Cheap imports? How about no imports?

Underlying the debate over whether the Abbott government should have continued to prop up Holden is the growing addiction of Australian consumers to cheap imported goods. Electronics, cars, whitegoods, clothes, footwear – you name it.

When former Hawke/Keating minister Graham Richardson wrote in yesterday’s Australian that “there must be something we can make here that has a future on global markets”, the implied urgency was that we can’t keep importing our current lavish lifestyles if we don’t maintain our exports. (Richo, for instance, might not be able to drive his beloved Lexus 250.)

A healthy domestic economy is fine. However, if it does not manufacture sophisticated ‘things’, it must buy them with money earned by exporting something else: education services, financial services, tourism services, agricultural commodities, minerals and energy and so on.

This fact of life has been masked by the large mining boom capital inflows that have funded ongoing current account deficits. In other words, we bought flat-screen TVs with other people's capital.

Running through the Council of Australian Governments gathering of state premiers in Canberra yesterday was a pressing question: what will generate future income for Australians to buy things we can’t make competitively?

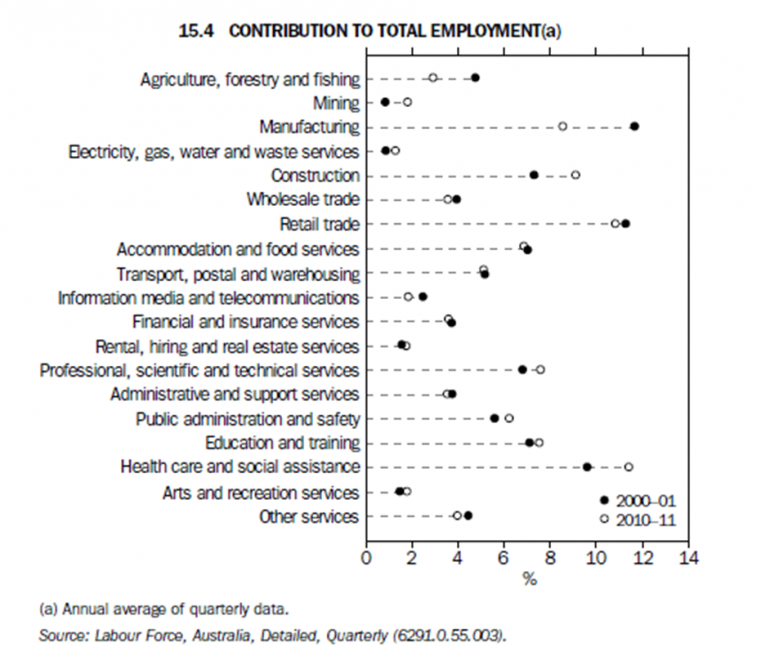

First of all, let’s not write-off manufacturing. It’s a still a huge contributor to jobs in Australia (see the Australian Bureau of Statistics table below). The Coalition will now be looking to ‘advanced manufacturing’ to soak up some of the 30,000 to 50,000 jobs in the parts supply chain disrupted by the Holden closure. Some of those firms may even export parts to Thailand, Japan or elsewhere to put into the cars we buy.

Minerals and energy (especially LNG) volumes have a bright future, but prices are threatened by increasing capacity of competing nations such as Indonesia in coal, Brazil in iron ore and the US in LNG. Moreover, the number of jobs in these sectors is low once the initial construction projects are complete.

Education exports will benefit from the return of the Australian dollar to more sensible levels, a process helped by Reserve Bank governor Glenn Stevens’ comments this week.

However, that is a long-term proposition that relies on continued federal government investment in the tertiary and TAFE systems.

Consulting and financial services get cheaper as the dollar falls. These exports generate a lot of local income, but for a relatively small workforce. The bulk of financial jobs – a large slice of the jobs in this country (see table below) – are part of the domestic economy. Yes, there are plenty of jobs in financing our housing ‘boom’, but they don’t generate foreign reserves with which to buy goods from abroad.

Agricultural commodity prices have a bright future, supported by two mixed blessings: a growing number of mouths to feed in our region and the emergency of an Asian middle class with diets and tastes at least as expensive as our own. The ‘mixed’ part of that blessing is that agricultural resources (and the natural environment) are likely to deteriorate as agricultural profits soar.

The key in agribusiness is to add value to commodities before exporting them. As explained recently, we should not export macadamias if we have the opportunity (and capital required) to export ‘walkabout mix’ (We should be Asia's delicatessen, not its foodbowl, October 25) .

And accommodation services – a key part of our tourism ‘exports’ – should grow too as the lower dollar attracts more visitors.

As the recriminations fly over Holden’s demise, the truth is there are plenty of export areas that can be pumped up – if we can attract the capital to exploit clear opportunities – and discover what it is that the booming Asian middle classes want from us.

Richo made an unusually sound suggestion as to how this might be done. “Let's spend that $200 million [of subsidies Holden was asking for] a year on finding out what that [new export] product is and stop trying to blame someone for a failure way beyond our power to have avoided,” he wrote.

Indeed. It is the role of the private sector to shift capital into the export industries of the future.

However, there is a clear role for government in researching those growth markets, by helping with the kind of R&D the likes of the CSIRO is famous for and promoting ‘brand Australia’ abroad.

The sad demise of Holden is also a reminder to redouble our efforts to figure out what we can sell the world.

If we don’t get that right, say goodbye to your European appliances, zippy foreign cars, and overseas holidays – and just about everything else consumed in our world-beating levels of mass affluence.