The Fed's rates rush defies logic

Summary: There is no urgent need for the Fed to tighten monetary policy but it appears likely the central bank will do so anyway. |

Key take-out: The Australian market may be hit more heavily than most from US monetary tightening, since a stronger greenback tends to weaken commodity markets. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Shares, forex, commodities. |

Are global investors ready for the US Federal Reserve to raise interest rates? Recent comments by Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen and her deputy Stanley Fischer have set the scene for a rate hike before the end of the year.

“In light of the continued solid performance of the labour market and our outlook for economic activity and inflation, I believe the case for an increase in the federal funds rate has strengthened in recent months,” Yellen said during a speech last Friday.

Fed vice-chair Fischer noted the possibility that there could be more than one rate hike by the end of the year.

Despite these bullish statements from the Fed and its two most important officials, I'm not convinced that a rate hike is in the best interests of the US economy. Nor am I convinced that "the case for an increase in the federal funds rate has strengthened in recent months".

To explain the current situation we need to focus on three economic indicators. The first is inflation, which remains below the Fed's annual target of 2 per cent. The second is non-farm payrolls, which are released on Friday night. The third is economic growth, which was released last Friday and has disappointed the market for the past six months.

As we step through these economic drivers it will become evident that there is no urgent need for the Fed to tighten monetary policy. The data itself is quite mixed, with some indicators actually becoming weaker throughout 2016.

Nevertheless, the Fed appears determined to continue on the path towards rate normalisation and investors should be prepared for greater market volatility over the remainder of the year.

