Bridging over global economic gaps

At Pimco, we have long believed that the global economic recovery from the financial crisis of 2008 was to be subpar despite the historic amount of stimulus applied in 2009.

The 'new normal' recovery, as we described it then (see Pimco Secular Outlook, A New Normal, May 2009), was fraught with uncertainty. Policymakers in charge of guiding the 'cars' along the global economic 'highway' found themselves collectively standing on one side of a vast chasm that had been widened and deepened by years of rising indebtedness, increasing imbalances, policy incrementalism and growing inequality. This frightening combination of fundamental economic and political challenges best describes the chasm the global policymakers are trying to cross with their 'bridge' of hyperactive monetary and on-again/off-again fiscal policies.

In economic parlance, the world in 2008 was facing a 'deflationary output gap' between vastly diminished aggregate demand (ability to consume) and rising aggregate supply (ability to produce). Years of rapid globalisation, enhanced by technological change, had given the global economy ample ability to produce large and growing amounts of goods and services at lower prices. But the lack of global demand coordination pre-crisis, amplified by a series of policy mistakes resulting in asset and credit bubbles in consumer-heavy developed countries, severely damaged the global economy’s ability to consume these same goods and services post-crisis.

Starting in mid-2009, global policymakers embarked upon an ambitious project to bridge this deflationary output gap with new 'assisted demand' in the form of large fiscal spending, tax cuts and income transfers, all financed by global central banks via near-zero interest rates and quantitative easing. The goal in 2009 was simple: provide a bridge of government-assisted demand to the global economic cars until they collectively found the other side of the chasm.

At first, all the global economic cars responded well. Government-assisted demand provided and financed by public balance sheets and central banks resulted in a classic inventory drawdown, which generated the need for increased production and employment across the global economy.

But soon, the initial demand impulse faded and government bridge-building slowed enough to cause the global economic cars to advance only in fits and starts from there on. Having gone a fair distance already, policymakers from different countries, in charge of different lanes, wanted to keep building the bridge at different speeds and in different directions! Nobody could see all the way to the other side of the chasm, and policymakers from different countries began to disagree substantively on where and how to proceed forward. The initial burst of demand coming from a common and coordinated global plan broke down into a hodgepodge of global policy confusion and inaction.

For the past two years, the global economy has had to overcome all the navigational challenges produced by often-severe bouts of policy confusion. No cars have yet been lost to the chasm, but some cars have simply been halted after their initial spurt by a lack of any bridge-building (Japan). Other cars have had to retrace backward due to very challenging driver-passenger relations that couldn’t tolerate the slow pace and elongated timeframe of the zigzag journey without conflict (the eurozone). And yet other cars have done a much better job of keeping with the straight and narrow original plan of plowing straight ahead toward the other side of the chasm (the United States), but importantly, at the cost of depleting public balance sheets and policy capacity to an even greater extent.

In 2013, all global eyes will be on the United States 'car'. Not only has it progressed the greatest distance across the chasm, but passengers in the US car are reportedly seeing, for the first time, some solid ground under their government-assisted-demand bridge. The US economy offers a glimmer of hope to all those other cars that have suffered this long and uncertain journey post-2008. But, diagnosing the length, breadth and stability of the land under the US bridge will be critical in determining whether other cars follow in the same direction.

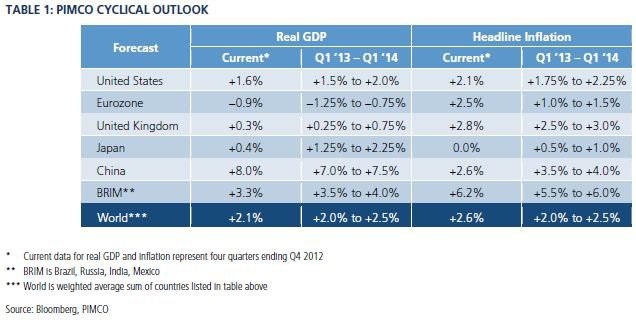

First, the US economy is likely to continue on its New Normal growth path for another year; bridge-building will remain slow despite finding some land. We expect a 1.5 per cent to 2 per cent growth rate for the US economy in 2013. The housing recovery alone will make a substantial positive contribution of between 0.75 per cent and 1 per cent to growth in 2013. But because of substantial depletion of government resources over the past few years, the assisted-bridge-building will slow significantly such that fiscal policy tightening will impart a 1 per cent to 1.25 per cent drag on US growth in early 2013.

