Does WA care about Shorten's jobs crisis?

Both Prime Minister Abbott and opposition leader Bill Shorten have been pressing the flesh out west in past days, desperate to clinch effective control of the senate via the WA senate by-election.

The final result of that election will decide who has the upper hand in the battles ahead over issues such as the carbon and mining taxes.

By Saturday evening, we should know in rough terms which of their very different pitches has hit the right note with voters.

The Coalition is trying to convince voters that without the burdens of the carbon tax, mining tax and oodles of red-tape, the Australian economy will take off as a “diverse powerhouse economy that will create one million jobs over the next five years and two million jobs over the coming decade”.

Heady stuff and, for once, full of optimism.

Labor, by contrast, is happy to base its campaign on fear. Its pitch is all about preserving jobs, particularly related to the areas of government in which the Coalition’s commission of audit will, supposedly, recommend ‘savage’ cuts.

Voters are being asked to weigh the Coalition’s rather sketchy plans for growth against Labor’s fears of continuing job losses across the nation.

While these are not the only issues in play, at this time in Australia’s economic evolution the jobs issue is paramount. Time is short to create jobs in sectors such as agriculture, tourism, services exports and advanced manufacturing to replace jobs in the cooling resources sectors.

But can it be done? Economist Ross Garnaut set out the enormity of the task in his book ‘Dog Days’, which he finished writing just after the Abbott government was elected last September.

Garnaut argues that an inflection point in our stellar economic trajectory was reached in late 2011, and that neither major party (nor any of the small ones come to think of it) has policies to turn us into anything like an ‘economic powerhouse’.

That inflection point was a reversal in our terms of trade. The resources industries had, up to that point, extracted ever-increasing prices for the commodities we sold to the world, making the prices of the things we wanted to buy from abroad (particularly manufactured goods from China) relatively cheaper year after year.

With coal prices coming off significantly already, and with the likelihood of iron ore following, Garnaut thinks the only way we’ll sell things to the world is to have a “real depreciation” of the currency.

By that he means that not only does the dollar need to fall, but that prices and wages in Australia must remain constrained if we are to become competitive with the world.

In essence, we paid ourselves too much during the boom years and will, as a nation, have to take a pay cut now that we’re not flavour of the month.

Neither major party likes this thesis. It is almost impossible to communicate to the electorate without losing votes, so both sides have an interest in arguing that Garnaut is dead wrong.

Coalition MPs have, to an extent, come to believe their own PR. The argument Abbott took to the 2013 election was that the ‘capex cliff’, which will see mining investment, which peaked at 8 per cent of GDP, decline rapidly in the years ahead – could be offset by an investment surge in other sectors.

Well it’s a good story, and Australians, who are richer than they’ve ever been, want to believe it.

Meanwhile, Labor MPs argue that the capex cliff won’t change things all that much. They have to tell that story, as they want any ensuing fall in Australians’ standard of living to be pinned on the Abbott government.

In truth, neither the run-up to the peak of the investment boom, which helped Labor, nor the corresponding fall in investment, were much within the control the federal government.

Our main customers – especially China – cranked up demand, and our terms of trade, and affluent lifestyles, followed.

So where does this leave WA, and more particularly, where does this leave the Abbott and Shorten messages to voters in that resource-rich state?

The first thing to note is that at a national level, we do indeed have a problem with job creation. As Callum Pickering has explained, the promise of “one million jobs” is actually not too impressive by past standards (The shaky foundations of the Coalition's 'powerhouse economy', March 31).

We need more jobs to keep up with population growth, and the headline unemployment figures simply fail to capture the real jobs situation.

As Gary Morgan of Roy Morgan research points out, repeatedly, the ABS measure of 6 per cent unemployment does not reflect underemployment – if you have at least one hour of work, you’re employed! Nor does it reflect those who’ve given up looking for work, though they are captured by the participation rate.

So Morgan’s February jobs survey says: “In February 2014 an estimated 1.561 million Australians (12.3 per cent of the workforce) were unemployed – the highest rate of unemployment for 20 years since February 1994 (12.3 per cent).”

Nasty, but Garnaut’s preferred measure of unemployment accords with Morgan’s survey.

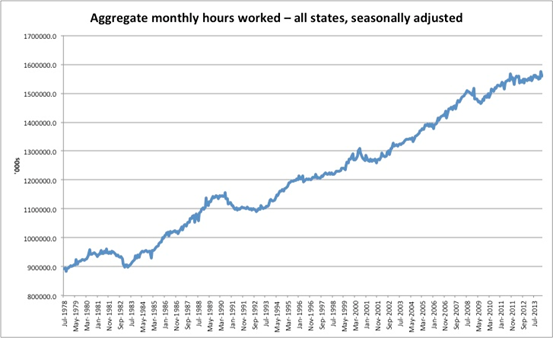

Garnaut focuses on aggregate hours worked. In times of economic downturn there is a clear dip in total hours worked, as employed staff have their hours cut, sacked workers sit at home, and jobless workers give up looking for work altogether.

In the chart below, based on seasonally adjusted ABS data, the big recession of 1990 to 1991 shows up as a clear dip. So too do the 1981-83 recession, the dotcom crash in early 2001 and the Lehman Bros event in 2008.

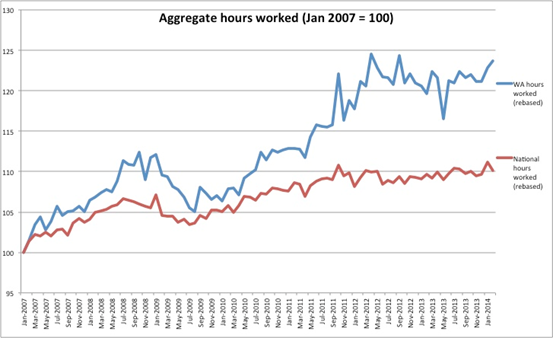

What has Garnaut worried, if not the politicians, is the flattening of the ‘hours worked’ data, which is much more clearly seen on the chart below. Taken in aggregate, the national hours-worked figure (the red line) is virtually flat for two years (though the population kept growing at trend).

WA, however, is quite a different story. The blue line below shows that while the thousands of job losses in the eastern states have hit the hours-worked data hard, in WA workers have continued to benefit from the resources-driven flow of wealth.

In passing, it’s worth noting that WA’s population has grown 20 per cent in the past seven years, while the national population figure has risen only 12 per cent.

Nonetheless, the stark difference between the growth in hours worked in WA, and in the country as a whole stands – Abbott and Shorten have left rust-belt states with depressed labour markets, to fly to a state where the good times are mostly still rolling.

Sources on the ground tell me Western Australians are not totally sanguine about job security – but they are more relaxed than the denizens of South Australia, Victoria, New South Wales and Tasmania.

This may well work in Tony Abbott’s favour on Saturday. If there is one place the ‘million new jobs’ argument will hold sway, it’s WA.

Conversely, Shorten may have a hard time convincing sandgropers that bad times are just around the corner.

That message, though slowly sinking in across Victoria and NSW, will take a year or two longer to mean anything out west.