The Eurozone turnaround

The summer rains have come early to the north coast of NSW. With the ground lumpy and cloggy underfoot, the builders' Blundstones are performing some impromptu landscaping in what the neighbours call the never-ending-renovation.

Europeans, especially in Greece and the UK, to say nothing of the burgermeisters in Brussels and Frankfurt, will be familiar with the feeling of being bogged down. The Eurozone has been around for 18 years, growing at an average rate of 1.6 per cent per year.

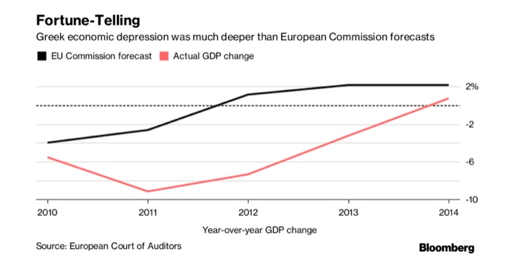

The latest data on the Greek bailout hardly challenges this history. You'll never believe it, but things didn't work out as planned; the recession was much deeper than the EU forecast.

This might have had something to do with the 14 different austerity packages introduced over the past seven years, conditions of the loans designed to reduce the country's debt, which now appear to have the opposite effect.

There are many reasons for it but I'd put the problem of currency unions at the top of my list. Greece's recent experience reveals why. Had Greece stuck with the drachma, once investors found out it was cooking its books, ably assisted by Goldman Sachs, it would have fallen. That would have been an automatic stabiliser to hasten the recovery.

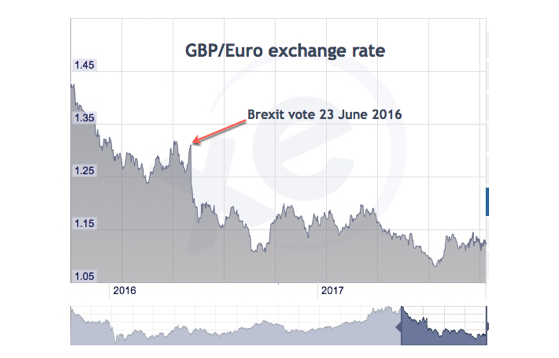

The UK sterling, in the aftermath of Brexit, provides evidence to support the theory. UK growth next year is forecast to be just over 1 per cent, one of the lowest figures in Europe. Yesterday, the Institute for Fiscal Studies warned the UK was “in danger of losing not just one but getting on for two decades of earnings growth”. So, not good.

And yet on Tuesday this week, the Confederation of British Industry reported that the order books of UK manufacturers were the highest they've been in 30 years. This chart, showing the decline of the pound against the euro, explains why.

A floating currency is a counterbalance, encouraging growth via a lower exchange rate when the economic picture looks grim. A currency union offers no such flexibility to its members, meaning the devaluation must be ‘internal' – higher unemployment, lower wages, reductions in government expenditures, and potentially, higher taxes.

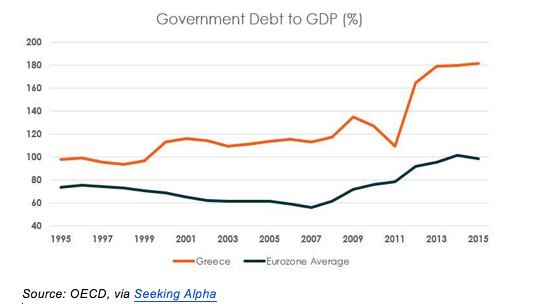

A floating currency helps a country to absorb economic shocks. Without one, ordinary people must carry the load, which has happened in Greece. Since 2011, government debt to GDP, as shown in the chart below, has actually increased. Instead of a short sharp shock, the recession in Greece has been deeper and longer lasting. Nice work Brussels, you put the Chicago school to shame (that dig is for the wonks among you).

Finally though, after six years of pain, the deficit is coming down and the country is returning to money markets to raise debt, most recently in July. It's possible that the unsettling brinkmanship we've seen in previous negotiations is diminishing, along with the chatter around a Eurozone breakup (except from yours truly).

If so, investors will be relieved because Europe is cranking. Eurozone growth should hit 2.2 per cent this year against a forecast of 1.4 per cent. Maybe it's London bankers jumping on the Eurostar to find a pad in Paris or Frankfurt, but investors should take what they can get. With inflation in the EU out of the deflationary danger zone and unemployment falling in each of the past four years, Reuters has called the region “the surprise economic star of 2017”.

Maybe the burgermeisters have learnt something from Greece's pain after all. Paola Subacchi told Reuters this week that there is now “an understanding – even in Germany – that demand needs to be supported... you can't just sit and wait for growth”. That's progress I suppose, even if it has taken eight years. I just hope I don't have to wait that long for a new deck.

