Can you afford to live to 104?

Key Points

- Saving for retirement is often based on life expectancy, not life potentiality

- Many investors will outlive their savings

- A few simple strategies and products can help reduce your exposure

Background

Time in the market: Strategy or slogan? explained why time in the market doesn’t cure all ills. For those at or near retirement age, time is even less help. It may even be your enemy.

First, there’s longevity risk—the risk of you outliving your savings. Second, retirees are more exposed to the ‘sequence of returns’ than other investors and can’t afford an early hit to capital. They can’t go to cash either, as the low returns and inflation bring longevity risk back into play. What can one do?

Longevity risk

If you outlive your savings it’s because you either don’t have enough in the first place, the savings that you do have perform poorly, you spend too much, or you live longer than you expect. Yes, this is a brutal but necessary conversation.

Go to ASIC’s Moneysmart website or a financial planner and they might tell you that $1 million of super will give you a comfortable retirement. That’s true, if you’re 65 years old and only live another 20 years.

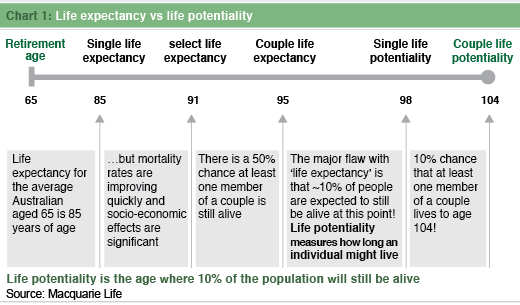

Trouble is, roughly 50% of Australians will live beyond the average life expectancy and many well beyond it. Chart 1 shows the difference between ‘life expectancy’ and ‘life potentiality’ (the age 10% of 65-year olds will reach). Alarmingly, 10% of couples will see one member live past 104!

So, you’ve done your retirement calculations based on being retired for 20 years but one-in-10 couples will see a partner living for twice that. This has a huge effect. What you think you need might only be half to three quarters what you actually need.

The ‘sequence of returns’ issue

If you’ve already cottoned on to this problem, perhaps you’re targeting a higher rate of return to compensate for the additional life potentiality. This leads to the second ‘time-based’ problem.

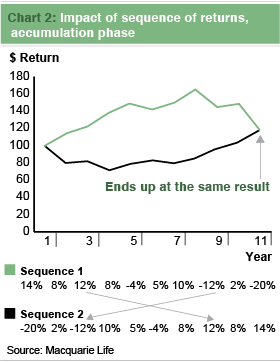

In the ‘accumulation’ phase (saving rather than spending), the sequence of returns doesn’t matter. If you start with $100 and generate a 50% return over ten years, you will finish with $150. Whether the return is consistent each year or arrives in one 50% lump in the 10th year doesn’t matter.

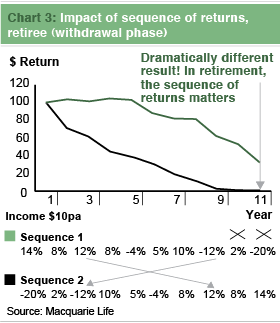

For retirees in the ‘withdrawal’ phase it matters very much. They’re more exposed to volatility of returns and, as a result, usually have a more conservative portfolio. An investor in the withdrawal phase will struggle to recover from poor performance in the early years.

Consider an investor in accumulation phase starting with $100. If consecutive annual returns are minus 10% followed by positive 11.11%, overall returns will be zero and the investor will finish with $100. But an investor withdrawing $10 each year won’t finish with $80, they’ll end up with $78 to $79 (depending on the timing of the withdrawals). Compared to the accumulation investor, the withdrawal in the first year means the positive performance is earned on a lower capital balance.

Charts 2 and 3 show how this phenomena plays out over time and its potential impact on ‘longevity risk’. Poor early year performance can cut years from the life of your savings.

Cash and bonds are often proposed as the solution to the sequence of returns risk but are they the answer?

Russell 10/30/60 rule

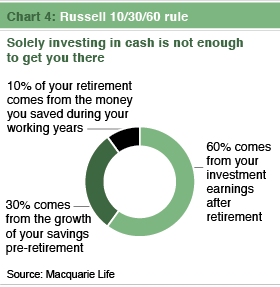

Chart 4 demonstrates the ‘Russell 10/30/60 rule’. It says that 60% of your retirement income comes from your investment earnings after retirement.

That presents a conundrum. The lower returns on cash and bonds make it difficult to achieve the ‘Russell 60%’ and increase the risk of you outliving your savings. But investing in growth assets exposes you to the sequence of returns problem.

