Central banks face a bumpy road to policy normalisation

Global interest rates will eventually move higher. We do not know precisely when, how fast, or how far, but we do know the direction. After a long period of very low interest rates following the global financial crisis, some central banks (mainly the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England) are planning to 'normalise' -- that is, to gradually tighten their easy monetary policies as their economies improve. And when US and UK benchmark interest rates go up, interest rates tend to go up elsewhere, too.

Should we worry if and when global financial conditions tighten?

The 2014 IMF Spillover Report prepared by IMF staff looks into what to watch out for and who to watch out for as interest rates begin to normalise. The answer depends on two sets of factors.

First, what is going on in the originating source countries in terms of the underlying drivers behind higher yields -- for example, whether or not stronger growth, say in the US and UK, is the main force behind higher interest rates. Second, what is going on in the receiving countries -- that is, how vulnerable they might be to higher borrowing costs. Both these factors matter for spillovers as highlighted in the report.

Factors that drive yields higher: good and bad spillovers

Higher interest rates and exit from monetary stimulus in major advanced economies when led by stronger growth prospects (real shocks) produce good spillovers. Interest rates tend to rise elsewhere. But they are lifted by a rising tide of economic activity at home and abroad. Another positive development is that trade and capital flows tend to strengthen.

On the other hand, when interest rates move up faster than what is suggested by the real economy (money shocks), things can look quite different. Interest rates elsewhere tend to go up more sharply as liquidity conditions tighten in major financial centers. Capital tends to flow out, especially from vulnerable emerging economies. Foreign activity is dampened. Spillovers then tend to be negative.

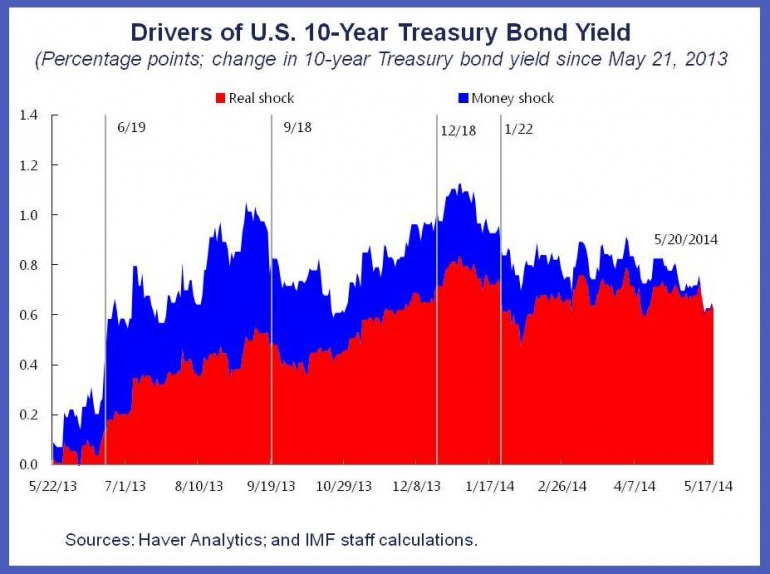

Based on the report’s analysis, the chart below shows what have been the main drivers of higher US long-term yields since the taper episode over a year ago.

Notice what happened last summer. Against a backdrop of low market volatility, low spreads, and high asset prices, mere talk by the US Fed of tapering its purchases came as a monetary shock or surprise to markets (blue area). Around this turning point, interest rates moved higher quickly. Market turbulence ensued. Negative spillovers were felt worldwide. The problem is that the central bank may have had little choice: if it felt market expectations and risk-taking had become too one-sided, some course correction may have been needed.

Whether fully intended or not, Fed communications during the episode have clear lessons going forward. Given an unconventional starting point -- low interest rates and large balance sheets -- major central banks face complex challenges when it comes to normalising smoothly. If markets get well ahead of themselves, financial stability concerns may require higher interest rates even if growth is not stronger. With recent market volatility and spreads falling again to low levels and asset prices moving up (some at all-time highs), this is something to watch out for.

What else matters for spillovers?

On the receiving end, spillovers from higher interest rates depend on local factors too.

During the May 2013 taper episode, for example, spillover effects were not all the same. Instead, effects differentiated across emerging economies depending on their fundamentals and policies. Notably, those with higher external deficits or lower reserves, higher inflation or weaker growth were hardest hit. Their interest rates rose or currencies fell by more.

Moreover, risks can interact. Markets may reassess those economies with weaker fundamentals in the context of rising interest rates and tighter financial conditions. Thus, more vulnerable economies along these lines are the ones to watch out for going ahead.

Bottom line

So should we worry about higher interest rates? Not if stronger growth is the reason. We would happily take it over the alternative of lower interest rates and lower growth.

However, the road ahead is a tricky one. Much will depend on how well the normalisation process can be managed. That is, how smoothly can we transition along a path to higher growth and interest rates? And, given recent market trends, there may be further bumps along that road. Stay tuned.

This piece was originally published at iMFdirect. Reproduced with permission.