Meridian plots a retail powerplay

Last week I caught up with Ben Burge, chief executive of Meridian Energy’s Australian business.

Meridian Energy is a major New Zealand power company but have been involved in the Australian renewable energy sector going back more than a decade, having once owned the Victorian hydro generation system, Southern Hydro. This was subsequently acquired by AGL Energy and was the source of a number of the wind projects AGL has subsequently developed, most notably the largest in the country, Macarthur.

Meridian now is in the process of constructing the 131MW Mt Mercer wind farm near Ballarat in Victoria, and it has several other projects under development.

But much of our conversation focused on Meridian’s launch of its power retailing business in Australia – Powershop.

Burge sees an opportunity in the fact that a large proportion of households are deeply dissatisfied and distrustful of their power supplier, something explained yesterday in 'Why we hate power companies'. Most of the new entrant, smaller energy retailers in Australia aren’t really in the game of doing anything more than being pesky little scavengers who take a little nip out of the big three – Origin, EnergyAustralia and AGL. These upstarts have no clear point of difference or set of assets that provides them with a long-term superior competitive position to those three. They are little more than direct sales operations, really. (Rather than being genuine challengers, their strategy is really to sell out to one of the big three.)

Burge isn’t interested in such a strategy, he wants to do something genuinely different and this is where he feels Powershop can out-compete the big three. For Powershop, the business approach almost comes across a bit like Richard Branson’s Virgin Group ... take on a group of cosy, dominant incumbents with a low cost, simple – with minimal strings attached – offering to customers. It won’t satisfy everyone in the market, but it will cream off a good proportion of quality customers.

At the same time, the idea is to use the dominant incumbency of your competitors against them, outmanoeuvring them with greater nimbleness and a lower cost structure. With incumbency often comes a legacy of systems, assets and business practices which can limit what a company is willing and able to do, and how fast it can respond to change.

For example, if you just spent more than a billion dollars acquiring a government retailer to pick-up a bunch of sticky customers, paying IPART or QCA regulated prices which are way above retailers’ actual costs, then you aren’t too keen on publicising just how shockingly bad those prices are. This might also alert the regulator, in IPART or QCA, to the fact that you have just pulled the wool over their eyes.

It also often means you have legacy IT systems which don’t talk to one another all that well, but which you can’t get rid of because, well, they work. For example, EnergyAustralia, when acquired by TruEnergy, has had a disastrous and costly process of trying to integrate its IT systems. This can hinder an incumbent from rolling out new products and services and making the best use of the internet as a sales and customer service platform.

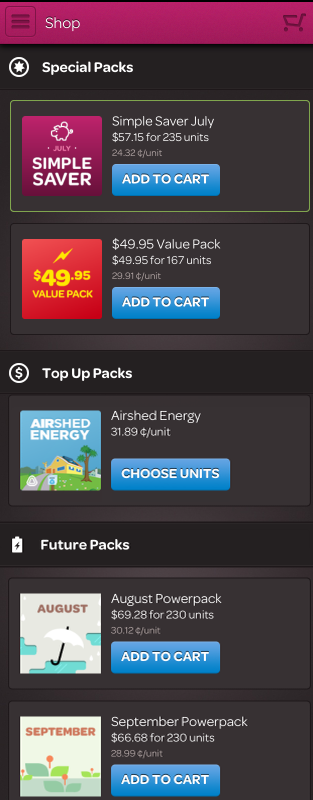

Powershop’s plan is to primarily be an internet-based retailer that won’t seek to lock customers into multi-year contracts. Instead, they’ll almost operate like a little Aussie Home Loans, operating an online shopfront which will offer a market in a variety of monthly power price offers from a range of suppliers, but with Powershop being the underpinning supplier. The graphic below illustrates how the shopfront is intended to operate from a mobile device. So for example, you might be offered in June a special for the month of August from a supplier other than Powershop which, if you buy in advance, is likely to give you a good discount over the standard tariff. In addition, it's possible that a renewable energy project developer could offer a product direct to end-customers via Powershop’s market platform.

Unlike the other new entrant retailer upstarts, Meridian won’t be engaging in door to door sales. Door-to-door selling is probably the most effective mechanism for picking up customers quickly, so it’s a big call to not use such a channel. But it’s also a very costly way to pick up a customer, and almost without exception leads to misled and infuriated customers and members of the community (as salespeople push the boundaries of truth and ethics to persuade customers to sign-up and earn their commissions). A range of retailers – including AGL and EnergyAustralia – have been hauled across the coals by the ACCC for misleading door-to-door sales.

In Burge’s view, by avoiding door to door he’ll end up with a better brand, lower costs of customer acquisition and in fact, a more profitable type of customer. His theory is that a customer picked up from the internet will be more able to self serve themselves, reducing call centre costs. In addition, because he didn’t have to spend a whole lot of money acquiring the customer in the first place, he can afford to not lock them into a multi-year contract. This is likely to be highly appealing to customers who have been burnt by retailers who signed-up them on with juicy discounts but only to hike up prices a few months later.

At present the plan is to focus on Victoria, where the rollout of smart meters that regularly transmitting consumption data provides highly conducive infrastructure for this more flexible, web-based retail offer.