Empty-nesters locked up with their money

The still-booming house price figures released by RP Data yesterday will be welcomed by the thousands of investors who have piled into the market in past months.

The survey showed prices up 4.2 per cent nationally in the three months to August, with Melbourne at 6.4 per cent and Sydney at 5 per cent.

It's not only investors that will be happy. Many home owners see their primary residence as a buffer against hard times, a source of equity withdrawal when money for new projects is required and as a large bequest to the next generation -- usually their offspring.

Parents often say they want to leave their children better off then they themselves were, and traditionally the capital gains tax-free primary residence was the main vehicle for passing wealth between generations.

However this pattern looks set to change. There is a growing tension in the economy between a generation holding housing assets 'for their children' and the same generation's increasing demand for pension, health care and services that are funded by taxes paid by those same 'children'.

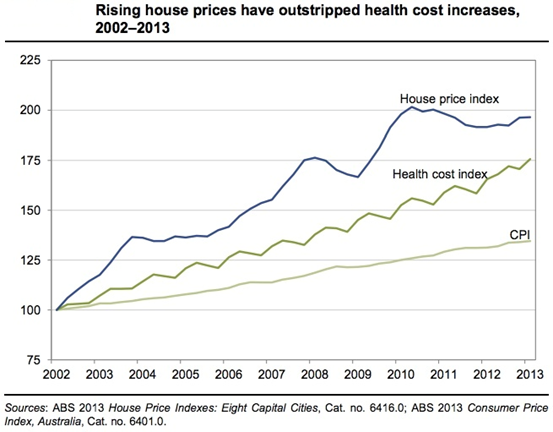

To illustrate the point, the Productivity Commission last November prepared a chart showing the divergence between house prices, health costs and inflation (see below).

For the children of retiring baby boomers, then, a perverse situation is arising in which it looks impossible for the federal government to deliver tax relief to families while balancing the budget at the same time.

In fact the Abbott government is making life tougher for many young families, accompanied by the message 'the age of entitlement is over'.

However many young taxpayers are aware that their parents are sitting on large fortunes, locked up as housing wealth, that will be theirs in 30 years' time.

That, to paraphrase a vivid colloquial description, is a sandwich with a pungent and unappetising filling.

In effect, the message is: work hard and pay extra tax while your children are young, and be rich when your bones ache too much to enjoy the money.

The problem is being repeated throughout the developed world, according to a study released on Friday by The New Zealand Institute, a think tank led by long-time Business Spectator columnist Oliver Marc Hartwich.

The report, entitled 'Empty nests, crowded houses', argues that around the world the housing market is one of the most distorted markets there is.

The types of dwellings built, and their locations, are determined by planning authorities who are often out of step with the needs of the people who will occupy the homes they approve.

And worse, tax and retirement savings laws usually distort the market even further.

In the UK market, for instance, the ageing population features an ever-increasing population of 'empty nesters' who, even if they wished to find smaller, more appropriate dwellings, face a series of obstacles that make it all too hard.

The report notes: "The current UK housing affordability crisis is not principally because of a lack of housing, but the way the tax system has created perverse incentives.

"The tax system encourages under-occupation of housing. What is needed is a tax system that better balances income taxes and wealth-related taxes, and reflects the social costs of the over-consumption of housing."

That problem is mirrored in Australia, but is a difficult area of public policy to confront as any attempt to do so is greeted with "it's my money, and I'll live in any house I choose!"

Quite right. This author, like most Australians, reserves the right to do 'irrational' things with his money. (Just last week I bought a kelpie.)

But policy that forces empty-nesters out of their homes is not the issue -- 'forcing' people to stay in large dwellings is what the New Zealand study is more concerned with.

Given the sustained house-price run-up of the past 20 years, many retirees now find themselves in homes worth, say, $700,000.

While that money sits there, it is a giant nest egg to bequeath to the next generation, and its capital gains are tax-free.

Moreover, if the home owner has only modest other assets, including modest superannuation income, the value of that home will not affect their right to claim a pension from the government.

Meanwhile, down the street, a family of four might be squeezed into a two-bedroom townhouse worth $500,000.

However, if the retirees wished to sell up and move to a similar townhouse, $200,000 of their assets would now be back in play -- reducing their pension income, and possibly incurring a tax liability.

So let's be clear. Avid gardener Granny Smith has a perfect right to stay in her large home, with a large garden, if that's what she wants. But Granny Jones next door, who hates gardening and maintaining a large house, may be kept in situ by the "perverse incentives" that the NZ study discusses.

As the Productivity Commission put in a report last November: "The treatment of home assets in pension eligibility tests and the barriers to accessing home equity (particularly transactions costs, such as stamp duty on property) are likely to play a major role in this pattern."

This is an area of policy reform that is moving far too slowly.

The PC report examined the "evidence on the viability of one possible avenue for funding age-related costs -- tapping the otherwise inactive wealth held in the housing assets of older Australians" and made politically cautious statement that "while the adoption of such a policy approach is currently over-the-horizon, it is nevertheless worth deeper consideration".

One serious issue that will arise when (or if) a federal government has the courage to tackle this problem is the effect it will have on the value of larger homes. An increased number of large homes offered for sale could dent the value of those homes.

That's bad news for the size of the bequest Granny Smith leaves to her descendants, but good news for families living in crowded houses.

Viewed from another perspective, many young families will wonder why their taxes fund a pension for Granny Smith, whose only major asset is the family home, when all the capital gains tax forgone on that asset will flow to her descendants.

There was a lot of debate in the media last week about superannuation tax concessions that are worth about $30-$40 billion to the federal budget before offsetting pension savings are taken into account.

But that major 'tax expenditure', as it is known, is the smaller part of the total 'tax expenditures' figure in the budget. The Productivity Commission report notes: "Tax expenditures represented $111bn in forgone revenue in 2011-12 (Treasury 2013), of which tax concessions on housing and superannuation are the most important."

It really is hard to think of a more distorted market. The political pressure to reduce the 'perverse incentives' in housing will only build until governments act.