Bonds for the better

Summary: The Australian impact investing market is still fragmented and immature. The market faces several challenges including illiquid and unproven products, an absence of large scale opportunities, the difficulty of measuring social outcomes and super funds' legal obligations to beneficiaries. Both governments and philanthropically minded investors can help address these issues. |

Key take-out: The capital flows into impact investing are potentially huge, but it could take another decade or two for demand for capital to fully respond to increased supply. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Economics and Investment Strategy. |

‘Impact investing' refers to investment with the intention to achieve both a positive social, cultural or environmental benefit and some measure of financial return. In their 2011 publication, Antony Bugg-Levine and Jed Emerson described it as ‘disrupting a world organised around the competing principle that for-profit investments should seek only to pursue financial return, while people who care about social problems should give away their money or wait for government to step in'.

But just how big a ‘disruption' are we likely to see?

If the estimates of some leading analysts are to be believed, then the answer is: a very big one. A 2009 Monitor Institute report concluded that a global impact investing market of $US500 billion – representing 1% of assets under management in 2008 – could be achieved as early as 2014. This could include capital placed in businesses, non-profits or funds in a range of forms, such as equity, debt, working capital lines of credit, and loan guarantees.

In the Australian context, where $2,000 billion sits in funds under management, adoption of the Monitor Institute's key assumption would lead to a projected impact investing market worth $20 billion. But the year is now 2014 and the Australian impact investing market remains fragmented and immature.

Commentators routinely cite the same landmark deals as precedent for further activity; the debt-funded acquisition of ABC Group by the SVA-led Goodstart Early Learning consortium; the NSW Government's two ‘pay for success' contracts, commonly known as social benefit bonds (SBBs); and the various debt, equity or quasi-equity investments of the three Social Enterprise Development and Investment Funds (SEDIFs), seeded by the Australian Government.

Working closely with SVA Impact Investing, which raised funds for the first SBB and the Social Impact Fund, SVA Consulting interviewed 20 industry leaders to better understand why the Australian impact investing market is yet to reach the scale that some have predicted.

In this article we explore the challenges, on both the supply and demand side, which investors, investees, intermediaries and government must negotiate to ensure that the market does flourish. We take a look at the international experience, pointing to a range of initiatives that Australian governments could consider in providing catalytic support to encourage the market's development.

Challenges to the growth of impact investing

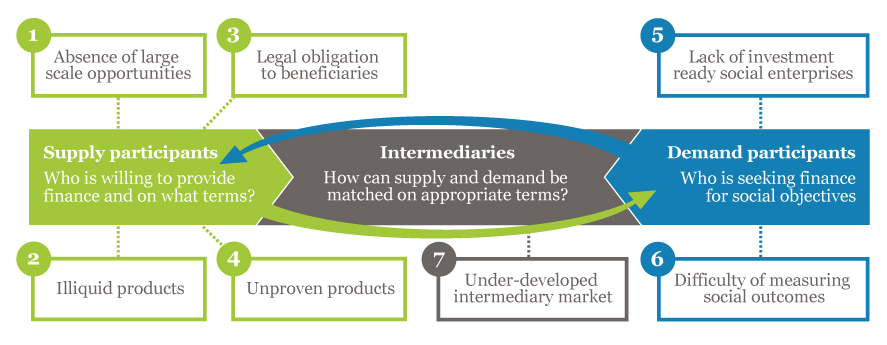

At present, deficiencies exist on both the supply and demand sides of the market. Sustained growth is constrained by the market's capacity to match the two on appropriate terms.

We identified seven challenges to the growth of the impact investing market, each of which is explored in further detail and plotted with reference to the dynamics of the market in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Seven challenges to the impact investing market

1. Absence of large scale opportunities

With the Australian impact investing market still in its infancy, the majority of deals have typically been small and relatively resource intensive. Early deals have therefore been contingent on the involvement of investors keen to build a track record for this form of investment. To achieve this, these early movers have been willing to invest time and resources above and beyond what might otherwise be considered cost effective. Typically, these have included high net worth individuals, foundations or private ancillary funds, to whom or to which scale is less important.

STREAT's 2012 acquisition of the Social Roasting Company's two cafés and roasting business is a celebrated Australian social finance case study due to its innovative use of equity to fund social enterprise expansion. Yet the deal involved four separate investors, a host of pro bono legal and financial advisers and was worth only $300,000.

2. Illiquid products

Investor concerns over illiquidity arise due to the absence of an established secondary market. This issue is compounded in the context of a fund. It's an issue for fund managers who may wish to rebalance their investments and it's an issue for investors who may wish to sell their units. As CEO of the Responsible Investment Association Australasia, Simon O'Connor, explains, “It's not that impact investing assets can't be on-sold, it's just that we haven't yet seen how it would work.”

