Regulators are finally bringing balance back to the housing market

Following months of speculation (and lots of speculative activity), the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority appear all but certain to introduce macroprudential policies to ease mounting pressure in Australia’s property sector. With property prices in Sydney continuing to rise at a rapid rate, it’s a move that is well overdue.

According to the RBA’s Financial Stability Review, “the Bank is discussing with APRA, and other members of the Council of Financial Regulators, additional steps that might be taken to reinforce sound lending practices, particularly for lending to investors".

That means the introduction of macroprudential policies -- measures designed to slow lending that are not associated with monetary policy -- and they are well overdue. Although it has only recently become obvious to the RBA that risks in the housing sector have become unbalanced, those risks have been in place for the best part of year.

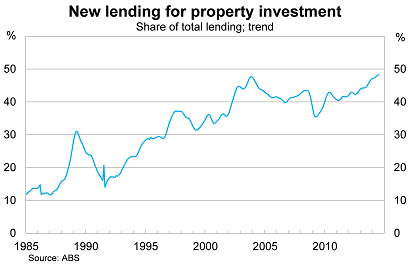

Speculation has increased sharply over the past couple of years, with investor activity accounting for a record share of total mortgage lending. According to the RBA, lending activity is “becoming unbalanced” particularly in Sydney and Melbourne.

The RBA isn’t completely convinced that this lending represents a systemic risk, noting that most of the “risks associated with the lending behaviour are likely to be macroeconomic in nature". But broader risks remain due to the simple fact that we are dealing with a $5 trillion asset class, which accounts for a majority of household wealth, and is the dominant source of bank profitability.

Australian banks are already among the most leveraged financial institutions in the world, using loose capital requirements on mortgages to boost profitability year after year. Reckless lending has only been enhanced by the government’s implicit guarantee, which all but ensures that the major banks don’t bear the full risk of their actions.

Right now they don’t appear to be holding a considerable number of bad debt,s but that would quickly change if Australia suffered a recession or a considerable income shock and rising unemployment.

The push for macroprudential intervention has gained momentum in recent weeks. It was only in August when RBA governor Glenn Stevens appeared against such measures, although more recently he has suggested that baby boomers might do well to diversify their asset holdings (Have baby boomers made a big investment mistake?, September 4).

Federal Treasurer Joe Hockey and the G20 gave the go-ahead on the weekend, giving the RBA and APRA sufficient political cover to pursue a broader set of policies. They will likely need it, given any intervention that is seen to reduce house prices or the availability of credit will not be popular even if it is in the public interest.

“Any action needs to be specific, it needs to be very targeted and it needs to have some capacity to be time-limited,” Hockey said.

If the RBA and APRA do intervene they will be following in the footsteps of the Bank of England and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, among others.

Back in June, the BoE introduced new rules under which only 15 per cent of new home loans will be allowed to have loan-to-income ratios of more than 4.5 (APRA’s inaction brings a housing crisis closer, June 30). That followed the RBNZ decision to introduce temporary restrictions on lending with high loan-to-valuation ratios.

The RBA and APRA are unlikely to pursue such measures. Instead, assuming macroprudential policies are pursued, it will likely be in the guise of an enhanced interest rate buffer during periods when interest rates are low. That seems sensible and on the brief occasions that the RBA has mentioned macroprudential policies, it seems to be the preferred form of intervention.

Much will be said about macroprudential policies -- indeed, much has already been written -- but it’s important to remember that they are primarily designed to reduce the systemic risk within the financial sector.

These are not affordability measures and to some extent may make it more difficult for first-home buyers. But do you really want younger Australians -- among the most financially vulnerable members of society -- to be buying property at sky-high prices when those prices pose a systemic risk to the entire financial system?

Fixing affordability will be a much tougher task and requires reform to both demand and supply factors. On the demand side, we need to address government policies such as negative gearing and the capital gains tax. Macroprudential policies will ease demand for bank lending but the Murray inquiry also has a role to play by encouraging greater capital requirements and requiring a payment for the government guarantee that underwrites the bank’s behaviour (Murray must address the moral hazard in housing, July 16).

On the supply side, the onus is on state and local governments to improve planning and zoning practices that will create a more responsive housing supply. It shouldn’t take years (or in some cases, as long as a decade) to go from the initially planning and zoning stages to a completed property.

But that is a debate for a different time. For now, the RBA appears set to take a step in the right direction and finally intervene in the mortgage market. It should’ve been done a year ago -- but better late than never, right?