Inflation

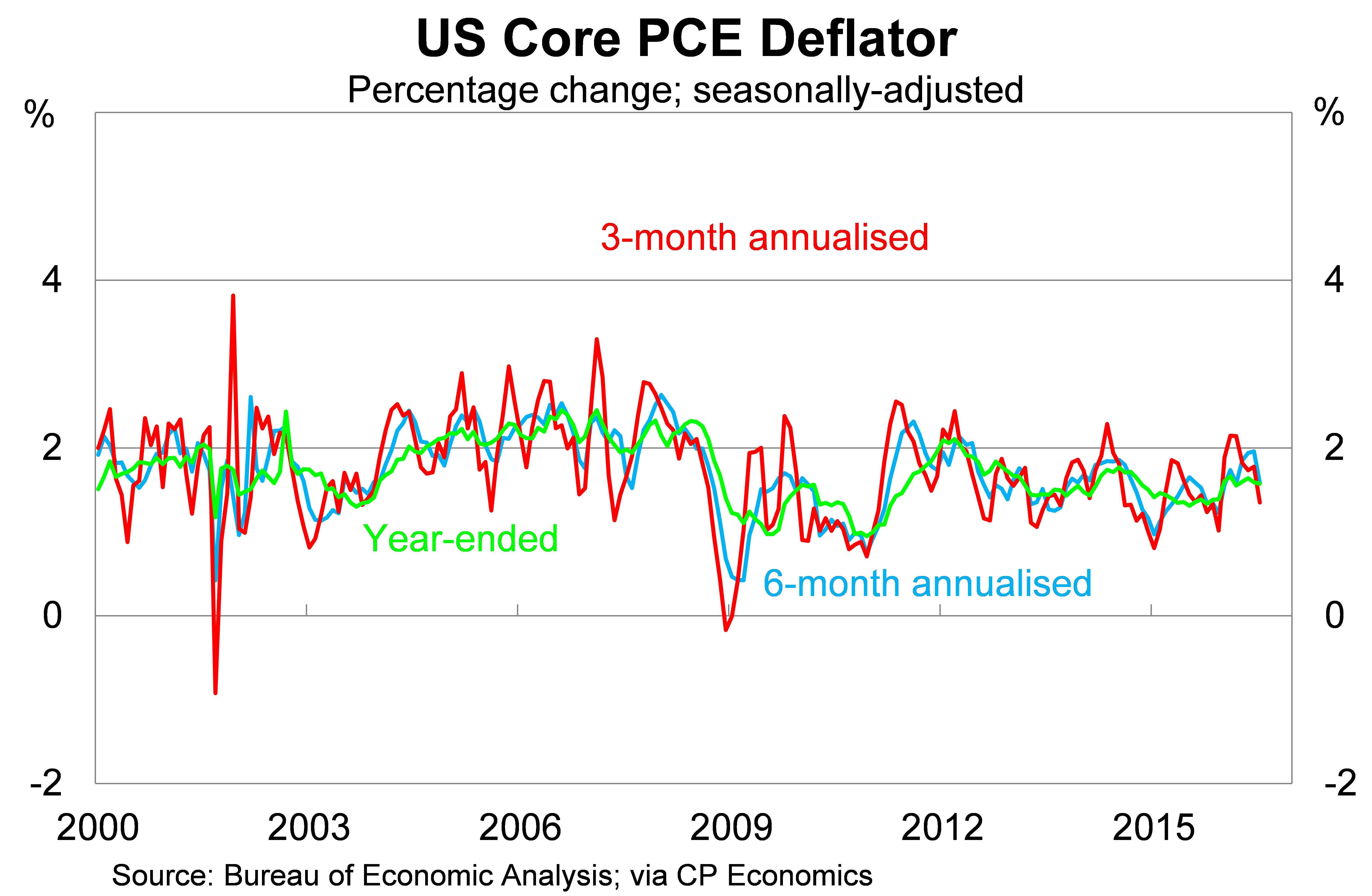

The US has a range of inflation measures – several more than Australia does – but the one the Fed places the greatest reliance on is the personal consumption expenditure (PCE) deflator. More specifically, it focuses on the core PCE deflator, which strips out the effects of volatile items such as food and energy.

New data for this measure was released earlier this week. According to the Bureau of Economic Activity, the headline PCE deflator has increased by 0.8 per cent over the past year. However, this measure has been pushed lower temporarily by lower oil and energy prices.

The core PCE deflator has increased by 1.6 per cent over the past year and remains well below the Fed's annual target of 2 per cent.

The graph below tries to identify whether inflationary pressures have built up over the past three or six months. If anything, it appears as though inflationary pressures have eased somewhat recently with both three-month and six-month annualised growth coming off their recent peaks. Overall, the inflationary environment remains quite benign.

The inflation figures, by themselves, do not warrant a rate cut. The core PCE deflator has hit the 2 per cent annual target in just five of the past 94 months. To justify tighter monetary policy the Fed needs the support of another data source, which brings us to employment.