Internationally, organisations are pursuing innovative methods of addressing illiquidity in impact investing. In the UK, investment manager, Threadneedle, has partnered with The Big Issue's investment arm to offer a cash equivalent ‘bond fund' designed to appeal to both retail and institutional investors and offering investors the opportunity to cash out quickly. The fund will invest in fixed income securities of organisations – companies, associations, charities and trusts – which support socially beneficial activities and economic development. Threadneedle CEO, Campbell Fleming, explains that they ‘have worked with Big Issue Invest to develop a concept that allows people to direct a portion of their savings into investments with a social benefit, through a transparent and liquid vehicle which also aims to generate a return in line with a UK corporate bond index.'

Such initiatives though are in their infancy and until the impact investing market achieves some level of maturity, illiquidity will remain a factor in the risk/return calculations of any potential impact investor.

3. Legal obligation to beneficiaries

Superannuation funds have pointed to legal obligations owed to their beneficiaries as an obstacle in backing investments with blended social and financial returns. The Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth) enunciates the ‘sole purpose test' requiring trustees to manage funds solely for the benefit of fund members.

There are two prevailing responses to these concerns. The first is that, with care, the requirements imposed on trustees can be navigated by integrating the objectives of impact investment into a comprehensive investment strategy that has proper regard to considerations of ‘risk, return, cash flow, diversification, liquidity, valuation data, tax, costs and the liabilities of the fund'.

Michael Traill, SVA CEO

The second response is that competitive market returns are, in fact, compatible with social returns. SVA CEO, Michael Traill, is quick to point to the 12% returns enjoyed by investors in Goodstart Early Learning – Australia's largest impact investing deal to date – which have more than doubled the average return of superannuation funds over the same period.

A third response would, of course, be for government to legislate to provide greater comfort to fund managers as to the extent of their obligations.

4. Unproven products

Mainstream investors are typically conservative and are reluctant to invest in products that do not boast an established track record. One ethical funds management group, responsible for the investment of $700m, said that it would be unlikely to consider a product that didn't have at least a three year track record.

There is substantial overlap between each supply side challenge and the Australian impact investing market's limited track record. As deal flow and innovation increases and investor comfort grows, such challenges will be overcome.

Underpinning these supply challenges is, of course, the need to offer products with appropriate risk/return profiles to attract target investors. The true risk/return profile of impact investing products will only become clear over time. SBBs are a case in point. Newpin, Australia's first SBB, was launched in July 2013 and while initial results are encouraging, the bond is due to run for seven years. Late last month the bond offered its first annual yield payment to investors of 7.5%. Though there is not pre-defined yield on the bond it certainly marked a healthy start for this prototype bond in the Australian market.

Les Fallick, Founder and Director of Principle Advisory Services and a Director of the Fred Hollows Foundation, has identified increasing appetite for impact investing opportunities amongst institutional pension funds, particularly non-profit industry funds. “If intermediaries and investees can raise awareness and engage pension funds with a working model that offers diversification, uncorrelated risk and appropriate returns, then institutional support for impact investing is inevitable.”

5. Lack of investment ready social enterprises

Ian Learmonth, SVA's Executive Director of Impact Investing

Despite the importance of, and difficulties associated with, engaging institutional investors in order to achieve scale, SVA Impact Investing is unequivocal that the immediate challenge lies on the demand side of the equation. “It's not an absence of investors that keeps us up at night,” says Ian Learmonth, SVA's Executive Director of Impact Investing. “Finding opportunities that are capable of generating suitable financial returns, but also meet SVA's high standards in relation to social impact, is the challenge.”

Ben Gales, CEO of Social Enterprise Finance Australia

Whether as a direct result of such avenues of support, or otherwise, demand for social enterprise investment may gradually be responding to supply. The CEO of Social Enterprise Finance Australia (SEFA), Ben Gales, points to strong growth in SEFA's pipeline over the last six months, which now has over $15 million worth of opportunities. Whilst acknowledging that it may have taken SEFA some time to find its feet, Gales maintains that the quality of organisations approaching SEFA for finance has improved significantly. “It has just not been a matter of SEFA looking harder and smarter,” Gales explains, “they've found us!”

6. Difficulty of measuring social outcomes

The core feature of an impact investment is the pursuit of both financial and social returns. As such, the risk/return profile is inherently more complex than that of a traditional investment, which exclusively seeks financial returns. Philanthropic-minded – or ‘social-first' – investors may be familiar with valuing social outcomes. Mainstream, ‘finance-first' institutional investors are not.

With impact investing in its infancy, investor attitudes towards social returns vary dramatically. One Singapore-based intermediary explained that “there is a lot of academic interest in impact reporting – and rightly so – but we often find that high net worth individuals (for example) are only interested in knowing that their investment has created a handful of jobs for disadvantaged people.”

This may be so, but as the market develops, expectations around the rigour of measurement, evaluation and reporting of social impact will increase.