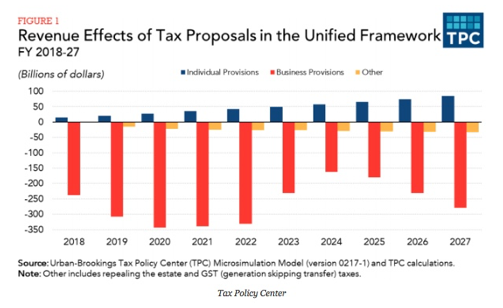

As Europe slowly bends towards the light of evidence and experience, the US turns ever faster away from it. After banging on about government debt for 30-odd years, in the grand tradition of Reagan and Bush, Trump's tax plan can only exacerbate the problem. Two charts from the Tax Policy Centre explain why.

The first, below, covers the tax revenue impacts of the changes based on taxpayer type, revealing that taxes on individuals will actually increase in favour of massive corporate tax cuts.

The effect on government debt is dramatic. Add up all the red and yellow blocks, subtract the blue blocks, and you've got yourself the net effect on tax revenues. The Tax Policy Center estimates this to be a loss of $US2.4 trillion over the first decade and $US3.2 trillion over the next.

If the evidence supported the claim that higher after-tax corporate profits led to increased investment, higher productivity growth and higher wages, that might not be a problem. Unfortunately, there is no evidence to support the proposition. Instead, additional profits tend to be recycled back to shareholders as dividends and share buybacks.

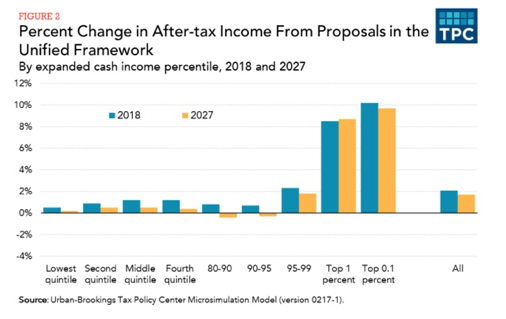

This may explain why the S&P 500 is up 18 per cent in the past year compared to about 10 per cent for the ASX 200. Their corporate tax cuts are bigger than ours. The market is already pricing in the passage of a bill that will return billions to shareholders. What it probably isn't pricing in are the long-term effects on aggregate demand embedded in the chart below.

By 2027, according to The Tax Policy Center, “about 80 per cent of the total benefit [of the personal tax cuts] would accrue to taxpayers in the top 1 per cent, whose after-tax income would increase 8.7 per cent”. For the average one percenter, that's a saving of $US129,030. Not bad. Down the income scale, “taxes would rise for roughly one-quarter of taxpayers, including nearly 30 per cent of those with incomes between about $US50,000 and $US150,000 and 60 per cent of those making between about $US150,000 and $US300,000”.

Along with hard work and thrift, Adam Smith believed in the concept of enlightened self-interest, that furthering the interests of others ultimately serves oneself. US legislators really seem to get the self-interest bit, but seem to miss the qualifier. To them, Smith is someone to be quoted, not read.

All empires experience decline; the historical tide of democracy and the second world war did for French and UK colonialism; the Spanish empire was lost to military conflicts. Elsewhere and in another time, the Romans, which had grown fat on slave labour, were undone by overreach, corruption and the rising threat of the East.

The US empire, different in form but just as powerful, is surely the first to be taken apart from the inside. In Beijing they must wondering how they got so lucky. Like the Russians, they're putting everything on orange and coming up... well, I just won't say it.

US corporations, meanwhile, have sniffed the wind. Why bother investing when the middle classes that buy your products are likely to have less money in future?

Valuations in US markets suggest investors understand the short-term effects of this policy well enough but are not yet thinking through the long-term impacts. It's as if recency bias has become a virus, where we listen to some dimwit CEO or fund manager succumb to blind optimism as a way of justifying the prices they're paying for the profits they're about to make.

Take the head of American Airlines. In an imperious display of historical ignorance and lack of regard for his future employment prospects, Doug Parker recently claimed that American was never “going to lose money again". Doug, apparently, has forgotten that he runs an airline.

Take recently ASX-listed SelfWealth, a trading platform that wants to become “the Facebook of investing”. In financial year 2017, SelfWealth produced revenues of $1.7 million and a loss before tax of $3.2 million. This week it raised $7.3 million to help build its 1690-strong client base. I can fit almost as many kids in a Toyota Tarago. Now that's a feeling.

Compared to Updater, which Intelligent Investor examined in May, SelfWealth's market capitalisation looks reasonable. Updater wants to “redefine the moving experience” in the US but is doing a far better job of redefining valuations. The company claims not to be chasing revenue and is doing a fine job of it. While Updater processes about 12 per cent of all US moves, its revenue in 2016 was $US600,000. The current market cap is just shy of $400 million.

Meanwhile, in the US the NASDAQ is awash with companies with billion-dollar market caps losing billions of dollars a year. Last weekend, The Australian claimed there were a dozen NASDAQ-listed stocks trading at earnings multiples at 240 or more. If that's not enough risk for you, try cryptocurrencies.

The challenge is staying sane while everyone else wins big on momentum trades by defiantly ignoring the risks they're taking. Good luck with that. Personally, I'll be standing aside, watching the cricket and fiddling with my new iPhone.

Enjoy the weekend.