When the thing is not the thing

One night in 1975, Australian psychologist Don Thomson found himself at the centre of the very problem he was researching. A day after appearing on national television, where he enlightened his audience on the unreliability of eyewitness statements, he was charged with assault and rape.

His alibi was good. Hundreds of thousands of people had seen him on live television at the time of the alleged attack. And one of the people appearing with him on the box that night was an assistant commissioner of police. Still, the officer taking his statement didn't buy it: “I suppose you've got Jesus Christ, and the Queen of England, too.”

Investigators eventually worked it out. The rapist had attacked the victim as she was watching Thomson on television. She had confused his face with that of her assailant. Thomson was released, no doubt more convinced of the veracity of his experiment's conclusions.

Research into the unreliability of eyewitness reports supports the notion that seeing and believing have less to do with each other than we think.

Psychologists call it misattribution, one of the seven sins of memory. Misattribution occurs when we use information to make inferences about the causes of behaviour or events, despite there being no link between them.

Remember all that fuss in the '90s about false memory syndrome? Well, it turns out that the memory of an event can be influenced merely by imagining it. And the more we imagine it, the more likely we are to believe it to be real (Mazzoni and Memon, 2003).

Language can also influence memory. A 1974 study had participants view films of minor car crashes where nothing broke or shattered. After being asked how fast the vehicles were going when they “smashed” into each other – as opposed to “hit” – participants were more likely to describe speeding and shattered glass they never actually saw.

More serious consequences are reported by the US-based Innocence Project. Between 1989 and 2014, 72 per cent of wrongful convictions were based on eyewitness testimony. As Professor Tim Valentine told The Guardian, "Witnesses' recall can be influenced by information acquired during an investigation. Just repeatedly questioning a witness tends to increase their confidence in both correct and mistaken answers.”

It's a popular misconception – a misattribution in fact – that human memory functions like a computer. Instead, it's malleable and prone to revision following the ‘recorded' events.

If what we see with our own eyes can't be relied upon to recount an accurate assessment of events, imagine what fun you can have misleading people with press releases?

Take the recent decision by Commonwealth Bank to eliminate fees on ‘foreign' ATMs. After several scandals, the bank needed some good publicity. The misattribution was in the bank thinking the average person is just as driven by money as a mortgage broker. Removing the fees looked like a cheap bribe, rather than an act of goodwill, reminding us of a cynical, quid pro quo, money-driven culture.

Broker 12-month share price targets are another example. Novice investors use them to calculate how much they'll purportedly make in a year's time. You can understand their thinking. Brokers are smart and almost every broking house provides them. What would be the point if they were useless?

Here, the misattribution is with the client. The number is useful to the broker because it gets the client to trade, potentially opening the door to more transactions. They've calculated it to be worthwhile, even at the expense of leading clients astray. The misattribution is in the client thinking their interests coincide with those of their broker.

Garry White, chief investment commentator for UK broker Charles Stanley, gives us the honest truth: “We do not issue price targets as we deem them to have too many variables to be accurate, market fluctuation being the biggest driver.”

Once you start thinking about this stuff there's no end to it. Have you ever taken a rising share price as confirmation of your decision to buy a stock a few months previously? That's misattribution. Our decisions will be validated years down the track, when the market has ceased to be a voting machine and become a weighing machine.

At the level of the individual, misattribution is normal and contained. But in the political and economic spheres it can be more damaging.

A study published by the Journal of International Business and Economics in 2012 supports Garry White's argument that emotion plays a far bigger role in investment decisions, concluding that “equity and bill prices are positively correlated to investor mood, with higher asset prices associated to better mood.”

The closing remarks of the paper are especially challenging for believers in the efficient market hypothesis: “Supposing that the individual is rational in his decision (supposition that shapes the neoclassical theory) has been consistently refuted in empirical work, validating the hypothesis that cognition and emotion have direct implications on how the individual decides and allocates his assets.”

Forget rationality – emotion, mixed with faulty memory, is the far bigger driver of markets.

