Diary of a self-funded retiree: Entry 7

Welcome to the seventh update in my retirement journey diary, where I'm sharing how my wife and I are planning for the transition into retirement. Here's what I've covered in my previous entries:

-

Entry 1: How we've simplified our financial lives

-

Entry 2: Our investment strategy and asset allocation both now and in retirement

-

Entry 3: Our retirement budget, including how we plan to adjust our spending if markets shift

-

Entry 4: Downsizing, aged care, and how much to give the kids (and their kids)

-

Entry 5: How we plan to stay healthy and keep our minds active in retirement

-

Entry 6: What it takes to run our SMSF

Diary entry 7: How we're managing risk in retirement and making sure we don't run out of money

In this entry, I look at the risks of investing in retirement, why market timing becomes important and how to deal with FORO - the fear of running out. This is probably the biggest worry my wife and I have about our retirement.

Why is market timing in retirement important?

Our Chair - Paul Clitheroe - has several simple pieces of advice that we follow at InvestSMART. One of them is "time in the market is more important than timing the market."

For most of your investing life, that's true. Retirement is different, though, because you're no longer just investing - you're also drawing money out. If markets fall early in retirement and you have to sell at low prices, those assets can't recover when markets bounce back. That's why timing matters more when you retire.

This is known as sequencing risk - because the order in which markets rise and fall can make a difference to your outcome. Two retirees with the same average return can end up with very different balances depending on when the ups and downs happen.

Most investors know about dollar cost averaging, where you invest regularly whether markets are up or down. You buy more shares when markets are low and fewer when they're high, so your average purchase price evens out over time.

Retirement reverses that - you withdraw regularly whether markets are high or low, which means you can end up selling at the bottom.

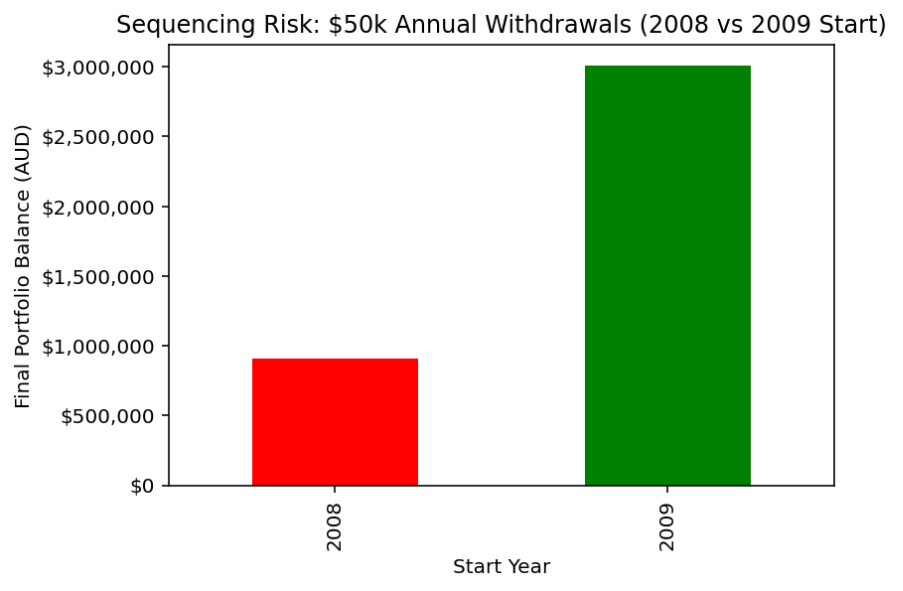

The example below shows what happens over 15 years if you start with $1 million, invest only in Australian shares and withdraw $5,000 a month. Starting your drawdown in 2009 instead of 2008 would have left you almost $2 million better off at the end.

It's an extreme example because 2008 was the height of the GFC, but it highlights sequencing risk clearly.

Why can't we just go defensive?

One way to avoid sequencing risk altogether would be to put all our money into term deposits earning 3% to 4%. We'd certainly sleep better at night, but in about 25 to 30 years our standard of living would be much lower because of inflation.

As I mentioned in a retirement webinar a few months ago, we need some growth assets to at least maintain our spending power. The things we're likely to spend more money on in later life, such as healthcare and insurance, tend to increase more than headline CPI numbers.

To put it in context, using the earlier example of drawing a $50,000 pension each year, that $50,000 would only have the spending power of about $29,000 after 20 years - a drop of more than 40%. Holding growth assets helps offset the impact of inflation.

FORO - the fear of running out - and what we're doing about it

Something else we worry about is running out of money before we die. The average age at death for someone who is 65 now is 85 for men and 88 for women - but half of people will live longer than that. That's why we're planning for at least 30 years in retirement.

There are some (partial) solutions to make sure we have a reliable semi-inflation-proof cashflow from our super, regardless of market volatility. I use the term "cashflow" because I think it's important to rely on asset growth and asset income in retirement - there is no tax on income or capital gains when you are in pension mode, so you should make the most of both.

We hold a mixture of growth and defensive assets so we should get growing capital (and income) as well as some stability in times of market volatility. Most commentators suggest moving to more defensive assets as you get older - for example, moving from 60:40 growth versus defensive at 65 to around 30:70 in your 80s and even more in your 90s.

Our portfolio is currently 70% growth and 30% defensive, and we think we'll stay with that mix for a long time.

