Could quantitative easing happen in Europe?

At the April 2014 European Central Bank press conference, ECB President Mario Draghi said that the ECB’s Governing Council had unanimously agreed that unconventional measures, including quantitative easing, could be used to cope with risks of a too-prolonged period of low inflation.

As my colleague Andy Bosomworth detailed in his February 2014 Viewpoint, “Flirting With Deflation”, eurozone inflation has been well below the ECB’s target of “close to, but below 2 per cent” for some time. Core inflation has been at or below 1.5 per cent for almost two years, and below 1 per cent since October 2013. Since the start of 2014, headline inflation has fallen sharply and sits dangerously close to zero at only 0.5 per cent in March, according to ECB data. The ECB forecasts inflation to remain well below its target into 2016. With such an outlook, investors could be forgiven for thinking that the risks of prolonged low inflation abound and that QE is imminent.

We, however, expect the ECB to be more patient. Past behaviour demonstrates that the hurdles for QE are clearly higher in the eurozone than elsewhere. This note focuses on what might trigger unconventional ECB easing, when it may happen and how to position for it today.

Sequencing matters: expect ECB to exhaust conventional arsenal first

In the Q&A session to April’s press conference, Draghi made it clear that the ECB has not yet extinguished its conventional tools. Given the technical and political difficulties with unconventional tools, we would expect the ECB to first extinguish its conventional measures before initiating unconventional measures.

The pros and cons of the various unconventional measures have been studied in great detail by ECB staff, and are worthy of a separate note. Cuts in the main 0.25 per cent repo rate and changes to the ECB’s liquidity operations, for example abolishing the Securities Markets Programme tender, clearly stand in “conventional” territory. Asset purchases, on the other hand, either QE via government bond purchases or credit easing via purchasing private assets, are clearly unconventional. We would also argue that negative deposit rates and radical changes to ECB liquidity provision, for example via a new super-long fixed rate repo (the ECB’s long-term refinancing operation), also fall in the unconventional field.

Inflation: the key economic variable to watch

The ECB and the consensus alike were surprised by the sharp fall in inflation last year, and this in turn led to a policy rate cut in November 2013. Although low inflation is a global phenomenon, matters have been exacerbated in Europe by a combination of peripheral cost-cuts and the absence of strong German domestic demand to take up the slack.

Today’s expectation is that inflation will mean-revert back to 2 per cent; but the period of subdued sub-1.5 per cent inflation is much longer than in the past. In March this year, the ECB staff forecast that inflation will average 1 per cent in 2014, 1.3 per cent in 2015 and only reach 1.5 per cent in 2016. Today’s economists’ consensus is similar. We think that a clear trigger for unconventional ECB easing would therefore be if inflation, rather than rising, fell closer to zero percent.

At first glance, Eurostat’s flash March 2014 inflation estimate suggests this has already happened. Headline inflation fell to 0.5 per cent year-over-year from 0.71 per cent in February this year, while core inflation fell to 0.8 per cent from 0.99 per cent over the same period. Inflation of 0.5 per cent is probably low enough to trigger unconventional measures, but not if it is due to one-off effects. March’s fall in headline inflation probably owes more to the timing of Easter price hikes: In 2013, Easter was in March, but it falls in April this year. We expect headline inflation to bounce back to around 0.8 per cent in April as these base effects reverse. Such a bounce-back would probably deter the ECB from implementing unconventional measures in the next couple of months.

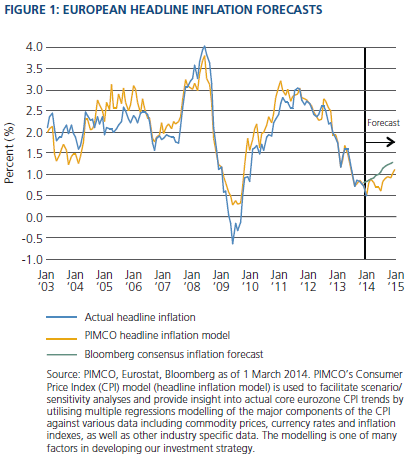

A more likely trigger for unconventional easing is that inflation rises more slowly than the ECB expects. Our assessment of recent commodity prices, in combination with Europe’s focus of recovering peripheral “price competitiveness” solely through cutting costs, suggests that inflation will remain stuck near 0.75 per cent for the next six months, rising slowly to less than 1 per cent in Q4 2014. The ECB and consensus forecast implies a slightly higher path of inflation: Bloomberg consensus forecasts 0.9 per cent in Q2, 0.9 per cent in Q3 and 1.2 per cent in Q4 2014 (see Figure 1).

Sticky inflation, over the next few months, could lower the ECB staff’s 2014 inflation forecast and may result in further easing of conventional policy. But unconventional easing will probably require more data. Unless inflation falls further, which is not our expectation, markets will probably have to wait until Q4 2014 before the data either supports or rebuts the ECB’s 2015–2016 inflation outlook.