What the housing recovery looks like in length and breadth will define the potential and probability both for other global economic cars to follow in the United States’ direction and for the United States car to continue making forward progress to its ultimate destination: the other side of the chasm. We expect a recovery cycle in residential construction that runs through the end of 2014 into early 2015, and which reverts the level of residential investment back to its long-term mean share of GDP. This calls for a 1.5 million annualised housing starts level by early 2015, which we consider 'normal', and cumulative new GDP creation of about 2 per cent from today’s level over the next two years.

This length and breadth of residential investment recovery is expected to be accompanied by a cumulative 5 per cent to 10 per cent increase in home prices over the next two years as well, a further welcome sign of 'normalisation' for household balance sheets that have suffered deep losses in net worth from the peak prices of 2007. Where we differ from consensus, however, is in projecting the effect this rise in home prices will have on consumption growth in the US in addition to investment growth described above.

Traditionally, a $1 increase in home prices is expected to generate between three and eight cents of consumption growth through the wealth effect channel (Fed chairman Ben Bernanke discussed this in a February 2012 speech, Housing Markets in Transition). But this historical observation was made in times when household balance sheets were significantly less leveraged and when banks were much more willing and able to make consumer loans based on rising home values. While the consensus expects a more traditional reaction of consumption growth to home price increases, we expect the wealth effects of rising home prices will be much more muted in the years ahead than history suggests. First, banks are less willing and able to lend against rising home values today. Second, household savings have been significantly depleted during the crisis. And third, an ageing demographic is less likely to take on new debt, all else equal.

Having laid out our expectation for the length and breadth of the US housing recovery, the question returns to whether the other major global economic 'cars' will view this recovery as sufficiently strong to try heading in the direction of the United States. Japan, it seems, has already made a decision to charge toward the US with an aggressive mix of hyperactive monetary policy and new fiscal policy stimulus. We expect Japan to grow by 1.25 per cent to 2.25 per cent in 2013, but we question whether this will be yet another fit-start move or whether Japan will dart forward toward the US over the next few years with continuous assisted-demand growth.

The eurozone, we believe, will remain mired in its driver-passenger conflict. While the US will surely provide confidence to some passengers in the eurozone car, it is highly unlikely in our view that eurozone policymakers will make substantive progress in the direction of the US during 2013. The driver-passenger conflict remains a key concern for eurozone policymakers, and forging an assisted-demand bridge in any direction seems implausible for the time being. We expect the eurozone economy to contract by -0.75 per cent to -1.25 per cent in 2013.

Finally, where do the emerging markets 'cars' fit in all this? Emerging market economies have an important role to play in global bridge-building as well, but with one important difference. Emerging market private and public sector balance sheets are both flexible enough to engage in demand growth. But it is the type of demand growth they provide that is most important for our global outlook. As we have been discussing for the past three years, the emerging market growth model of investment, production and exports is quickly coming to its own natural point of saturation. Primarily because developed market consumption is weak, emerging market investment and production growth is losing value and sustainability as a global demand engine. While we don’t expect any accidents in emerging markets during 2013, we remain concerned that emerging market balance sheets are primarily engaged in investment and production activities as opposed to pivoting to consumption activities. We expect China to grow between 7 per cent and 7.5 per cent in 2013, and we expect the other major emerging market economies to grow between 3.5 per cent and 4 per cent this year.