Most investors, often unwittingly, take the longevity risk, minimising their exposure to the sequence of returns risk but increasing the chance of chewing through their super balance too quickly. That’s understandable—most of us would struggle to plan for life at 104—but it will leave many investors short.

Potential solutions

There are some ways to mitigate longevity risk without over-exposing yourself to volatility:

-

Lower your living standards. If you’re prepared to lower your living standards you’ll have less to worry about. It’s likely there will always be an age pension and associated benefits, although it’s likely to be less rather than more generous than it is today. Either way, this wouldn’t be a satisfactory outcome for many retirees.

-

Save to life potentiality. Rather than saving to ‘life expectancy’ you could save on the assumption you’ll live to a century or more. That means you might need to increase your contributions by as much 50% compared to a life expectancy-based approach.

That means you’re saving for possible rather than likely needs. We recommend allowing some ‘margin for error’ in your savings calculations but this approach replaces a potential problem (outliving your savings) with a certain problem (having to save more now). Again, it’s not ideal.

-

Fallbacks. Allowing some ‘margin for error’, adopting a more growth-oriented portfolio and having a fallback option will help alleviate longevity risk but reduce your exposure to poor performance. The fallback might be returning to work (on either a temporary or part-time basis), downsizing your home to free up equity, having the ability to reduce your income needs, or any combination of these options.

-

Delay retirement. The average person’s working life is a smaller proportion of their total life than it was a century ago. In fact, some retirees may be retired longer than they worked. So why not increase your working life?

An extra three years of full-time work now might add five to 10 years to the lifespan of your savings.

-

Lifetime annuities. There aren’t many products that address ‘longevity risk’, but ‘lifetime annuities’ do. These allow you to purchase an income stream—typically inflation linked—for the remainder of your life, with the issuer taking the risk that you live to 100. They’re not to be confused with term annuities, which are essentially deposits, or bonds, that do nothing for longevity risk—they simply pay you back interest and principal over a fixed timeframe.

Lifetime annuities have two main drawbacks. First, their returns can be quite low (depending on your age, you might receive considerably less than a bond or term deposit). Second, if the recipient dies early, there’s no ‘balance’ paid out to the person’s estate—the issuer simply stops paying. This is the trade-off for the insurer taking the risk of paying you past average life expectancy.

Oddly, lifetime annuities aren’t popular in Australia, although life insurance companies such as Challenger and Comminsure (part of the Commonwealth Bank) do have some products. Term annuities, term deposits and even hybrids are more readily available.

Investors are put off by low returns and the lack of a lump sum payout to their estate. But in an age where people regularly insure their homes, contents, vehicles, travel plans, income and life, why not insure against the possibility of ending up with nothing except the Government pension?

If you are considering lifetime annuities, remember that you’re taking credit risk on the issuer. APRA regulates life insurance companies but that’s no guarantee—remember HIH. Don’t put all your eggs in one basket. Spread the risk.

-

Guaranteed Retirement Income Products (GRIPs). GRIPs aim to give investors the best of all worlds, allowing you to be invested in a portfolio, including equities, from the outset but also guaranteeing a minimum level of income for life. GRIPs are offered in Australia by Macquarie (Lifetime Income Guarantee) and AXA North (Protected Retirement Guarantee).

Lifetime annuities are a bet with the issuer on how long you live compared with average life expectancy. GRIPs take an insurance approach to the longevity issue. Each year your ‘account’ is effectively charged an insurance premium. Your ‘fallback’ guaranteed minimum income might be less than a lifetime annuity but a GRIP offers you the chance at equity returns (and an increase in guaranteed income) plus an account balance which can be paid to your estate.

This should give you a reasonable result across a range of scenarios, although never the best result due to the cost of the insurance premium. Together with the aged pension for those that qualify, it guarantees a minimum ‘base income’. The downside is that you remain exposed to early-year equity market performance. A few poor years of sharemarket performance might see your account balance fall to the level where you get the minimum income, rather than long term equity returns.

Like annuities, you have credit risk on the issuer, so don’t go putting the bulk of your retirement savings into the one product.

None of these options are a silver bullet. But incorporating one or more into your retirement strategy can help reduce your exposure to longevity risk, without increasing other risks (although you have to trade-off some current living standards). If there’s an increase in demand for lifetime annuities and GRIPs more products will be developed, giving you more choices to address the issue.

Final thoughts

Volatility has driven many investors away from the sharemarket altogether. But this means they’re simply reducing one form of risk—volatility—and increasing another—longevity.

MoneySmart considers the aged pension as a reasonable fallback option but many investors don’t. By making a few small trade-offs today you can significantly reduce the possibility of you outliving your retirement savings.