China crash: Are we there yet?

Five years ago we wrote a special report titled The Coming China Crash. The argument was lengthy but self-explanatory. There was trouble ahead and it was time to prepare. A portfolio of China crash-resistant stocks was proffered, which, unsurprisingly, has performed well since.

Still, the tumultuous events of recent weeks offer no sense of vindication, only the opportunity for further confusion. Let's try and unscramble the egg.

What just happened?

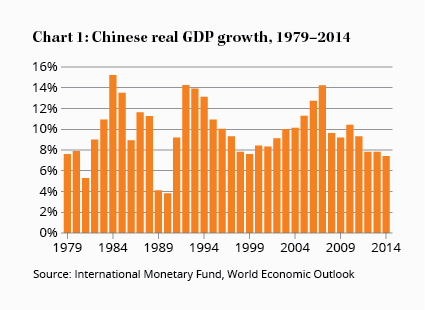

Everyone got really scared that the China growth story was over. Since 1980, Chinese gross domestic product (GDP) has risen almost 2,500%, driven by average annual GDP growth of 10%. Due to the power of compounding, annual growth three times the rate of developed Western economies has led to cumulative growth 15 times higher. China has experienced one of the great booms of all time.

No economy can grow at such a pace forever, which is why Chinese leaders are trying to transition from an investment to a consumption-led model. The big question is 'how'. Recent data has been poor. Exports and imports are down and manufacturing activity is weak, prompting an unexpected currency devaluation and a rapid reduction in interest rates.

Western markets usually price in the probabilities of such moves in advance but in this case have only recently awoken to poor data, aided by the vertiginous falls in Chinese sharemarkets. The Shanghai Composite Index peaked on June 12 and has since fallen 38%. Still, it remains 37% above where it was this time last year.

Do recent market falls tell us something useful?

Not really, but Chart 1 might. Never has such a large, disparate country industrialised at such a pace. Nor has it been achieved within a political system that demands political compliance in exchange for growing economic wealth.

It's hard to imagine how a country can grow at such a pace for decades without storing up a few problems. McKinsey estimates that Chinese debt has risen fourfold since 2007, most of it directed to a building boom. In Australia, housing construction accounts for about 8% of GDP. In China it's twice that.

Throw in decades of overinvestment in infrastructure, a huge shadow banking sector that has financed a speculative bubble, first in property and now in shares, plus endemic corruption and you can imagine the problems. The real concern is that China is now using bad debt to prop up its growth rate.

Large falls in Chinese markets spread to major western markets as fear that the great Chinese growth experiment was on the edge of collapse. Add in the fact that China is a greatly misunderstood stew of complexity with a clearly panicking leadership and you have a recipe for volatility but not necessarily understanding.

How are Chinese authorities responding?

With a bureaucratic mix of ineptitude and panic. During volatile periods in the west we ban short sellers; in China they throw them in jail. Authorities blamed the falls on meddlesome foreigners and forbade banks and brokers from selling stock. Imagine that?

We should be concerned. If that's how China reacts to a simple stock bubble, how will it handle a genuine financial crisis? And can it deflate a speculative bubble without inducing one?

The bigger issue – of reducing the country's reliance on debt-financed investment in favour of consumption without sacrificing economic growth altogether – is likely to prove even more challenging.

Whenever the Chinese have faced problems in the past they've reverted to policies that have exacerbated the underlying problem. A trillion dollar investment program in 2008 made the issue of under-productive investment worse and the transition to a consumption-driven economy harder.

In recent months we've seen authorities reach for policies from the same playbook: even lower interest rates, devaluation and potentially further monetary stimulus. These may help alleviate the short-term problem of lower rates of growth but push the prospect of a transition to a more mature economy further away. As Martin Wolf wrote in the FT recently, 'Maybe Mr Market has grasped how difficult this is going to be.'

So the transition will be painful?

