Will the markets melt up?

Summary: Record low interest rates and “melted up” bond prices justify higher share prices despite the gloom about the world economy. A “melt up” is entirely possible, especially in high-yield share prices, which could defy fundamentals for some time. Later, increased prices could drive lower future returns or even suffer a meltdown. |

Key take-out: Instead of following the herd investing in high-yield stocks, perhaps value style and emerging market shares deserve a look. Be especially careful buying fixed-rate bonds. Property is more fairly priced after yesterday's rate cut, but not if wages fall. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors, speculators, bond investors. Category: Shares. |

Experts have suggested this year will be a volatile one, which could be a way of saying they don't have a clue what's going to happen. Based on the accuracy of past predictions, this may be a more honest approach to forecasting. However there does seem to be uniform pessimism about world growth, with the US being the only engine keeping Nouriel Roubini's so-called single-engine global economy flying. It may seem counterintuitive but this may actually drive a “melt up” in share prices this year, complementing the already melted up bond market. Let me explain.

What's a melt up?

Since bad news sells more than good news, the phrase “melt up” doesn't appear as often in the media as the more worn “melt down”. A melt up is simply the opposite. It is when investment prices rise rapidly and well above fundamentals. According to Investopedia, a melt up is driven by a stampede of investors who don't want to miss out on rising prices. Perhaps today we should say instead it is being driven by a stampede of central bankers, or simply yield-hungry investors.

It should be no surprise that melt ups often precede melt downs, so be warned.

Melted bonds

World bond prices have reached ridiculously high prices, bought by central bankers with electronically printed money and speculators practising the mantra “Don't fight the Fed”. Buying bonds at current ultra-low yields can only be fundamentally justified if we are turning Japanese and entering a similar prolonged period of deflation and zero interest rates. At the moment investing in the highest credit quality bonds means earning…

- 2.25% per year for 10 years lending to the Australian Commonwealth Government

- 1.8% lending similarly to the US Government

- 0.3% to the German or Japanese Governments

- And having to pay the Swiss Government 0.1% each year for them to hold your money that long.

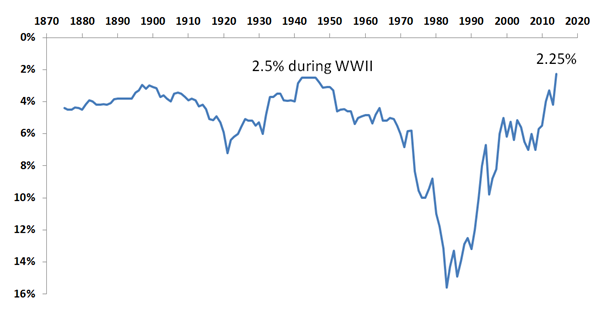

Figure 1 shows the yield from 10 year duration Australian Commonwealth bonds since 1870, highlighting that prices have never been this expensive (yields so low).

Figure 1: “Price” (yield shown inverted) of 10 year Australian Commonwealth bonds since 1870

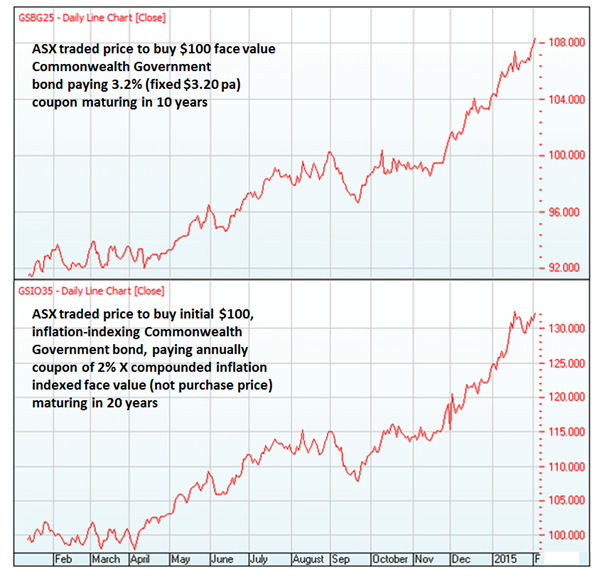

Last year the Australian Government started selling bonds on the ASX which gives us another way to see prices melting up.

Shown below in Figure 2 are bond prices for a 10 year nominal (GSBG25 paying a 3.25% coupon times its $100 face value) and 20 year inflation-linked (GSIO35 paying 2% times its inflation indexing original $100 value) bond. These charts show you have to pay $17 and $31 more to buy these modest income streams than you did just twelve months ago (or about 20% and 30% more). By the way, paying $109 to buy a bond paying $3.25 in annual interest and $100 at maturity in 10 years, works out at the 2.3% annual yield noted earlier.

Figure 2: Prices to buy a 10 year nominal (top) and 20 year inflation linked (bottom) Australian government bond on the ASX over the last 12 months to February 3, 2015

In September (see A dozen ideas for this odd market, September 24, 2014) I suggested readers would get better value buying shorter duration term deposits than locking in for five years to a 3.2% return investing in a benchmark mix of Australian Government and Corporate fixed rate bonds. So far that's looking like a premature call as those bonds have appreciated more than 4% since – though inflation-linked bonds I suggested as an alternative rallied 6%. Anyway, fancy now locking in for 2.5% for five years?

This shows the problem with investing during a melt up. Prices keep rising until they peak.

An equity melt up?

The primary reason to believe there could be continuing equity price rises is because the alternative of setting aside money in bonds and cash has become even more unrewarding.

