A rate cut is still on the cards

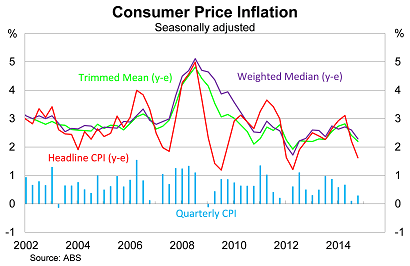

Annual inflation continued to ease in the December quarter, placing pressure on the Reserve Bank of Australia to cut interest rates. But the headline figure is fairly rubbery-- readers should pay more attention to the core measures, which will also be the focus of the RBA when it makes its decision in February.

On a seasonally-adjusted basis, consumer prices rose by 0.3 per cent in the December quarter, weaker than expectations, to be 1.6 per cent higher over the year. Annual inflation has effectively halved within the space of six months and is poised to drop lower by the end of the financial year.

Core measures of inflation -- which remove volatile items -- were somewhat stronger and actually exceeded expectations. The trimmed mean measure of inflation rose by 0.7 per cent in the December quarter, to be 2.2 per cent higher over the year. The weighted median measure also increased by 0.7 per cent in the quarter and is now 2.3 per cent higher than this time last year.

The main contributors to inflation in the December quarter were domestic holiday travel and accommodation (up 5.8 per cent in the quarter), tobacco (up 4.8 per cent) and dwelling purchases by owner-occupiers (up 1.1 per cent). Offsetting these factors were automotive fuel (down 6.8 per cent), while audio, visual and computing equipment and services fell significantly.

With headline inflation now below the RBA's medium-term target for annual inflation of 2 to 3 per cent, attention will naturally turn to when the bank will cut rates. However, readers should be aware than any decision to lower rates will be made based on expectations of future inflation rather than what has happened over the past six months.

There are two good reasons why the bank won't pay too much attention to headline inflation right now.

First, annual inflation is artificially low due to the removal of the carbon tax. Based on data released in September, most businesses passed on the savings from the repeal in full (Inflation will stay the RBA's hand, for now, October 22). Essentially this has shifted down the rate of inflation until the September quarter this year.

Second, to some extent the recent weakness reflects temporary and volatile factors. As with other countries, Australia is experiencing an oil price shock that will continue to weigh on inflation over the next six to 12 months. But the shock is likely to be temporary: either low oil prices will prove persistent or prices will begin to turn around. Both scenarios will result in stronger domestic inflation.

So does that mean the RBA should leave rates as they are? Not exactly.

The Australian economy remains exceptionally weak and has failed to rebalance as quickly as the RBA had hoped (Will the RBA make the right rates call?, January 26). That by itself provides justification for cutting rates, since a soft outlook for growth will inevitably weigh on inflation down the track.

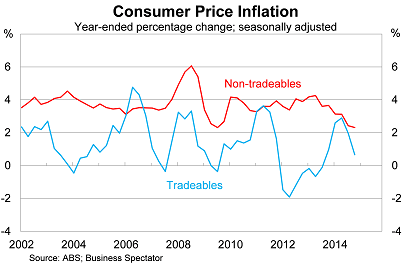

We are already beginning to see the effects of weak growth on inflation and inflation expectations. Consider, for example, the following graph, which shows inflation on tradeable and non-tradeable goods.

Historically the RBA has relied on cheap imports to maintain their medium-term target. From 2000 until 2013, prices on non-tradeable goods rose by 3.75 per cent each year, largely reflecting domestic price pressures.

But look what has happened more recently: price growth has eased to its slowest pace since September 2009. Obviously some of this reflects the repeal of the carbon tax, as mentioned earlier, but the driving force has been a weak labour market and historically weak wage and productivity growth.

This downward shift won't get as much attention as oil prices will and it certainly won't feature in most media reports but it is absolutely the more important narrative for domestic inflation. Wage growth is set to trend lower in the near-term, owing to a mixture of high unemployment and a mismatch in skills between the jobs being created (non-mining sector, mostly services) versus those being lost (mining sector and manufacturing).

There is a very real risk that, unless the RBA takes immediate action, lower inflation expectations will become entrenched within wage negotiations. Once that happens, it will become more difficult for the RBA to maintain its existing inflation target.

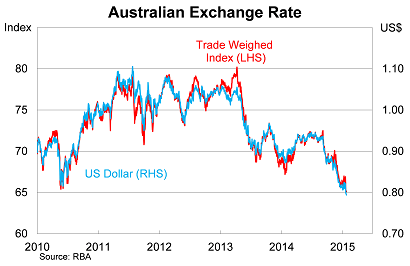

The outlook for inflation on tradeable goods is naturally more difficult to determine. About 30 per cent of the price of tradeable goods is captured through the exchange rate (compared with just 10 per cent for non-tradeable goods).

The Australian dollar has declined by around 9.5 per cent against Australia's trade-weighted index since the end of June. The effects of this have yet to be fully passed through, but based on some simple calculations, a softer dollar could contribute between 0.8 percentage points and 1.0 percentage point to annual inflation over the next year.

Readers shouldn't dwell too much on the headline figures in today's inflation report. The combination of the carbon tax plus oil prices makes the headline figure fairly unreliable.

The RBA will instead concern itself with core measures of inflation -- the trimmed mean and weighted median measures -- and the outlook for inflation beyond the next six to 12 months. Those figures, combined with the knowledge that the economy isn't rebalancing as quickly as initially hoped, can easily justify a further rate cut should the bank decide to move in February.