Italy can't blame its recession on the GFC

The eurozone’s third-largest economy has plunged into recession for the third time since the onset of the global financial crisis. Despite a modest recovery across the eurozone, the Italian economy remains vulnerable, with shocking productivity leaving it poorly placed to match the performance of countries such as Germany and France.

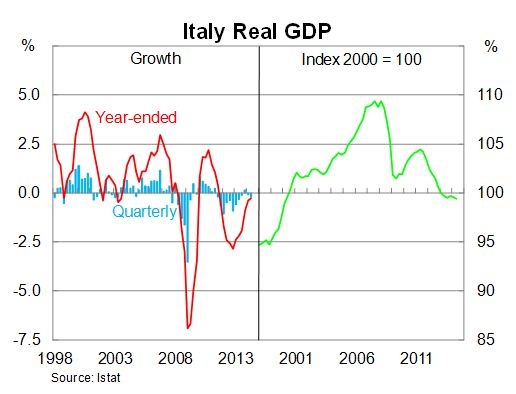

The Italian economy contracted by 0.2 per cent in the June quarter, missing market expectations for a modest gain, to be 0.3 per cent lower over the year. Real GDP has now declined in 11 of the past 12 quarters and is around 9 per cent below its peak.

Technically this marks the Italian economy’s third recession since the onset of the global financial crisis. But given its persistent weakness it is fair to view this as one continuous recession.

The poor first-half result calls into question the government’s official deficit projections for 2014 of 2.6 per cent of GDP. Although softer-than-expected GDP growth will continue to place pressure on tax receipts, the Italian government does not believe Italy will end up with a budget deficit exceeding the European Union’s ceiling of 3 per cent of GDP.

Responding to the ongoing crisis, new Prime Minister Matteo Renzi has announced a range of labour and tax reforms in an attempt to improve growth and productivity. However, so far his efforts have yet to gain much traction. Tax breaks for low-income earners are welcome but a soft labour market and a cautious banking sector are not conducive for a sustainable recovery.

But it would be a mistake to simply assume that Italy’s struggles are merely a symptom of the global financial crisis and sovereign debt crisis. Sure employment would be higher and debt lower if those two crises had not occurred but the Italian economy has been struggling for much longer than that.

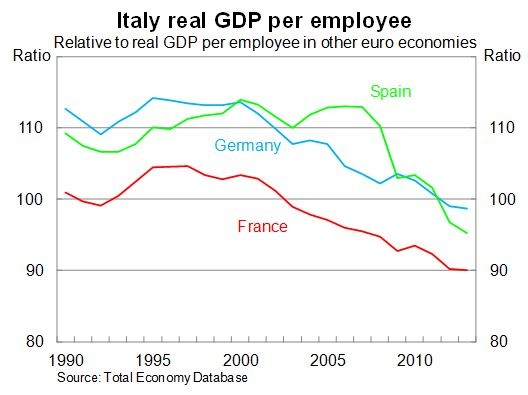

The Italian economy has performed considerably worse than the German, French and Spanish economies since the beginning of the euro.

While Spain has suffered a great deal over the past six years -- and more than Italy has -- its recession came on the back of strong growth over the decade to 2008. The same cannot be said of Italy, where growth was sluggish over the first half of last decade, and real GDP is currently at its lowest level since September 2000.

Identifying why Italy has performed so poorly is easy but understanding the causes is much harder. Essentially Italy has a massive productivity problem, which has persisted for the best part of two decades, and shows few signs of correcting.

The graph below shows GDP per person employed in Italy compared with Germany, France and Spain. A value exceeding 100 indicates that Italy was more productive per employee. Since 2000, Italy’s relative labour productivity has declined by 13 per cent against France and Germany and 16 per cent against Spain.

Total factor productivity -- which measures how effective labour and capital is used together -- has declined throughout the 2000s. Remarkably this has occurred despite strong capital flows into the country following the creation of the euro. At the same time unit labour costs surged in Italy compared with its major trading partners.

Although credit growth has been strong, it has failed to reach productive uses or industries, with the Italian economy investing relatively little in information and communication technology. Compared with Germany and France, management in Italy has been slow to react to a changing work environment.

Some right-wing commentators are happy to attribute the eurozone’s woes to labour market protections -- which can limit labour mobility and reduce productivity -- but according to the OECD, Italy has a less rigid labour market than either Germany or France and has reduced employee protections considerably over the past two decades.

The eurozone is full of sad tales of mismanaged economies but the Italian story is somewhat unique. Spain, for example, has suffered a great deal over the past seven years but its pain will only be temporary; once it has successfully unwound its debt burden, its recovery will gain traction and the labour market will improve.

The road ahead for a country suffering a two-decade productivity decline is far less clear and more difficult to fix. The Italian economy is in desperate need of business reform, and while Prime Minister Renzi is making the right noises, if businesses fail to improve the quality of their management and resource allocation then any reforms will be for nought.