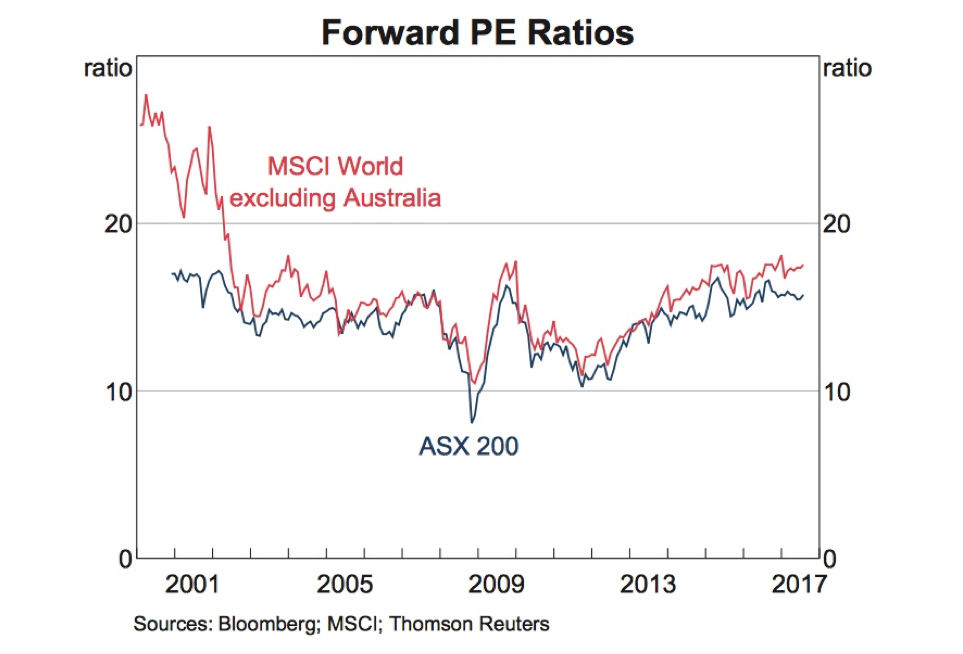

Right now, everyone's feeling very good. Check out this chart, showing the forward price-to-earnings ratio for the ASX 200 and the MSCI (exc. Australia) from the most recent RBA data pack.

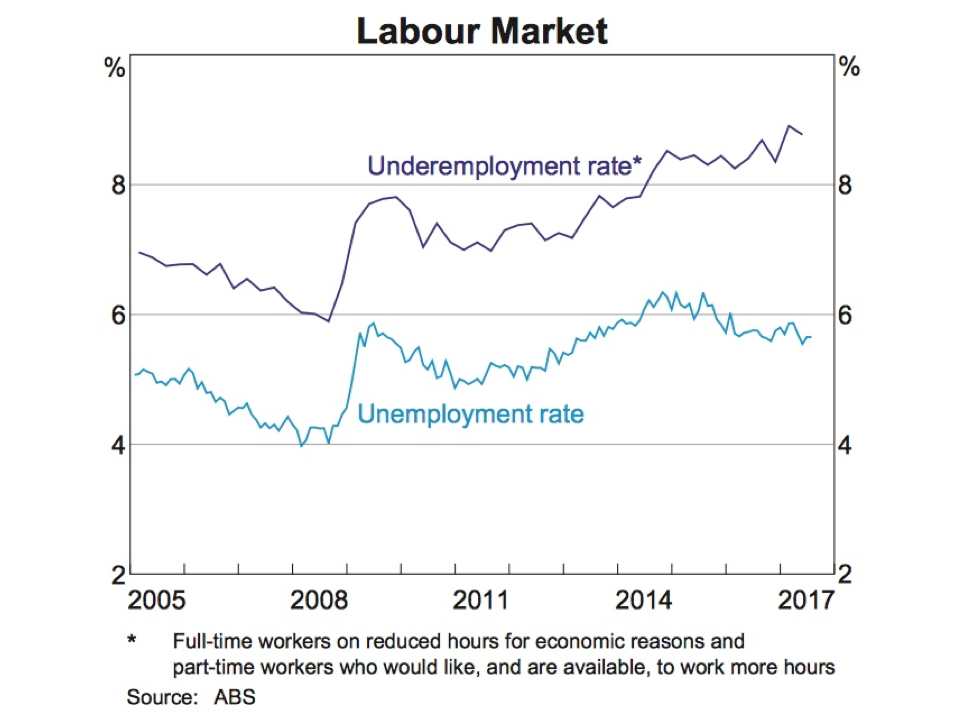

The unemployment rate, or the misuse of it, is another example. The media has schooled us into taking the headline number and drawing conclusions about the general state of the economy. Low inflation, low unemployment, good economic growth? Tick, tick and tick.

But too often we misattribute one number as a proxy for complex social and economic circumstances. The chart below shows the headline unemployment rate (the light blue line) falling in recent years, for which politicians have been eager to claim credit. The purple line above it is increasing, and that's a measure of the number of people with a job but wanting more hours. That's a big problem masked by a single number.

