides an ambitious program for reform on the expenditure side, with estimated savings of between $60 and $70 billion per year by 2023/24. In addition, they recommend the most extensive reform of federalism since the federation began in 1901.

The Commission to its credit has not ignored the big issues. They recommend extensive reform of the aged pension and health care – the two biggest long-term challenges for the budget. Welfare reform, where recommended, has wisely been centred on directing funds towards those most in need rather than on the middle and upper-class.

It is estimated that the age pension will rise to $72 billion by 2023/24 (up from $40 billion at present). Aged care spending is set to double over the next decade.

Medicare is expected to rise by 7.1 per cent per year until 2023/24 and continue expanding rapidly from there. Hospital spending is anticipated to rise to $38 billion from $14 billion over the decade.

Though the review and political debate has been centred on the immediate budget crisis -- which many economists consider a figment of the Coalition’s imagination -- the reality is that we do have a genuine long-term crisis.

We are on an unsustainable path that doesn’t cause problems now or a decade from now but has significant long-term implications. Without reform -- of the tax, health and aged variety -- the budget will inevitably deteriorate to the extent that short-term solutions and most other reforms would be ineffective.

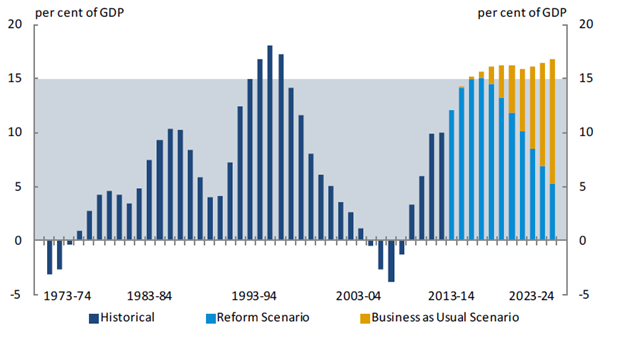

The commission created two scenarios for their analysis; the first a ‘business as usual’ fiscal scenario is based on current assumptions included in the budget and includes no reforms. The ‘reform’ scenario is just that, a scenario where extensive reform is undertaken across a range of programs and government departments.

In the ‘business as usual’ scenario, net debt rises to around 17 per cent of GDP. By comparison, in the ‘reform’ scenario, the budget returns to surplus in 2019/20 and the surplus rises to 1 per cent of GDP by 2023/24; net debt falls to around 5 per cent. Neither scenario should put at risk our AAA rating.

Commonwealth Government Net Debt

In both scenarios the commission has used the same profile for government receipts, with tax receipts assumed to return to 24 per cent of GDP (its average between 2000 and 2007) and total receipts (including dividends and other income) returning to 25 per cent of GDP.

The commission’s focus has largely mirrored the public’s view that recent government deficits have reflected out of control spending by the Rudd / Gillard governments. Though spending increased – in part reflecting stimulus measures during the global financial crisis but also new programs – the biggest cause of rising debt was actually the sharp decline in tax receipts.

It’s commonly overlooked but a deficit is the residual of government spending and receipts. Though it is hardly the commission’s fault, focusing merely on spending ignores half the issue. In this case ignoring half the issue creates a significant problem.

How plausible is the Commission’s assumption that tax receipts will return to its 2000 to 2007 average?

There are very real reasons why our tax base narrowed since the global financial crisis began and without tax reform it is not clear why revenue will head back towards its long-run average.

Two factors are likely to weigh on revenue over the next decade and make the budget assumption implausible.

First, the aging population will continue to hollow out the tax base, forcing the economy to rely on an increasingly smaller share of the population to support government spending. Second, the terms-of-trade will fall over the forecast horizon as mining investment reaches the production stage and the global supply of key commodities such as iron ore rise significantly.

Without significant tax reform, receipts are unlikely to meet the commission’s assumption. That level of revenue was the norm during the glory days when the terms-of-trade was high and demographics were favourable -- they will not be replicated going the other way. Nor should we pretend that they will.

The Commission of Audit provides a comprehensive review of government spending and proposes a range of useful reforms that could prove beneficial to the Australian economy and a range of reforms that the Coalition may find too radical for consideration.

But their outlook appears too optimistic since it is based on a revenue assumption that is unlikely to materialise. A more conservative approach, incorporating the impact of an ageing population and terms-of-trade deterioration, would likely result in continued deficits even in the commission’s ‘reform’ scenario.

It is time we stopped pretending that tax revenue will simply sort itself out. At the very least, we shouldn’t consider a period of unprecedented prosperity to be the ‘norm’. Tax revenues will not return to their previous highs without extensive tax reform, and pretending otherwise understates the significant long-term challenges facing our budget.