Europe takes a battering for Brussels' stability and growth delusions

The European Stability and Growth Pact is based on the principle that stability and growth are enhanced when government deficits are either minimised or eliminated. I want you to dispassionately consider an argument that reaches a different conclusion. It may sound like something you have heard before from others and already dismissed. But bear with me.

When considered from a strictly monetary point of view, an economy can be regarded as having five major sectors: households, firms, the government, the banks, and the external sector. To focus on money flows, I will diverge from mainstream economic theory by treating households as consisting exclusively of workers, while I will combine firms and their owners into the firm sector, and do likewise with banks and their owners. I also treat the central bank as part of the government sector, and I ignore capital and income flows between nations in this simple exposition.

Neither households nor firms can produce money, while the other three sectors are potential sources of money. As is now well known (though this fact is still contested by academic economists), banks create money by making loans:

Whenever a bank makes a loan, it simultaneously creates a matching deposit in the borrower’s bank account, thereby creating new money. (Bank of England Quarterly Report 2014 Q1, Money creation in the modern economy.)

Governments can also create money by running a deficit (if it is financed by the central bank, or by bonds sold to banks in return for excess reserves). Money can also be created by running a balance of payments surplus (which in this simple exposition is exclusively a balance of trade surplus).

In order to simplify my argument, I will assume that

- Government spending goes exclusively to firms;

- Taxes are paid exclusively by firms;

- Only firms borrow money from banks;

- Banks charge interest on loans but do not pay interest on deposits;

- Only firms trade with the external sector, selling goods as exports and buying goods as imports;

- Initially, the external sector is in balance so that exports equal imports; and

- Initially, the government sector is in balance so that government spending equals taxation

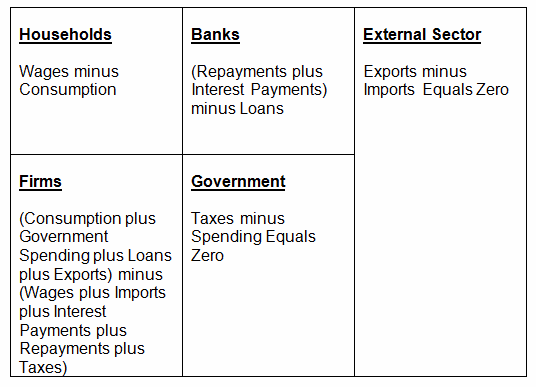

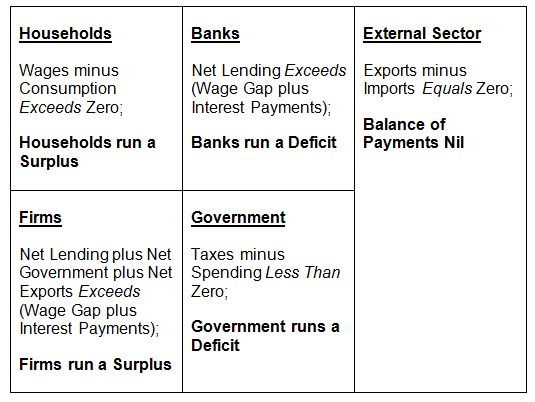

These assumptions lead to the pattern of monetary flows shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Basic monetary flows

Next I assume a growing economy, and add the long-term viability conditions that both households and firms must have an excess of receipts over expenditure over time: they must run a surplus. The viability conditions if the economy is to grow are therefore that:

- Wages exceed consumption; and

- The revenues of the firm sector exceeds its expenditure

When these are added to the initial assumptions (which I will relax later) that exports equal imports and government spending equals taxation, we get the situation shown in Table 2:

