Housing is Australia's great boondoggle

If Joe Hockey’s audit committee is looking for a way to save a lazy $43 billion a year, the middle and upper-class welfare that is Australia’s housing policy might be a good place to start.

The Grattan Institute’s Renovating Housing Policy has determined that this massive wealth transfer puts $36 billion in the hands of existing homeowners and a further $6.8 billion goes toward subsidising owner-investors into a product that delivers yields that are generally lower than equities or fixed interest. Between them, owner-occupiers and investors receive over 90 per cent of government funding directed towards the housing market.

For homeowners this includes the exemption of capital gains worth $14 billion a year and the non-taxation of housing services to the tune of $9.6 billion per year. Investors benefit from negative gearing and discounts on the capital gains tax. First home buyers receive the first home buyers grant, which while popular, largely accrues to home owners via higher prices.

Amazingly Grattan’s research suggests that home ownership levels would be broadly the same without the government’s policies, indicating that many housing policies merely exist as a wealth distribution vehicle. The report confirms that government tax and welfare policies are contributing to housing unaffordability in Australia, with most of the welfare pie directed towards home owners and high income earners.

It’s achieving the opposite of what good government policy is supposed to do – assisting those who would have bought property regardless, while driving up prices for those least able – first home buyers and renters.

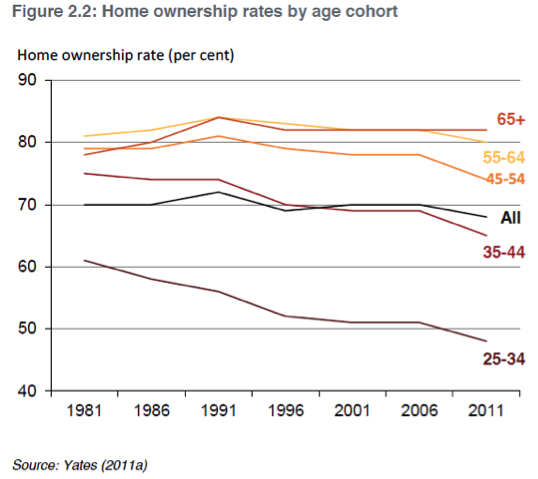

In the mid-1980s, the dwelling-price-to-income ratio was around 2.5 but that has increased to around 4.5 in 2013. This largely reflects sustained economic growth and structural changes such as the movement towards multi-income households and higher risk preferences. Consequently, housing has become increasingly less affordable for those looking to enter the market, reflected by the decline in home ownership rates among each age group under 55 over the past thirty years.

This wealth distribution process will begin to unwind at some point, particularly with the ‘Baby Boomer’ generation beginning to retire in 2011. As this generation exits the workforce their influence on the housing market (and a range of other economic outcomes) will change, and prices will begin to reflect the earnings, wealth and risk preferences of the younger cohorts seeking to enter the market.

Both government policy and demographic change represent long-run influences on house prices, which exist outside the short-run dynamics that market analysts traditionally focus on. Demographic change will take place over decades, while change in government policy may not occur at all. These changes should not be mistaken for the broader discussion on whether Australia has a house price bubble.

More broadly, the effect of demographic change is a debate that we need to have, with housing comprising a small part of a much broader discussion. A debate which will one day be at the centre of political discourse and include a range of policy challenges for governments at all levels. The transition of the ‘Baby Boomers’ into retirement will affect everything from the housing market and the labour force to health care expenditures and taxes.

The reality is that labour market participation has already peaked and will decline over the next two decades. The rise in participation of older people and women has hidden the effects of an aging population for some time but that has begun to change.

Higher levels of immigration would mitigate the problem somewhat, but which political party will face up to such an unpalatable proposition in the eyes of voters? It might require a level of political leadership beyond the current crop.

The discussion is only beginning and the policy responses to this demographic shift are uncertain. However, I will offer one policy promise: the government will not be wasting $43 billion on homeowners and investors ten years from now. If Treasurer Joe Hockey is looking to reduce waste the sacred cow of inefficient housing subsidy should be done away with.

Callam Pickering is a former Reserve Bank of Australia economist.