Bye, bye Miss American Pie?

It may be heretical to say so, but I find Warren Buffett a bit of a bore. His folksy style might suit the communication of his message – and what a message – but something about it grates on me almost as much as the fawning media coverage he attracts.

But, his business partner Charlie Munger? Now there's someone worth a trip over the Pacific.

So it was that on an early morning in May 2010 I found myself in an English pub in Pasadena, a plate of sausages, bacon and eggs and a pint of bitter before me. The breakfast of champions was ideal preparation first for Tottenham's vital game against Manchester City, thoughtfully screened on banks of TVs in the bar, followed by the Wesco AGM around the corner.

Munger, less eager to please than Buffett, was just as engaging. When asked a question on the US's ability to build on its economic power, his reply has stayed with me. “Well, we have the best universities. The smartest people from around the world want to come here. And in California, at least the weather is nice. I don't see why not.”

The quote popped into my mind this week whilst reading a review of economist Tyler Cowan's new book, The Complacent Class: The Self-Defeating Quest for the American Dream. The now mandatory wordy title gives it away, but this quote does a colourful takedown of Munger's position:

“Over the last forty years, America has become the land of the ossified … static, crumbling on the edges, but soothed. In Colorado and Washington, even stoned. Content and comfortable with 5G streaming but tired standards of living, a virtual paradise, but a physical purgatory. NIMBY'ed into an exitless cul-de-sac of repeating repeal and replace policy debates. Trigger-warned in a safe space with heart-emojis all around. Child-proofed for $60k a year in tuition. Segregated by income, zip code, and college degree. Ask your doctor. Read our ad in Good Housekeeping. Did you get the Eventbrite from the protest planner for today's riot?”

How to ruin the start of a good weekend, right? Or are you still thinking about a full English breakfast?

To enforce the point, a post this week on Cowen's excellent blog Marginal Revolution witheringly refers to a Bluetooth connected salt shaker called – what else? – Smalt, a “multi-sensory device” that “elevates the dining experience”. Please Lord, take me now.

Inert innovation like this isn't an aberration. A Silicon Valley start-up called Juicero has raised US$120m to produce a US$400 juicer that wields enough force “to lift two Teslas” – because, you know, a tonne of Tesla exerts more force than a ton of Ford. The purpose is to extract more juice from the vegetable bags supplied by Juicero.

Except it isn't. In a mini-scandal reminiscent of Theranos, which took investors for a more impressive US$400m, it turns out that squeezing the bags by hand produces as much juice as using the juicer. Look! My hands have Tesla power!

If this is what America's best-and-brightest can manage, doesn't Cowen's depressing description nail it? I'm cherry-picking, of course. Silicon Valley has created incredible value for investors. Google, Facebook, Amazon and Apple are global monopolies of incredible power and genuine disruptive force, as the journos being laid off at Fairfax might attest.

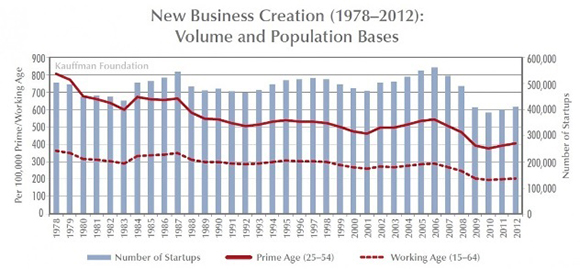

But, unfortunately for the US, they also employ comparatively few people and pay almost nothing in taxes. Their true social value is to skew our view of America's disruptive and innovative culture, which, the data indicates, is not going the way of more Amazons but even fewer Juiceros. This chart shows the trend in start-ups from 1978 to 2012 (the thick red line):

Source: Kauffman Foundation, via The Washington Post

Since 1978, the number of start-ups created by people of prime working age, adjusted for population growth, has halved. This wouldn't be the first time media coverage was inversely proportional to the availability of contradictory data, but it does highlight how Google and Facebook aren't tentpole companies in a dynamic entrepreneurial culture but totemic examples of something slowly ceasing to exist.

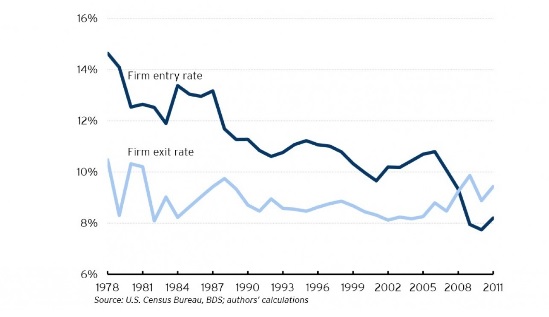

The inevitable consequence of an economy with more business deaths than births (see below) is the growing dominance of larger, older businesses.