Table 2: Viability conditions and balance assumptions imposed on Table 1

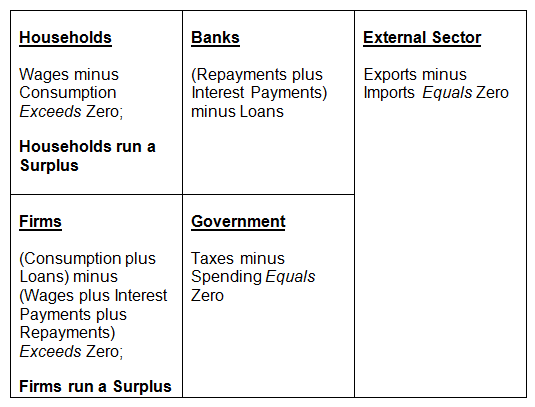

We can refine this further by noting that the condition that households run a surplus means that the inflow to the firm sector from consumption is less than its outflow to households as wages. Call this difference the ‘wage gap’. We can now state a condition that is necessary for the firm sector to run a surplus:

- Loans must exceed the sum of interest payments, repayments and the wage gap

This means that for the firm sector to be viable, the banks must run a deficit: new loans by the banking sector must exceed the sum of interest payments and repayments by more than the difference between wages and consumption. Therefore, for the economy to grow, loans must exceed repayments by more than the sum of the wage gap plus interest payments (with the gap enabling the firm sector to run a net profit).

This aggregate viability condition is shown in Table 3: Loans minus repayments must exceed the wage gap plus interest payments if the firm sector is to run a surplus.

Table 3: with viability conditions imposed

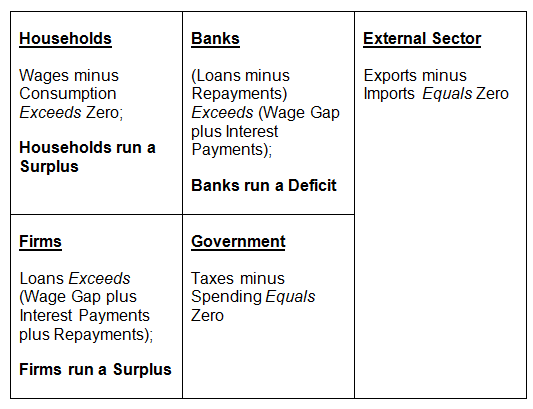

Now the question arises: what if banks don’t do that? What if net bank lending (loans minus repayments) is below this viability threshold? Then the capacity of the firm sector to makes a profit evaporates, and the economy goes into a slump -- and the result generalises to the more general situation in which the household sector also borrows to finance consumption or speculation.

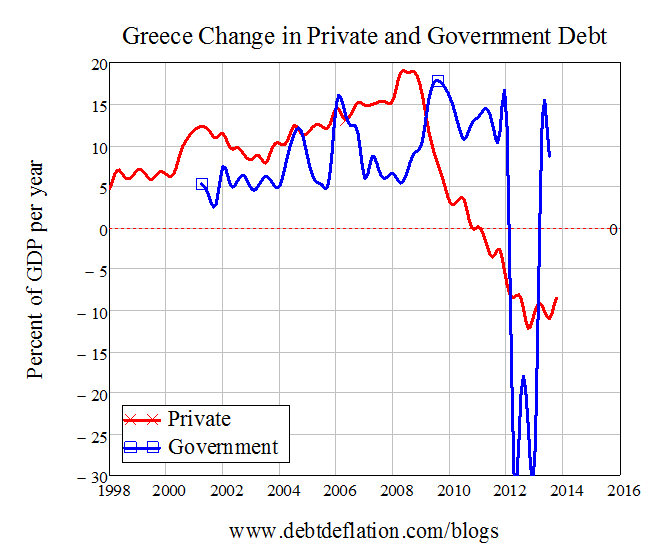

This is not a hypothetical situation, since this is precisely what caused the global economic crisis. It was the most severe downturn since the Great Depression because net bank lending fell not only below this threshold, but below zero in many countries -- in the US between late 2009 and 2011 (Figure 1), and in Greece since 2011 (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Private debt change and US Unemployment since 1990: correlation-0.9

Figure 2: Private debt change and Greek Unemployment since 1990: correlation-0.94

In many countries therefore, the desirable situation shown in Table 3 gave way to the undesirable situation shown in Table 4 (where I have replaced ‘lending minus repayments’ with ‘net lending’). Here the firm sector is running a deficit while the banking sector is running a surplus -- and economic activity is contracting as a result.

