How to survive the assault on savings

Corporate treasurers and others with large cash holdings have watched the walls close in around them for years. It is only in the past couple of months, however, that their gradually disappearing room for manoeuvre has turned into a suffocating constriction. So begins the 'big squeeze': the European Central Bank's engineered assault on savings. Pushing back against those walls is futile, but we believe there is a way for investors to escape this stranglehold on cash and breathe a little easier.

Traditionally, there have been two primary investment vehicles available to store cash: money market funds and bank deposits. Both eliminate mark-to-market volatility, removing uncertainty associated with market gyrations via a fixed net asset value structure. This is a great benefit for anyone who has better things to focus on than the daily price fluctuations of their cash.

Unfortunately, we believe neither vehicle is fit for this purpose any longer.

Money market funds

We believe it is only a matter of time before yields on MMFs dip into negative territory. Many MMFs have maxed out the risk they can take; still yields are just a few basis points above 0 per cent.

As the ECB expands its balance sheet, excess reserves in the banking system will increase and could eventually push money market yields down toward the floor established by its deposit rate, currently at -0.20 per cent (as my colleague Andrew Bosomworth detailed in his December 2014 Viewpoint, “The ECB's Shifting Regimes”). If that happens, MMFs will technically “break the buck”, eroding capital day by day. In effect, savers will pay for the privilege of lending, getting back less than they put into such funds. In our opinion, this potential loss of capital is an automatic disqualifier as a 'safe' store of value.

The even bigger concern, however, is the very survivability of European-domiciled money market funds. Over the past five years, the industry has shrunk by 40 per cent, and new European regulations, set to be voted on next year, could accelerate the trend toward extinction. The European Parliament was set to pass a set of MMF regulations in March 2014 that would have dealt a mortal blow to the industry, essentially making money market funds too unprofitable to run, and far less attractive for investors.

Fund providers would have had to invest 3 per cent of their own capital in order to run money market funds, something nearly no asset manager is willing (or able) to do. And investors would be subject to gating, limited withdrawals during times of stress, something that runs against the very purpose of money market funds.

The European Parliament's vote was pulled at the last minute in the hope that a successor bill, to be voted on by a future parliament, will be watered down. It may not be. Therefore, if for no better reason, cash holders may want to establish a contingency plan now in case their MMFs may no longer exist in a few years.

Bank deposits

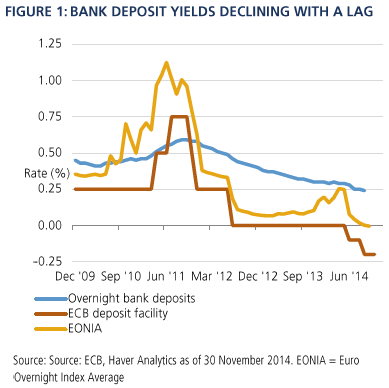

What about bank deposits? Although they continue to offer investors a healthy spread over MMF yields, returns are rapidly declining, with a lag (see Figure 1).

According to an article in The Economist, aptly titled “Saving in Germany: Worse than nothing” (November 8), a regional bank in Germany recently began charging negative yields for large depositors. The longer money market yields remain near zero or go negative, the more common this could become.

Again, however, the bigger concern with bank deposits stems from new regulations. Take, for example, the European Union's new bank resolution regime, set to be implemented in January 2016, with some member states opting to be early adopters. The statute prohibits governments from providing deposit guarantees as they have done in the past. Under the new rules, if a bank gets into trouble, it must first bail-in subordinated and senior creditors, including large depositors, before it is allowed to access official government support. Put another way, the counterparty risk that large depositors face is about to soar. For this reason, expect to see rating agencies continue to issue waves of quality downgrades for European banks in coming quarters as these banks lose what the rating agencies call “government uplift”, the increase in creditworthiness that resulted from implicit government backing in times of emergency.

The not-so-great escape

There is, however, a way to escape the big squeeze. It involves a little extra effort from cash holders, but not much.

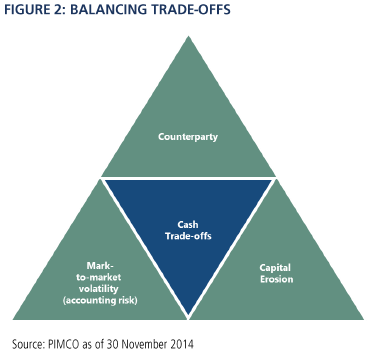

Most cash holders have traditionally prioritised the elimination of mark-to-market volatility, followed closely by reducing counterparty risk, to the exclusion of other considerations. However, today's low-yield, regulatory-overhauled landscape demands a reassessment of this balance of trade-offs. Not only will the counterparty risk of bank deposits rise, a third consideration has surfaced that has not existed before: capital erosion owing to negative interest rates.

By stepping out of traditional cash management vehicles and into floating net asset value portfolios, admittedly permitting some degree of mark-to-market volatility, corporate treasurers may be able to limit capital erosion, potentially a much bigger concern, while still remaining focused on reducing counterparty risk (see Figure 2).

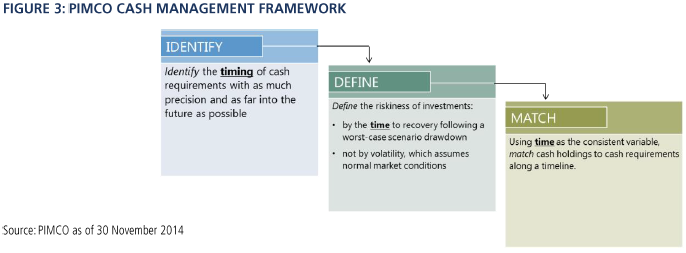

At PIMCO, we have a rigorous framework for balancing these three trade-offs -- mark-to-market volatility, counterparty risk and capital erosion -- that we employ for our own portfolios, and for many of the largest corporate treasury departments in the world (see Figure 3).

- The first step involves projecting cash requirements over time. While most cash may be held for precautionary purposes, some treasurers have clarity over future cash requirements that extend out months, if not years. This can be exploited.

- Second, we define a set of investments, not in the traditional sense but with a conservative definition of risk: assessing how long it could take for the investment to recover following a mark-to-market drawdown under the worst case scenario. PIMCO's deep experience with quantitative research, analytics and systems for modelling risk have long been employed in an effort to manage risk in our portfolios, and can help clients to understand the risk in their portfolios and identify investments that may be appropriate for all types of projected cash requirements (as defined above).

- Finally, we map these investments along a timeline that matches projected cash requirements.

To summarise, our framework is a methodical approach to balancing the three trade-offs: mark-to-market volatility, counterparty risk and capital erosion. The goal is to limit counterparty risk and reduce the threat of capital erosion, offset by a risk-managed increase in mark-to-market volatility.

Breathe easy

We realise this might represent outside-the-box thinking for some. The alternative is to remain boxed in without breathing space by the ECB and other financial regulators.

© Pacific Investment Management Company LLC. Republished with permission. All rights reserved.