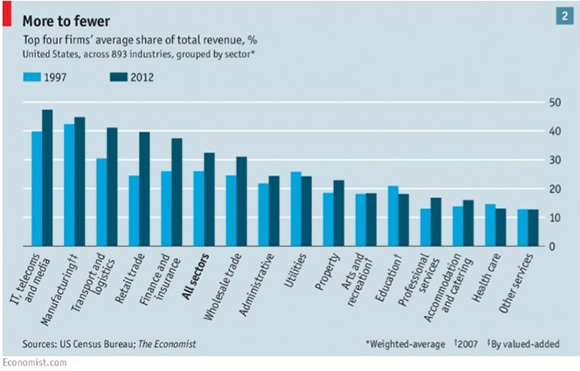

According to data compiled by Brookings Institute, in the early 90s companies 16 years or older accounted for 22 per cent of total businesses. By 2011, that figure had hit 35 per cent. The proportion of younger companies declined, especially among those less than five years old. This Economist chart makes a similar point, showing the industries where concentration has most increased:

The Economist goes on to say that, “Concentrated industries, in which the top four firms control between a third and two-thirds of the market, have seen their share of revenues rise from 24 per cent to 33 per cent between 1997 and 2012.”

Is this a problem? If the reduction in the number of firms in a sector isn't leading to a decline in competition, not necessarily. Unfortunately, the evidence suggests it is.

A 2016 paper by Grullon, Larkin and Michaely (Are US industries becoming more concentrated?) states that “more than three-fourths of U.S. industries have experienced an increase in concentration levels over the last two decades” and that “our findings suggest that the nature of U.S. product markets has undergone a structural shift that has weakened competition.”

The authors go on to say that “half of the U.S. industries lost over 50 per cent of their publicly traded peers” and that “this decline has been so dramatic, that the number of firms these days is lower than it has been in the early 1970s, when the real gross domestic product in the U.S. was one third of what it is today.”

Blimey. If there is disruption in US industry, it seems to be in the growing domination of large, established companies at the expense of start-ups and smaller companies that no longer offer much in the way of competition. You don't get that impression from the news though, do you?

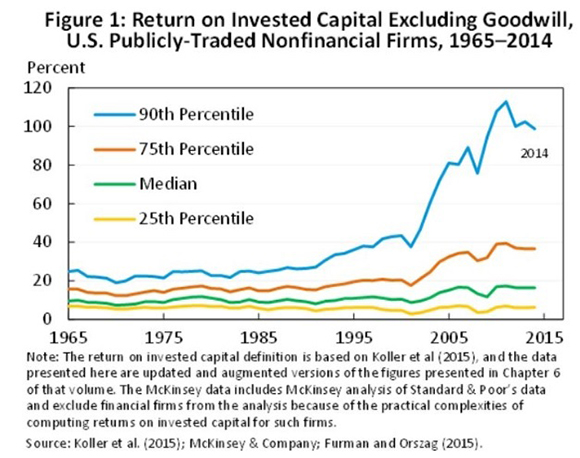

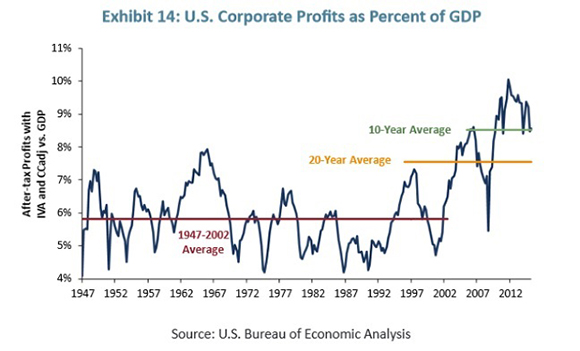

Let's take the next step: If major industries are becoming less concentrated and competitive, is there evidence of growing monopoly power? Well, not exactly, but there is this, via Urbanomics:

Note that this chart excludes privately held companies, which may offer a different picture, although I doubt it, and financial firms, where industry concentration has substantially increased (were it to be included I'd say the rising blue line would be even steeper). And there is this:

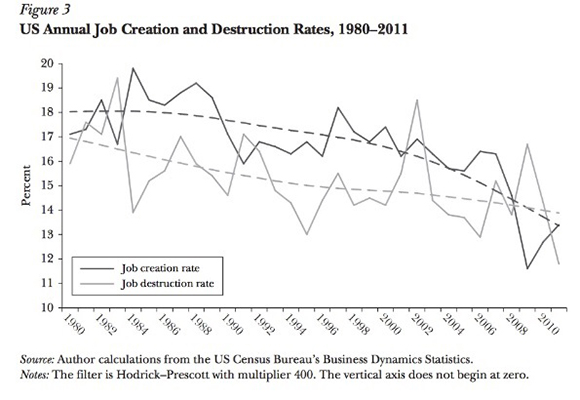

This isn't a problem for investors, at least not yet, but it is for ordinary Americans, who aren't sharing in the success. As US industry becomes more concentrated it employs fewer people. This chart, from the Journal of Economic Perspectives (my inner life is thrilling, I can tell you) shows that the rate of job destruction is now higher than the rate of creation, which is consistent with higher industry concentration and lower business formation:

It would be easy to conclude that bigger companies dominating many sectors are substituting labour in favour of capital, which would exert downward pressure on wages growth, and, as a result, are becoming more productive and profitable. But only two of those things are true.

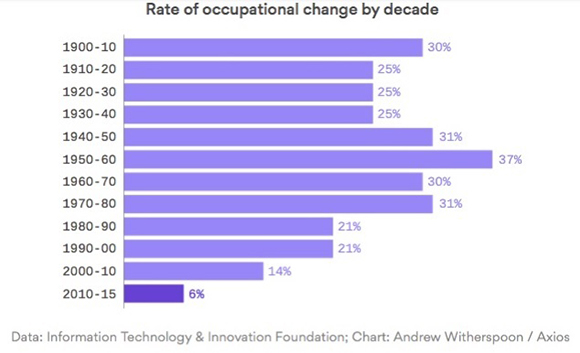

The so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution, as it turns out, is a mirage. This week the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation reported that, “technology is disrupting a record number of jobs”. Not a record high but, incredibly, a low.

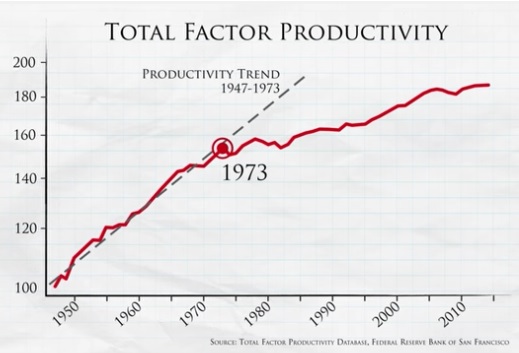

Its conclusion: “If there is any risk for the future, it is that technological change and resulting productivity growth will be too slow, not too fast.” The following chart bears out these fears. Despite Bluetooth connected salt shakers and Uber, the rate of growth in total factor productivity is actually slowing:

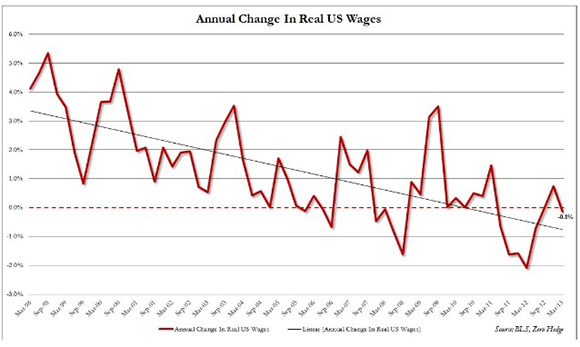

Meanwhile, the long-term trend in real wages growth (see above) looks like that annoying Coles ad with Casey Donovan.

So, business formation is down, industry concentration is up, taking corporate profits with it despite negligible productivity growth. Labour is not being substituted for capital to anywhere near the extent we are led to believe, but that isn't having much impact on real wages growth.

Little wonder that 20.5 million Americans have a drug problem; 30 million are on antidepressants, which has created a boom in happiness books (undermining the actual happiness of all of us when their authors pay us a promotional visit; 2.2 million are in jail (the US incarceration rate is higher than Saudi Arabia's); and for the first time in decades life expectancy is declining. Still, there's always Amazon, Google and Facebook, right?

It looks like Cowen is right. If the percentage of children earning more than their parents, by year of birth, has almost halved since the 1940s, surely the American dream is fading. For many, a $400 juicer that serves no purpose other than to snare millions from a VC's bank account is just rubbing their noses in it. America: Don't believe the hype.

As for Australia, where we have some of the same problems but nothing like the scale, I'd say we're still the lucky country.

Enjoy the weekend and plump for the full English breakfast and savour the fat. Unlike the US, for the vast majority, Australia still brings home the bacon.