The table below shows the difference in your end balance after 20 years with a 50:50 portfolio versus 70:30 mix. It's based on a $1 million starting balance and $5,000 a month in drawdowns, increasing with inflation (2.5%) to around $8,200 a month after 20 years.

|

Start date |

End date |

Ratio |

|

|

50:50 |

70:30 |

||

|

1/07/1990 |

30/06/2010 |

$2,625,226 |

$2,453,163 |

|

1/07/1995 |

30/06/2015 |

$1,721,751 |

$1,978,980 |

|

1/07/2000 |

30/06/2020 |

$881,383 |

$999,252 |

|

1/07/2005 |

30/06/2025 |

$575,958 |

$732,126 |

This is a simple comparison using Australian shares for growth and Australian bonds for defensive assets. Including property exposure would change the results.

We know that we'll have more left after 20 years by holding growth assets, however, the table also highlights how overall returns have diminished from all assets since the 90s and early 2000s. We expect the returns for the next 20 years may be lower.

How about annuities for retirement income?

We also looked at whether annuities might fit into our plan. Standard annuities pay a fixed amount each month until the capital is used up, usually over a term of up to 15 years. With lifetime annuities, the issuer guarantees to pay you the same amount until you die, usually at a lower rate. You can also buy inflation-linked annuities, where payments rise with CPI. Payments from an annuity purchased with super after age 60 are tax-free.

The drawback is that annuities usually offer lower returns than you can get from the market over the long term, and adding the lifetime and CPI components will reduce your initial payments substantially.

We think we can get a better result by managing the money ourselves, so we've decided annuities are not right for us.

What can we do to stop running out of money?

One way to give our retirement savings the best chance of lasting is to continue working part-time. This won't be an option for everyone, but luckily, I can. Any extra income delays when we have to start drawing down on our pension pot.

If our savings do start to run low, we can also adjust our spending. We've done our budgets and broken our spending into what we have to spend and what we'd like to spend. If hard times come (and they probably will), we have a good idea of what we can cut quickly.

The age pension is also a fallback. It's set at a low level and is really designed as a final safety net. If we do run out of savings, we won't starve, but our lifestyle would change dramatically.

My top tips

-

Plan for a long retirement - half of us will live beyond life expectancy.

-

Keep some exposure to growth assets so your spending power keeps up with inflation.

-

Review your risk levels more often when you retire.

-

Consider using annuities for some of your retirement income, though you're potentially locking in lower returns.

-

Have a plan for market downturns, such as cutting discretionary spending quickly. Markets always recover but it can take some time.

What's next?

Next time I'll share our thoughts on living overseas for extended periods, and where we think aged care might be more affordable.

You can read entry 6 here. Diary entry 8 will be published on 5 February 2026.

Frequently Asked Questions about this Article…

Sequencing risk is the danger that the order of market returns (especially big falls early in retirement) can seriously reduce your portfolio because you’re withdrawing money while markets are down. Two retirees with the same average return can end up with very different balances depending on when gains and losses occur. The article gives a stark example: starting a $1 million drawdown and withdrawing $5,000 a month in 2008 versus 2009 would have left you almost $2 million better off after 15 years, highlighting how timing of market drops matters in retirement.

Retirement changes the rules — timing matters more because you’re taking regular withdrawals. While the long‑run investing rule is 'time in the market' (as InvestSMART’s Chair Paul Clitheroe reminds us), retirees face sequencing risk that can make poor early timing very costly. Rather than aggressive market timing, consider drawdown strategies, a mix of defensive and growth assets, and planning for downturns so you’re less forced to sell at low prices.

There’s no one-size-fits-all split, but the article outlines common guidance: keep enough growth assets to protect spending power from inflation, and gradually move to more defensive assets as you age. Many advisers suggest moving from around 60:40 (growth:defensive) at age 65 toward 30:70 in your 80s and higher defensive exposure in your 90s. The author’s portfolio is 70% growth / 30% defensive and they plan to stay there for a while — a choice that helped outperform in some historical 20-year periods, but past performance varies by timeframe and asset mix.

Putting everything into term deposits or cash removes sequencing risk but creates a different risk: inflation erosion. The article notes term deposit rates around 3–4% would make you sleep easier short term but could sharply reduce your standard of living over 25–30 years. For example, a $50,000 pension today could have the spending power of roughly $29,000 after 20 years if not protected against inflation, so many retirees keep some growth exposure to preserve purchasing power.

Annuities can provide reliable income — fixed, lifetime, or CPI‑linked options exist and payments from an annuity bought with super after age 60 are tax‑free. However, annuities generally pay less than potential market returns, and adding lifetime guarantees or inflation indexing reduces initial payments further. The author considered annuities but decided to manage the money themselves because they felt they could get a better result; annuities remain a trade‑off between certainty and potentially lower income.

Plan for a long retirement (the article plans for at least 30 years), keep a mix of growth and defensive assets to support income and capital growth, and build contingency options: work part‑time to delay withdrawals, split your budget into essential and discretionary items so you can cut quickly if needed, and remember the age pension exists as a final safety net. Regularly reviewing risk levels and having a clear cashflow plan also helps reduce FORO.

Have a defined plan before downturns hit: set aside defensive reserves to avoid forced selling, review and adjust your risk level more frequently in retirement, know which discretionary expenses you can cut quickly, and consider partial income solutions (like part‑time work or targeted annuities) if suitable. Markets recover over time but recovery can be slow, so planning ahead limits the need to sell at low prices.

Plan for a long retirement — the article points out average age at death for someone who is 65 is about 85 for men and 88 for women, but half live longer, so planning for 30 years is sensible. A longer timeframe increases the need for some growth assets to keep up with inflation (especially rising costs like healthcare) while also requiring strategies to manage sequencing risk, such as a balanced asset mix and contingency spending plans.