7. Under-developed intermediary market

The established relationships of a credible intermediary are crucial in attracting and securing investment. Traill attributes SVA's success in filling – and even over-subscribing – the Newpin SBB and Social Impact Fund to SVA's deep and long-standing relationships with investors.

But the level of familiarity amongst those investors with emerging social finance products is also important. Commercial banks enjoy deep and long-standing relationships with investors, but those investors are more familiar with mainstream fixed income products. It is not surprising, then, that commercial banks might find it difficult to effectively market impact investing products to their traditional client base, as was the case with the recent Benevolent Society SBB. Intermediaries must be capable of connecting those who are familiar with and interested in investing for social impact with social sector organisations that need capital to achieve positive social change.

Overcoming these challenges

While government has a critical role to play in developing an enabling environment, investors, investees, and intermediaries can also help to overcome challenges to the growth of the Australian impact investing market.

Government

Governments in Australia have, of course, made a start on supporting the impact investing market. In addition to the $20 million of Federal Government seed funding, which established the three SEDIFs, the Western Australian Government established the $10 million Social Enterprise Fund in 2012. This fund aims to increase the number, effectiveness and efficiency of social enterprises in WA. In creating Australia's first two SBBs, the NSW Government has sparked a high degree of interest amongst other state governments, particularly Queensland and South Australia, with the latter having released a discussion paper in December 2013 to explore the SBB opportunity.

But such initiatives must be sustained and must send a clear message of support for the development of a more efficient and effective, for-social-purpose capital market.

On the supply side, the Australian Government could address the legal and regulatory barriers to impact investing by legitimising the consideration of social returns amongst Australian corporations, charity trustees and fund managers. This would remove any uncertainty as to the propriety of impact investments amongst institutional investors.

The introduction of incentives in the form of tax relief would further enhance the risk/return profile of such investments and help to unlock funds that might not otherwise be directed to the social sector.

As well as building an enabling environment that fosters impact investment (see the international initiatives below), government can play an active role as a constructive commissioner of impact investment. It can shift from the mindset of a purchaser of services to that of a commissioner of outcomes. Such a shift could apply across all levels of Australian government – federal, state and local – as has occurred in the UK.

In a recent submission to the Australian Financial System Inquiry, SVA advocated government support expressing the belief that no single, fixed international template could or should be adopted. Instead, SVA recognises that the international experience offers a series of lessons that could be learnt from and acted upon.

Some of the international initiatives that Australia could draw from include:

Supply

- The UK's Charity Commission released guidance in 2012, directing charity trustees that ethical considerations may be relevant in investment decisions. A recent UK Law Commission Consultation Paper further proposes the introduction of a new statutory power giving charity trustees greater comfort that social investment is within their authority.

- The UK has recently introduced incentives for social impact investment in the form of tax relief for private investment in charities, social impact bonds, community interest companies and community benefit societies.

Intermediation

- The UK's Big Society Capital, the first dedicated social ‘investment bank', was armed with £400m from England's dormant bank accounts and £200m from the four largest UK high street banks. Its aim is to develop an effective and efficient intermediary market and as such only invests in intermediaries.

Demand

- The UK's £10m Investment and Contract Readiness Fund is dedicated to supporting social ventures in acquiring the skills to raise investment and compete for public service contracts. It offers grants of between £50,000 and £150,000 to ambitious social ventures, which aim to raise at least £500,000 of capital or want to bid for contracts worth over £1 million.

- The UK's £10m Social Incubator Fund aims to drive a robust pipeline of start-up social ventures by increasing the focus on incubation support, and attracting new incubators into the market. The Fund aims to increase the finance available at early stages of enterprise where the financial return is too low, and/or the financial risk is too high, for Big Society Capital and other investors. There is an expectation that each social incubator supported by the fund would offer a portfolio of intensive support over a time-limited period, with the capacity to help at least 50 social ventures over the life of the project.

Each of the initiatives outlined above could be adopted in the Australian context, many with little cost to government. In some instances (e.g. SBBs), the ultimate focus is on driving down the cost of achieving social outcomes.

However government can't (and shouldn't be expected to) do it alone.

Investors

On the supply side, there is an opportunity for philanthropically minded investors – foundations, trusts, private ancillary funds or high net worth individuals – to stump-up seed funding or catalytic first-loss capital to pave the way for institutional co-investors to participate in impact investing deals. Potential investors that are unsure of how and where to identify prospective impact investments should also engage with intermediaries, which can leverage their relationships in the social sector to identify investment opportunities that match the investor's needs.

Conclusion

Sir Ronald Cohen likens the state of the market today to that of the venture capital market in the 1970s. Cohen predicts that ‘the capital flows into impact investment are potentially huge', but that it could take another 10 to 20 years for demand for capital to fully respond to increased supply and gather great momentum.

While in hindsight, initial projected growth rates for the market were perhaps a little bullish, once the challenges have been overcome, the potential disruption of impact investment could well be ‘a very big one'.

This article has been reproduced with permission from SVA Consulting Quarterly.