Table 4: An economy in crisis with non-viable private banking sector behaviour

How should government policy respond to this? There are two options: either it runs a deficit (so that taxes minus spending is negative), or a surplus. The potential impact of a government deficit is shown in Table 5 -- with the government running a large enough deficit, then the firm sector can return to a surplus even if net lending is still negative.

Table 5: Government running a deficit in response to negative net lending

The alternative case -- the government running a surplus in response to net lending turning negative -- is shown in Table 6. Since we started from a situation in which the firm sector was already running a deficit, the government surplus forces them to run a larger deficit still.

Table 6: Government running a surplus in response to negative net lending

These two policy alternatives can have a drastic impact on the behavior of the firm sector. With the firm sector returned to a surplus by a large enough government deficit, it is possible that net lending can turn positive again -- since firms would be less worried about going bankrupt and could reduce the level of repayments (and also be willing to borrow again). But a government surplus maintains the pressure on the firm sector to continue reducing its debt levels.

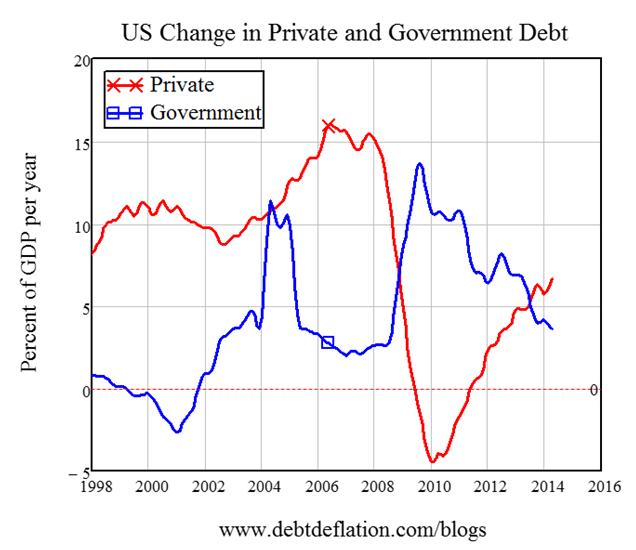

Again, this is not a hypothetical situation: it neatly characterises the difference between what has happened in the US (where the government deficit rose and stayed elevated during the crisis) versus Europe (where the emphasis has been upon public austerity to reduce government debt). The US government deficit rose during the crisis, and stayed high until the private sector began to borrow money again (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: US government deficit rises until private sector deleveraging stops

In contrast, the Greek private sector has continued to delever -- because the austerity imposed by the Growth and Stability Pact is forcing it to do so (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Greek private sector deleveraging continues under the policy of austerity

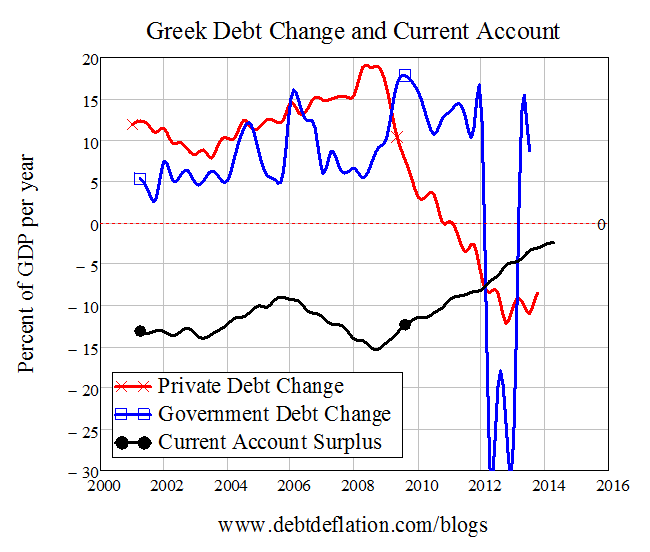

In the stylised but realistic model outlined here, the only way that the government surplus approach of Table 6 can be compatible with the private sector returning to surplus is if the current account surplus compensates for the surpluses being run by both the banking sector and the government -- as in Table 7.