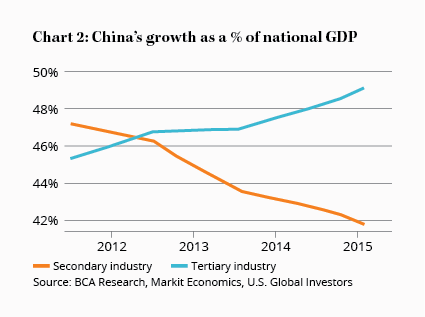

It's too early to say. China certainly has its problems but with an unpegged exchange rate (take note euro zone) and huge foreign exchange reserves the country has a few cards up its sleeve. Plus there's some evidence of a transition away from investment and towards consumption already underway, as Chart 2 from BCA Research shows.

As a percentage of GDP, non-manufacturing is growing. The Chinese are spending more on service industries like finance, insurance, tourism and entertainment. But the change isn't happening fast enough to prevent the decline in GDP growth.

The big issue to watch is property because housing and land are the collateral on which the financial system rests. Whilst we've long made the case for a property bubble, The Economist reports that 'house prices have perked up nationwide for three straight months' whilst Frank Holmes of US Global Investors calls the market 'robust'.

But really, who knows? Everyone's hoping for a smooth transition but as the old saying goes, 'predictions are difficult, especially about the future'.

How much should Australians worry about a China crash?

The Guardian has a fascinating infographic on the exposure of major economies to a China slowdown. The US and Europe don't have much to fear but New Zealand and Australia do. For the first seven months of this year, Chinese imports fell 14.6%. If that figure held for the remainder of the year that would account for a 1.7% fall in our GDP. Paul Krugman doesn't see that as catastrophic:

'These kinds of adverse shocks of exports always hurt, but its only catastrophic if either you have no recourse – so if [for example] you've given up your own currency then you're in trouble, and if you're very vulnerable financially; [or] if you're very heavily indebted in foreign currency then you're vulnerable. But last I looked Australia has neither of those characteristics.'

Luckily, our dollar is at six-year lows and despite the scaremongering around our debt, it's quite manageable, offering enough room for stimulus if required.

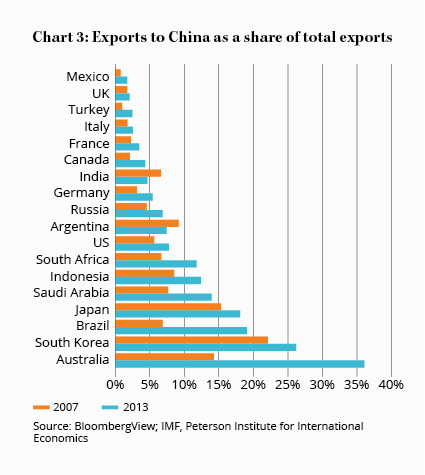

Now consider Chart 3, which shows that Australia's exports to China have grown from about 14% of total exports in 2007 to 36% in 2013.

China represents about 5.5% of our total GDP. The latest GDP figures, which showed quarterly growth of just 0.2% on the corresponding period last year, reveal the extent of our exposure. And yet the Australian economy isn't going out backwards. Dwelling construction was up 7.4%, agriculture was up 4.1% and household consumption rose 2.5% compared with last year. The slowdown in our economic growth is due almost entirely to the 6.9% fall in capital expenditure, which is largely resources based. The headline figure wasn't good but behind the numbers we're doing okay.

What are the portfolio implications?

It's too late to be getting out of resources and China-exposed investments. We've had years to prepare for that and have been advising members to do it since 2011. In fact, now might well be the time to get on the front foot.

The prices of resources stocks appear to already be pricing in a China slowdown, if not a crash. Commodity prices have collapsed and projects are being cancelled, taking capital expenditure with them. This leaves us in the strange situation of adding BHP Billiton, yielding around 7%, to our Income Portfolio.

Of course, we're not ruling out the possibility of a local recession (a subject for a column next week) but with the upgrade of South32, and Rio Tinto currently being worked on, you can see our view, at least on the big, high-quality stocks in the sector.

Finally, we'll take the opportunity to issue the usual advice about dealing with the risk of recession: don't try and time the market; hold some cash; welcome the downturns as opportunities to buy high-quality businesses at cheap prices; and don't be overexposed to the Australian economy, just in case.