Employment

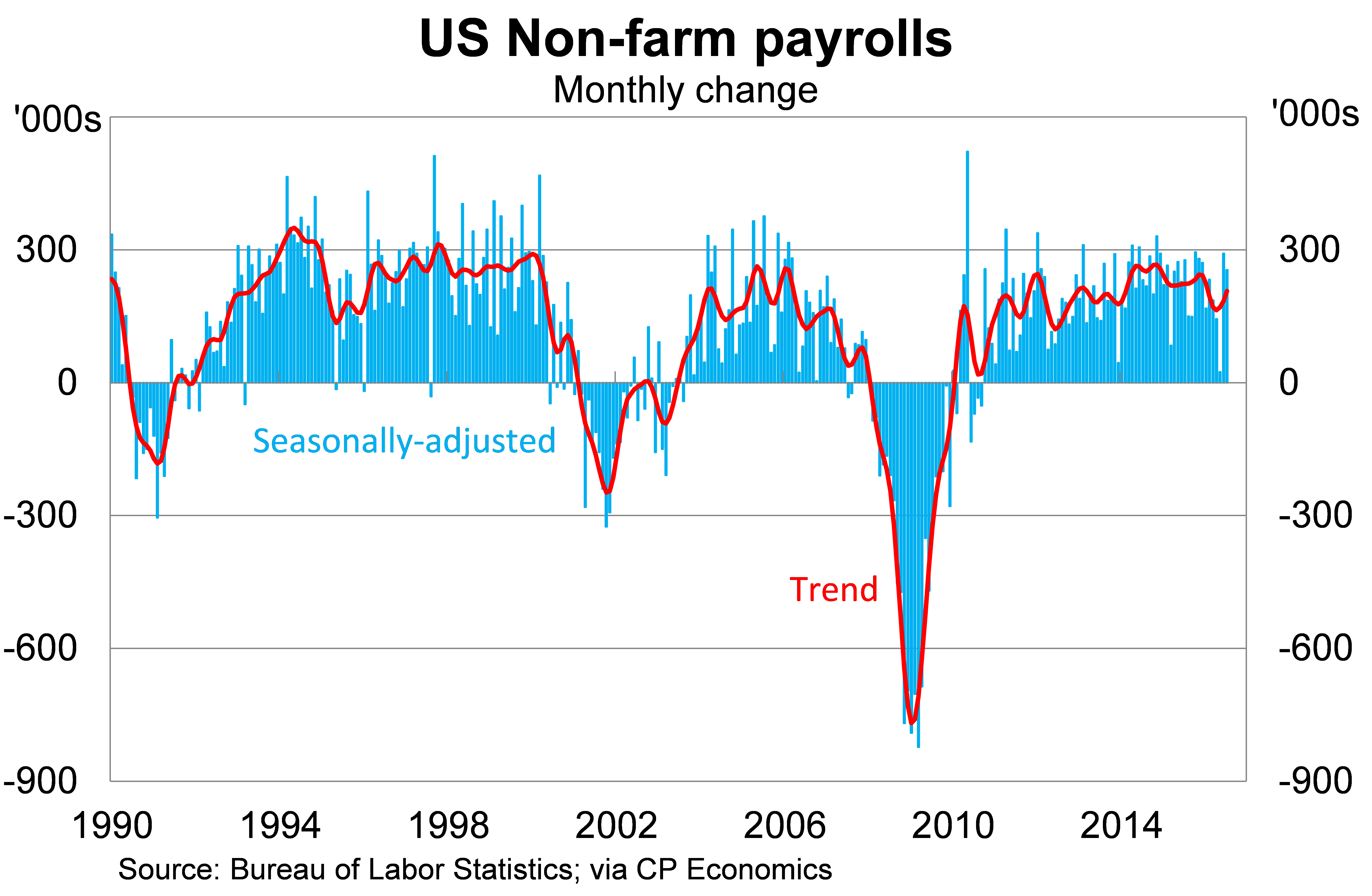

The Fed focuses on a range of labour market indicators to support its assessment of inflation and economic growth. The unemployment rate and employment growth (known in the US as non-farm payrolls) are the two most important labour market indicators. The Fed watches closely to see how developments across the labour market feed into wage growth and inflation.

The US labour market went through a bit of a rough patch but seems to have come through the episode stronger than ever. Non-farm payrolls is expanding at a rate of 207,000 people a month on a trend basis. This is a little weaker than last year, but not materially so.

The US unemployment rate currently sits at 4.9 per cent and has hovered at around that level throughout 2016. Participation in the labour force has increased modestly, which means that spare capacity across the US labour market continues to diminish.

The labour force figures presents a more compelling case for a rate hike. When Yellen says that “the case for an increase in the federal funds rate has strengthened”, she is largely focused on these labour market figures.

Perhaps most heartening for the Fed is that wage growth has started to pick up. Nominal wages have increased by 2.8 per cent over the past 12 months, which is the strongest rate of growth since June 2009.

So far that hasn't translated into higher inflation but the optimists at the Fed would argue that it is only a matter of time before stronger wage growth is passed on to households via higher prices.

One set of data should give the Fed cause for concern. We now turn our attention to economic growth.