Table 7: The only way for bank and government surpluses to be compatible with a firm sector surplus

However there are two obvious problems with this -- one a general problem, and the other specific to the EU. Firstly, the external sector is necessarily a zero-sum game at the global level -- the sum of all external balances must be zero (unlike the situation for both the banking sector and the government, where global private and public debt levels can either rise or fall). Secondly, a major method by which a country can generate a balance of payments surplus is via the medium term impact of a devaluation. But the countries of the eurozone can’t devalue. So while the Greek current account has improved, it still hasn’t been enough to counter the impact of sustained private sector deleveraging (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: An improving Greek current account hasn't compensated for private sector deleveraging

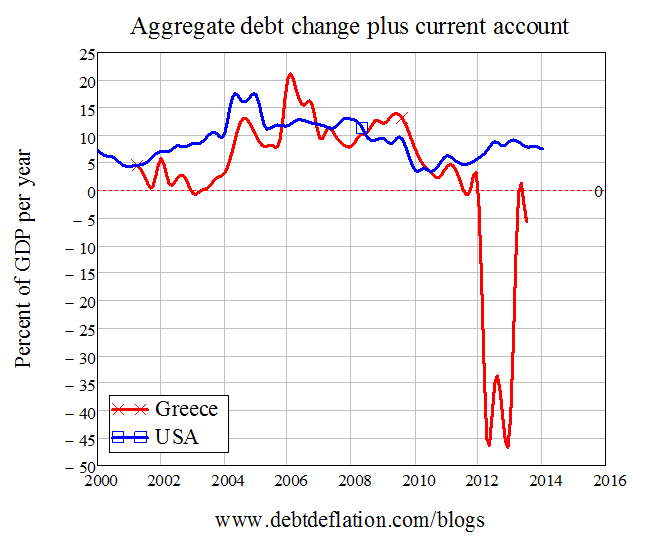

Greece’s plight under the EU’s austerity policies contrast strongly with America’s current situation. The attempt by Brussels to achieve the situation shown in Table 7 -- where all sectors run surpluses -- has failed. The sum of private and public debt change plus the current account surplus has been strongly negative in Greece since 2012, and well below the ‘wage gap plus interest payments’ threshold identified in the simple model outlined here. Greece has been plunged into a Great Depression as a result.

America, in contrast, has maintained an aggregate deficit by the three money-generating sectors -- the banks, the government, and the external sector -- which has enabled the two money-using sectors to maintain surpluses (see Figure 6). Though insufficient to prevent a serious downturn, they have stopped that downturn becoming a Great Depression.

Figure 6: An aggregate expansionary situation for the US versus serious contraction for Greece

There is no doubt that the current global economic situation is far from ideal: The economy should never have been allowed to fall into the private debt trap that caused this crisis in the first place. But given that it did so fall, the sensible policy to aim for is that shown in Table 5: the government should run a deficit to counter the surplus being run by the banking sector. The policies being followed by the EU, which are better characterised by Table 7, are unsustainable and have turned a serious crisis into a Great Depression. They should be abandoned in place of government deficits to counter and eventually reverse private sector deleveraging.

In the long run, the policy objective should be to achieve the situation shown in Table 8: Both the banking sector and the government should run deficits, households and firms should run surpluses, and the external sector should be in balance.

Table 8: The desirable suite of deficits and surpluses

That ideal is a long way off for virtually every country on the planet. But the EU should make the first move, and implement deficit spending by its governments so that southern Europe can end its private-sector deleveraging, and climb out of its policy-imposed Great Depression.