Inflation expectations: slower moving but clear trigger for action

Anchored inflation expectations are the crucial element on which economists base their forecast of gradually rising eurozone inflation. A fall in inflation expectations would therefore be a clear trigger for unconventional easing.

The ECB frequently notes that inflation expectations are well-anchored near 2 per cent. The ECB places significant weight on the long-term inflation forecast from its own quarterly Survey of Professional Forecasters. However, by its very nature, this slow-moving survey will lag any changes in market, consumer and corporate inflation expectations.

At the other extreme, market prices of break-even inflation change rapidly, but are more likely to give the ECB an early signal of falling inflation expectations. Market break-even inflation rates reflect the market’s estimate of future inflation plus a risk premium. As such, break-even rates have historically estimated a higher level of medium-term inflation than analysts.

The five-year break-even inflation rate (starting five years forward) is the best proxy for medium-term market inflation expectations as it strips out short-term inflation volatility created by the economic cycle and energy price shocks. So far, these expectations have remained relatively stable (see Figure 2).

But market expectations of short-term inflation have fallen dramatically. At current levels, the market expects inflation to average around 1.2 per cent over the next five years. When viewed in discrete annual inflation rates, the market is pricing inflation to rise very slowly, only surpassing 2 per cent after seven years!

Falling inflation could clearly drag short-term inflation expectations lower. But the absence of reflation over 2014 could also drag longer-term inflation expectations lower. Investors should therefore closely watch forward break-even rates for any signs that eurozone inflation expectations are becoming de-anchored.

Growth slowdown: a low probability, but a clear spark for ECB action

Given that economic output is still 2.5 per cent below its Q1 2008 peak, the ECB’s forecast is for a very weak recovery. ECB gross domestic product growth forecasts of 1.2 per cent in 2014 and 1.5 per cent in 2015 are very similar to consensus. These growth rates are only just above most estimates of potential growth: The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development forecasts potential growth of 1.2 per cent in 2015, and the eurozone’s 18-year average growth rate is 1.4 per cent. If growth were to slow, we would expect the ECB to respond with unconventional policies to offset the disinflationary impact.

But the high frequency data suggests this is a low probability. Quarterly GDP growth accelerated to an annualised 0.9 per cent in Q4 2013; high frequency data suggest that quarterly growth is running at about a 1.5 per cent annualised rate. If maintained, this would be consistent with a small upward revision to the ECB’s GDP forecasts. The bottom line is that a negative growth shock is required if lower ECB growth forecasts were to be the cue for QE.

One last thing: stress tests

The ECB stress tests scheduled for Q4 2014 may also influence the timing of any ECB unconventional measures. Strictly speaking, these stress tests are designed to ensure that the ECB assumes its financial supervisory role with a cleaned-up banking system. But there will be a positive feedback loop between any unconventional ECB measures and the price of assets on European banks’ balance sheets. The ECB may prefer to wait until after the stress test to avoid any accusations that unconventional measures are targeted at improving the health of European banks.

Positioning for the possibility of unconventional ECB action

Unusually, the ECB may embark on additional unconventional measures at a time when the US Federal Reserve is winding down its QE program. Investment strategy therefore needs to weigh not only the probability of unconventional ECB action and the potential asset price upside, but also the assets’ correlation with other global risk premia.

The scale and scope of any unconventional action will determine the size of the market impact. Some forms of unconventional policies will also be more effective than others. But the effect would be similar if the ECB introduced negative deposit rates, purchased assets or provided ultra-long liquidity at fixed rates to European banks.

Initial interest rate cuts or liquidity injections would lower overnight interest rates and encourage investors to move out along the interest rate curve. Growing evidence of reflation could then see interest rates move higher. Currently, low Bund yields, and their positive correlation with the US bond market, mean we would need a higher probability of QE to argue for a large duration position today.

The same argument holds for the euro exchange rate. We would need more certainty that QE was imminent to expect the euro to weaken in the face of continued portfolio inflows, a current account surplus and a steady stream of comments from US central bankers.

Assets with a high degree of eurozone risk premia appear more attractive. And while peripheral spreads are not as cheap as they were in January this year, they are still attractive versus other eurozone corporate credit risk. Spain and Italy remain our preferred sovereign holdings: They are systemic credits and their economic challenges, although significant, are less than in the smaller peripheral sovereigns.

European banks also offer good value. The ECB’s Asset Quality Review has already resulted in many banks raising capital. And banks’ balance sheets benefit from eurozone reflation. We prefer the subordinated part of core eurozone banks’ capital structure as we find senior debt more attractive in US and UK banks. Non-financial bonds would also probably benefit from any unconventional measures. However, Solvency II-related demand from European insurance companies has made core eurozone non-financial credit valuations less appealing than peripheral sovereigns and banks.

Myles Bradshaw is is an executive vice president and portfolio manager in Pimco's London office. © Pacific Investment Management Company LLC. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.