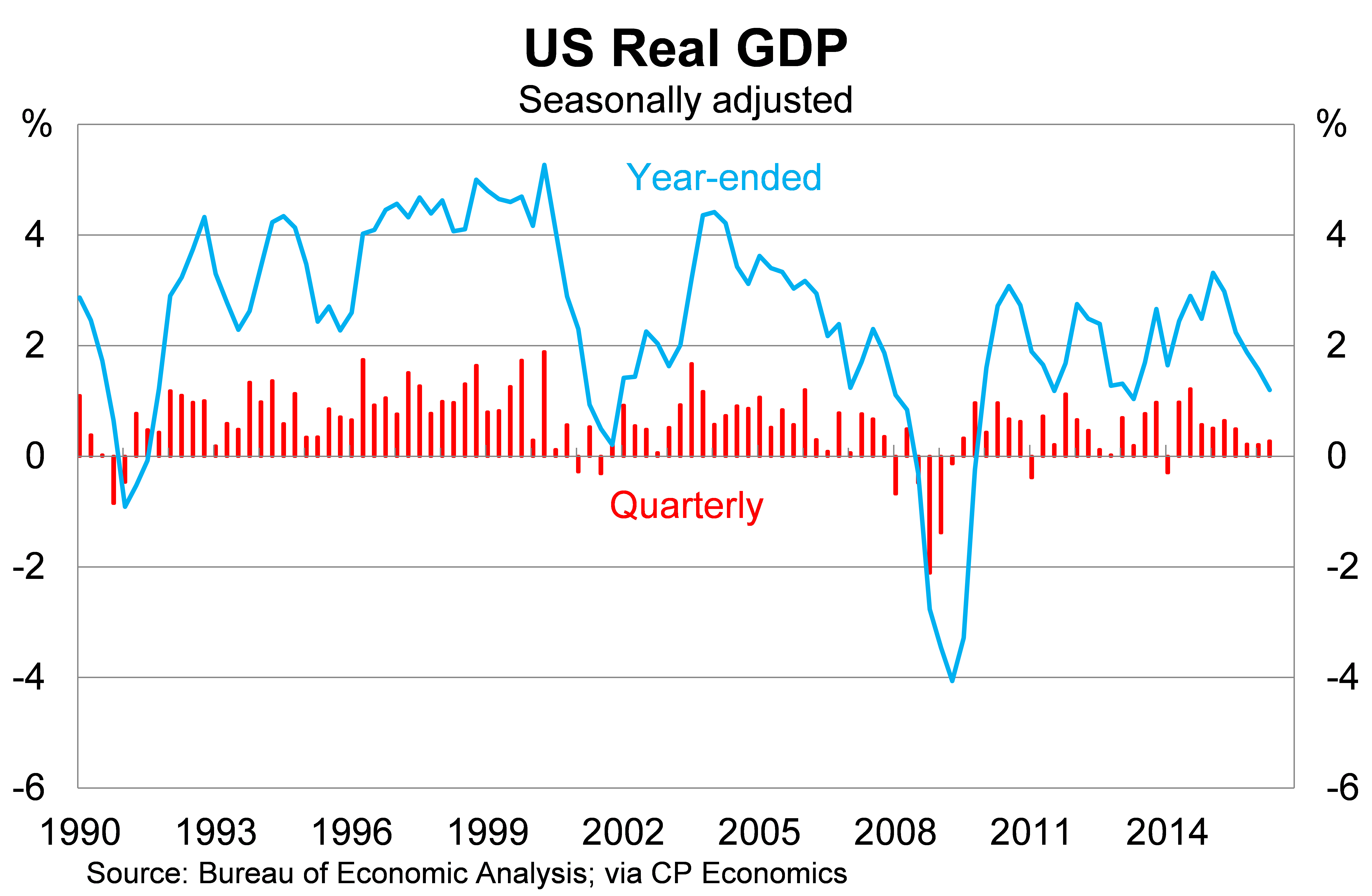

Economic growth

Real GDP across the US has increased by 1.2 per cent over the past 12 months. Annual growth has more than halved over the past year and currently sits at its lowest level in three years.

Employment growth has traditionally lagged economic activity; that weakness across the broader economy leads to softer labour market conditions. One risk associated with raising interest rates this year is that it exacerbates this recent trend; leading to softer growth and undermining the recent strength in employment.

Furthermore, it's exceptionally rare for a central bank to raise rates when economic growth is tracking at such a low level. So far the Fed has decided to ignore or downplay these growth figures in favour of the stronger labour market indicators.

It should be clear by now that the decision to raise the federal funds rate is far from straightforward. My personal view is that there should be no great urgency to tighten policy; inflation is well contained and is unlikely to break out given low inflation is now a global phenomenon.

Furthermore, the downside risk of tightening too early is simply too great to ignore. In the worst-case scenario, the central bank risks undermining economic growth and destabilising capital flows across the globe. The risk of tightening too slowly amounts to little more than a brief period where inflation exceeds its annual target.

Nevertheless, the Fed appears committed to tightening policy later this year. Its view could change as new data is released but for now we should take the Fed at its word. A rate hike will translate into a stronger US dollar – lowering the value of the Australian dollar – but will also shift global capital flows out of emerging markets towards safe-haven assets in the US.

This process has already begun, based on the probability of a US rate hike, but it could prove disruptive for financial markets.

The Australian market may be hit more heavily than most since a stronger US dollar tends to weaken commodity markets. For years financial markets have relied upon loose monetary policy to support asset prices; further rate hikes by the Fed represents the first real test to this new world order.