QE is no silver bullet for Japan's economy

‘Shock and awe' is not a phrase commonly attributed to decisions made by central banks, but last month the Bank of Japan genuinely earned that label when it announced a plan to increase its annual purchases of government debt by 60 per cent.

This was quantitative easing on a level never before attempted. Was BoJ governor Haruhiko Kuroda a genius, or had he lost his mind?

On that question, the jury is still out. As a program it can only be judged in hindsight, after it's had a chance to flow through the financial system and the real economy.

The global evidence on quantitative easing is mixed. Certainly the return on investment has been poor; it took years and trillions of dollars before the Federal Reserve's asset purchases gained genuine traction. It'll be months before we have a clear signal about whether financial markets and the US economy can survive without Fed intervention.

To some extent the global shift towards quantitative easing has been undermined by austerity measures, which have weighed on growth in the United States, the United Kingdom and throughout Europe. Surely these policies work best when combined with expansionary fiscal policy.

The evidence so far on the Japanese version is also mixed, with many commentators declaring it an abject failure. In the September quarter, the Japanese economy dipped into its fourth recession since the beginning of the global financial crisis.

I'm reluctant to declare Abenomics a failure just yet. It's important to remember that we do not know the counterfactual: what would have happened in the absence of quantitative easing? Perhaps, for example, the economy would have experienced a deeper or more persistent recession?

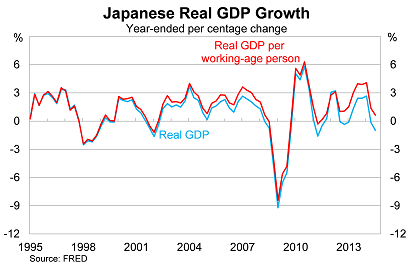

The reality is that the Japanese economy is not doing that poorly. By conventional measures it has been a struggle, but Japan is far from conventional. Both its population and working-age population continues to decline, which weighs on measures such as real GDP even when the more reliable real GDP per working-age person continues to grow.

The graph below highlights the difference between Japanese real GDP and real GDP per working-age person. At this point, the decline in the working-age population is knocking around 1.5 percentage points from real GDP growth annually.

The new program introduced by the BoJ is almost without precedent. On an annual basis it plans to purchase 80 trillion yen worth of Japanese government bonds, up from around 50 billion yen currently. The plan is to push interest rates lower across the entire yield curve, which will lower longer-term real interest rates.

According to the BoJ minutes, “the average remaining maturity of the Bank's JGB purchases will be extend to around 7 – 10 years (an extension of about 3 years at maximum compared with the past)”.

The minutes from the meeting in late October, released earlier today, indicate that there was widespread disagreement over the decision to expand the bank's quantitative easing program. The measure passed on a 5-4 majority vote but some board members expressed concerns that they would be seen to be financing government debt and that the expanded policy may not gain as much traction as when the BoJ introduced the policy last year.

But I'll add another concern. Why expand your quantitative easing program when deflation isn't causing living standards to decline and the financial sector is working adequately? Japan's problem isn't a lack of liquidity, it's a lack of people. Unfortunately conventional monetary policy and measures of economic welfare are rendered useless when population falls.

If Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is genuinely serious about ending deflation and boosting growth, then he should simply open Japan's borders to any young person who wants to go there. Provide financial incentives if need be: it's not as though there isn't millions of unemployed (but educated) youngsters who are fed up with the lack of opportunities in their home country.

Quantitative easing has more than likely supported Japanese growth over the past few years but Japanese authorities are now asking it to defy Japan's demographics. That's a tall order and without a significant upward shift in Japan's working-age population, real GDP growth is likely to remain subdued for the foreseeable future.