Take popular dividend paying stocks Commonwealth Bank and Telstra. At current prices of $90 and $6.70 their dividends yield 4.8% and 4.5% (and 6.9% and 6.5% for nil tax rate pension investors counting tax refund). To match a hard to find deposit rate of 3.5%, share prices would need to rise to $120 and $8.35 (and $175 and $12 for pension investors, though don't expect that).

Earlier I shared with readers 50 years of the price-earnings ratio of the All Ordinaries (see A pointer to higher returns, August 29, 2012). There I pointed out that P/Es of less than 10 for the market were entirely normal while interest rates were about 15% in the 1970s and early 80s. Now with interest rates oppositely positioned around 2.25%, it would be normal to expect shares trading above 20 times earnings.

The second reason to expect further rises in share prices is because of the continuing stimulatory effects of low interest rates and now low energy costs. Recall OPEC quadrupled oil prices in 1973 which drove the world into a deep recession. With oil prices halved shouldn't we be celebrating a bit more? Inflation is low and technology is advancing, stimulating new demand and opening new markets. The lower Australian dollar will also make our exporters more profitable (in local dollar terms) and imported tourists more welcome.

What goes up, goes …

While we can't answer how much further share prices can go up, we can say confidently they are starting from an already high starting point.

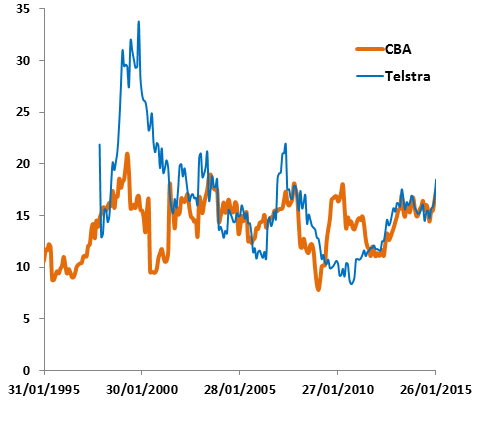

Figure 3 shows the price of CBA and Telstra divided by their last year's earnings (so called trailing P/E ratio) for the last two decades. The current P/E of CBA of about 17.5 has only been this high briefly four times in the past – in early 2010, November 2007, in 2003 and 1999. Sadly those times were followed by a correction.

Telstra investors perhaps can take more heart that investors in the past have paid more than today's 18.5 times earnings more times in the past, however that is including dot-com melted up valuations in the late 1990s which preceded a multiyear decline in fundamental pricing of 3x.

Figure 3: Price earnings ratio (trailing P/E) of popular high-yield stocks CBA and Telstra

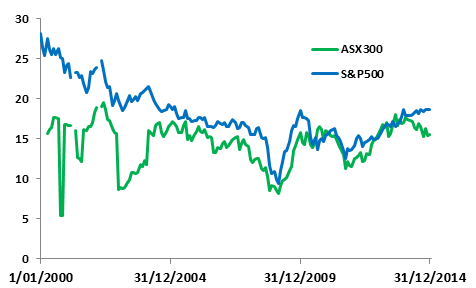

Figure 4 shows that the current P/E of our local market (the ASX300) at 16 and the US S&P500 at 18 is pricey but not unprecedented. Our recent drop flows from the drop in commodity prices (including BHP's P/E falling to 9 from 21 only two years ago).

Figure 4: Trailing P/E of the All Ordinaries and S&P500 to 31/12/2014

At 2.25% yield the P/E of a 10 year Government bond is a whopping 44 times which is very pricey for a no-growth security (oh and a P/E of 300 for German and Japanese bonds). I guess this makes paying 33 times for a net residential property yield of 3% seem not so bad. REITs finished 2014 trading at a not unreasonable 10% premium to their underlying asset values, up from a discount of 3% at the start of 2014 (and a 35% discount five years ago). Up from here their prices start to smoke.

While today's share valuations look almost as alarming, perhaps they shouldn't be looked at in the context of an “old normal” where bonds provided yields of 5 to 7% – more than double what they do now. At yields of 2.4% or below, bonds issued by highly indebted sovereigns who can't balance their budgets don't seem so safe an alternative to shares to me – a bond myth perhaps?

So maybe we need to get used to higher share market prices and shouldn't be surprised if share prices, especially those of high-yield bond substitutes including property trusts and infrastructure, melt up (further).

Indeed what goes up might also stay up, at least while bond yields and interest rates stay down.

Figure 5: Last 12 months to 3 February 2015 price rises in CBA, Telstra and REITs melting up?

Take care

On reflection the above sounds like “this time is different” logic which Professors Reinhart and Rogoff prove expensively wrong studying eight centuries of financial folly.

While market timers might bet on a melt up, others should question investing new money in shares in case future price gains get given away … one day. X-factor corrections don't go away just because bond yields are so unattractive – though maybe they just don't last as long? Or go so deep? Instead of following the herd investing in high-yield stocks, perhaps value style and emerging market shares, which have had a poor run of late, deserve a look.

Be especially careful buying fixed-rate bonds as you may regret locking in for so little or future losses selling before maturity. Inflation-linked bonds defend against surprise inflation and cash won't suffer from capital losses when bond yields revert (note I didn't say “if” and I'll be right one day).

Property became more fairly priced after yesterday's (February 3, 2015) rate cut but not if wages fall or people struggle to just earn them.

Dr Douglas Turek is principal advisor with family wealth advisory firm Professional Wealth (www.professionalwealth.com.au)