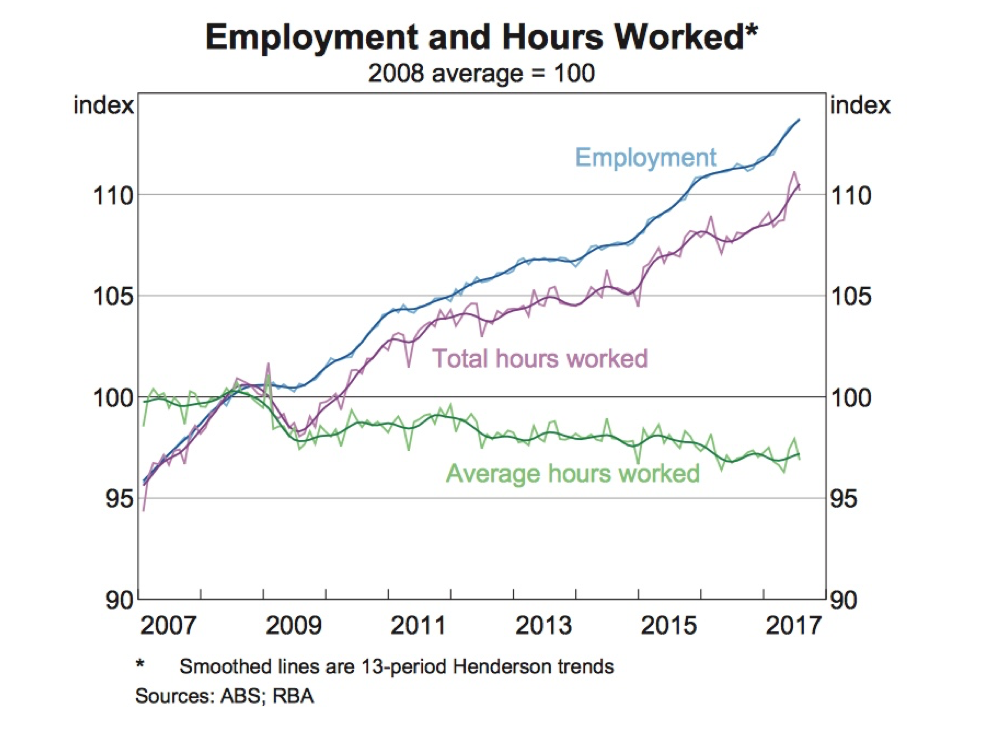

This chart below gives an even better indication. While employment and total hours worked has grown, as you'd expect with a rapidly growing population, average hours worked has been steadily falling. This is a major source of angst, and concern, for those who can't get by on a part-time job. It's a loss of economic output for all – especially when you consider the ABS determines a person as ‘employed' if they work just one hour a week. Nothing in the headline unemployment rate hints at the scope of this problem.

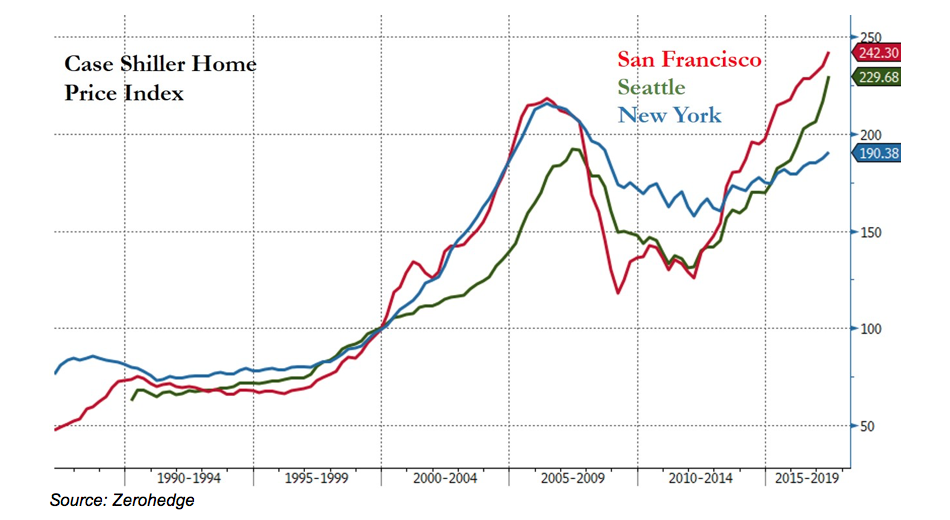

Finally, let's take a quick trip across the Pacific to Seattle, where Loftium is taking advantage of sky-high house prices and rents in the city. The company's business model is premised on a giant misattribution by customers.

Loftium targets potential homeowners that can't scrape together a deposit, which would be almost everyone in Seattle under 40. It contributes $50,000 to a home deposit on the proviso that one room is rented out on AirBnb for 357 days a year, for up to three years after purchase. In return, Loftium takes 30 per cent of the rental, but does provide nice toiletries for guests. Very thoughtful.

Let's pretend this kind of business model has nothing to do with the excesses of pre-GFC USA and look instead at where the misattribution occurs.

The young buyers, many of whom may not recall the last housing market crash – or believe it's different this time because of, err, Amazon – think they're getting a leg up into a rising housing market, the price of which is a tourist in the spare room. Fair enough.

But what they're really getting is a home equity loan at an absurd interest rate that helps a finance company skirt the regulations which were implemented to reduce the risk of another housing market crash.

It's a darkly brilliant model that could be a real winner with the money launderers recently shut out of Commonwealth Bank's intelligent teller machines. Ian, there's an opportunity here somewhere. Get on it.

Enjoy your weekend. Have a bubble tea on me.