Are ETFs a ticking time bomb?

The headline in the South China Morning Post summed up the fears around the sharemarket's latest obsession: Why the exchange-trade fund industry is a ticking time bomb. The precede saves the reader from wading through the detail. “History tells us that the kind of market dominance ETFs are enjoying never comes without a fall.”

An exchange traded fund (ETF) is a security that tracks a sharemarket index, bond or commodity. The fund usually owns the underlying assets, offering a slice of it to individual investors through an ETF. As they're tradeable just like an ordinary share, ETFs are easily bought and sold, making them a quick, transparent and cheap way to gain access to a range of assets that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive and time-consuming to acquire.

The options, too, are broad. Want to increase your exposure to international stocks? Try one of the hundreds of ETFs that track the Dow Jones Industrial Average, or the NASDAQ, FTSE, DAX, Hang Seng and Nikkei indices. There are equally expansive options covering the fixed interest and commodities markets.

Key Points

-

Rise in asset price more to do with bond rates than growth of ETFs

-

Synthetic, illiquid and derivative ETFs should be avoided

-

If ETFs do increase mispricing, then that's great for us

If you can think of it, there's probably an ETF for it. Think the retail sector will be killed by Amazon? Try the ProShares Decline of the Retail Store ETF. Fancying playing the accounting scandal thematic? There's the WeatherStorm Forensic Accounting Long-Short ETF, with a 1.62% expense ratio no less.

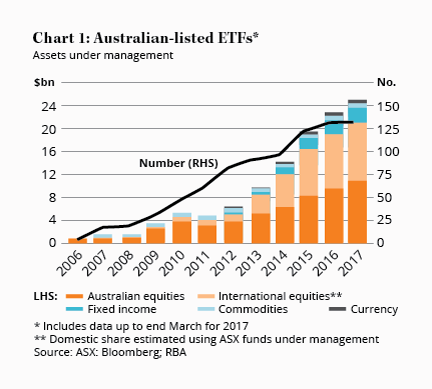

Since the first ETF was launched on the Toronto Stock Exchange in 1990, the global ETF sector now has grown to over 7,000 products accounting for US$4.4 trillion in assets, according to research firm ETFGI. In Australia, the Reserve Bank of Australia reports a similar trend, with a preference for equities over fixed interest and commodities not typically seen elsewhere.

Dumb money

Why the concern? The principal argument is that ETFs are unjustifiably increasing stock prices.

ETFs are essentially passive, investing regardless of fundamentals. As FPA Capital puts it, ‘When the world decides that there is no need for fundamental research and investors can just blindly purchase index funds and ETFs without any regard to valuation, we say the time to be fearful is now.'

It's arguable whether ETFs are making markets less efficient and more susceptible to crashes, which is what critics like FPA Capital believe. The effect of an additional billion dollars invested in the top 20 ASX-listed companies via an ETF is really no different from a direct investment. Shares in 20 stocks are purchased either way.

The position conflates the rise of passive investing and its lack of price discovery with the vehicle chosen to conduct it. ETFs may have enabled the move towards passive investing and some active managers that have underperformed may resent it – FPA Capital being a case in point – but the rise in asset prices over the past few years has probably got more to do with historically low interest rates than the popularity of ETFs.

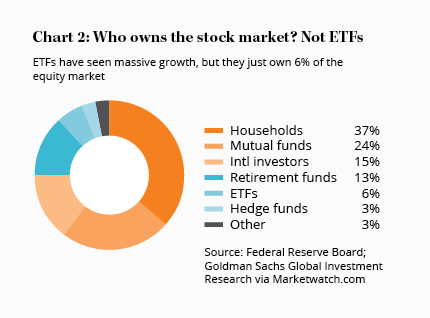

Moreover, active management is still a sufficient proportion of the market to enable effective price discovery. According to Morningstar, last year active assets still amounted to US$9.3 trillion while passive assets were US$5.3 trillion. And ETFs are only one part of the passive assets. Marketwatch, using figures from the Federal Reserve Board and Goldman Sachs, suggests that ETFs account for just 6% of the US equity market.

As Ed Rosenberg, head of ETF capital markets and analytics at FlexShares, says: ‘If correlations between stocks were at 90%, then you might be able to argue that ETFs were responsible, but that is not the case; they're closer to 40%.'

Blaming ETFs for the rise in passive investing and its attendant effects is like blaming a carmaker for a traffic jam. Only when central banks retreat from their role of propping up asset prices via monetary policy are we likely to see the true impact of ETFs on asset prices.

And it may not be much. As Ben Johnson, director of global ETF research at Morningstar, says: ‘ETFs and index funds don't cause bubbles, or crashes for that matter; investors do.'

Beware illiquid markets

Other ETF risks have more credence but are restricted to arcane areas of the market. The Reserve Bank of Australia in its June Bulletin highlighted three areas for investors to watch out for:

- ETF liquidity could fall in times of market stress;

- Synthetic ETFs pose counterparty risk, which means your ability to get out of an investment depends on a third party having the money and desire to permit it;

- ETF complexity is increasing and many investors don't appreciate what they're getting into.

Liquidity risk can be mitigated by only buying ETFs where the underlying asset also enjoys a liquid market. Investors in Vanguard Australian Shares ETF, for example, with $2.4bn under management as of 30 September 2017 are unlikely to face much risk of this sort. The underlying shares it owns offer very liquid markets.

Counterparty risk can be minimised by avoiding synthetic ETFs altogether. Instead of purchasing underlying assets directly, the issuer of a synthetic ETF enters into a swap agreement with a bank to ensure returns track the relevant index. That means the investor is subject to the counterparty's ability and willingness to meet redemptions. As we saw in the global financial crisis, banks aren't always willing counterparties.

Leveraged ETFs use debt to track a multiple of the return of a given index and are also best avoided. Both are examples of how the finance industry takes a good idea and pushes it to dangerous extremes in order to generate more fees, thus undermining the original concept on which it was based.

By avoiding these products, sticking to ETFs that own physical assets in liquid markets, you'll remove a lot of the risks associated with the sector.

Inefficiency out of efficiency

There's also a benefit should the principal criticism of ETFs prove to be true – that they facilitate a wave of dumb money pushing up asset prices whilst making markets more volatile.

As Seth Klarman wrote recently: ‘The inherent irony of the efficient market theory is that the more people believe in it and correspondingly shun active management, the more inefficient the market is likely to become.'

Value investors should welcome more market inefficiency because it's the source of our returns that beat the market over the long term. If ETFs do lead to more mispricings in the future, then that's all good for us.

Note: Members with an interest in ETFs should look out for our inaugural Exchange-Trade Funds Report, which examines the Australian market for ETFs. We will be releasing the report on Thursday (23 November).

Note on the note: This report is now available here.