A dance through the financial aspects of risk

Key Points

- Determine your human and financial capital

- Understand how volatility can create both risks and opportunities

- Combine the psychological and financial aspects

Most of us will have seen our parents trying a bit too hard on the dance floor, and it should have taught us an important lesson: there are some things that are better done when you’re young.

Youth allows the flexibility to get fully into the swing of things; and it makes it a lot easier to pick yourself up if you take a spill.

It’s the same with investing. The composition of your portfolio should reflect your personal tolerance for risk, but it also needs to pay heed to your age and your capacity to absorb shocks.

So the first step in building a portfolio is to work out how much risk you can personally stomach (see The first step in building your portfolio). After that, you need to get financial: how much risk can you tolerate given your stage of life and financial position?

To flesh this idea out a little more fully, you can think of yourself as having two sources of wealth, or income-generating capacity:

-

Human capital, or your ability to generate income from work. The younger you are, the more human capital you’ll have. That’s because you have more time left to work and a greater capacity to improve your human capital through education, career change or promotion.

- Financial capital, which is the more traditional definition of wealth. It’s the dollar amount of assets you own.

Most people starting out in the workforce have the bulk of their wealth tied up in their human capital. At this stage, many people could suffer a 100% loss of their financial capital and replace it within months or a couple of years. So they can afford to invest their financial capital aggressively.

As the years pass, the financial capital tends to grow as the human capital is depleted. Financial capital is generated through home ownership, superannuation and other investments. Human capital is eroded by the passage of time and loss of flexibility.

At some point, due largely to the power of compound interest, the days when a complete loss of financial capital could be easily handled are gone. So as the balance of your wealth tips towards financial capital you should begin to invest it more conservatively.

Keep in mind that this is a gradual transition from a portfolio heavy in assets such as shares and property when young to a portfolio with large allocations to cash, term deposits and bonds as you have less time and ability to work.

That said, it’s not always age-related. Someone in their 60s may have plenty of capacity to earn income through work and a relatively small amount of financial capital.

Another thing to consider is the correlation between your human capital and financial capital. If you work for an investment bank or resources company, for example, and have a load of employee share options, your human capital is ‘invested’ aggressively. So it might make sense to invest your financial capital more conservatively than if you were, say, an accountant or school teacher.

Now, brace yourself for a discussion of volatility. In fact, it might be a good idea to grab a cup of coffee before reading on.

Volatility

Volatility can be defined as the amount and speed at which the price of an asset moves around, or could move around. Cash is the least volatile asset (since a $100 deposit is always priced at $100). Riskier investments such as shares and currencies are more volatile: they can experience large, rapid price swings.

Academics and many members of the finance industry equate volatility directly with risk. We have a more complex view.

In some situations volatility creates risk. In others, it’s the source of great opportunity. It depends on the circumstances.

To a share investor with a margin loan that can be called at any point, volatility creates the potential for the worst possible outcome: being forced to sell at the bottom of the market. In this case, it is clearly a huge risk.

To an investor with a healthy amount of financial ‘dry powder’, volatile share prices create opportunities to buy into attractive situations and wait for the market’s mispricing to correct itself.

So you can see how two investors might greet the same news differently – say, BHP Billiton shares falling from $32 to $20. One is scrambling around trying to find cash to meet a margin call in order to hang onto their current number of shares, the other is in a position to buy more shares at an attractive price.

Apart from margin loans, there are other situations where volatility can be a risk. Steel yourself for a little more technical-sounding language.

Sequence of returns issue

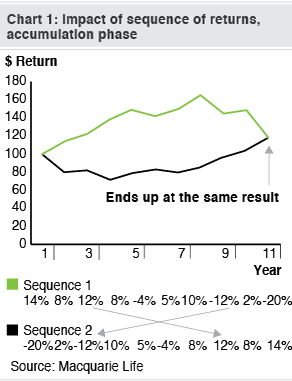

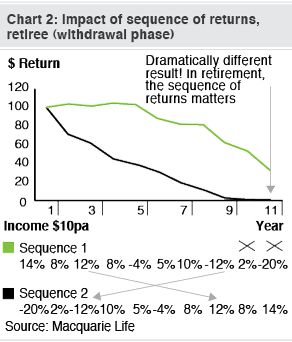

In Can you afford to live to 104? we discussed the ‘sequence of returns’ issue and demonstrated its impact on the returns of investors at different stages of life (refer to Charts 1 and 2).

If you’re not withdrawing capital, then the path an investment takes to its end point has no negative impact on you – downswings in prices are an opportunity, not a risk. In other words, you accept that your portfolio is going to have a few great years, many middling ones and the odd shocker, so you’re not concerned about the order in which they arrive because you’ve got the time to ride them all out.

It’s a different story if you’re living off your investments, though. Or you’re only a few years away from doing so.

In this case, you’re essentially reducing the amount of capital you have invested by making withdrawals. So if you have to sell volatile assets like property or shares on a regular basis, you open up the possibility of having to do so when their prices are irrationally low.

In such a situation, not only are you getting less than fair value for the assets you’re selling, you’re going to miss out on the eventual price recovery. The financial impact could be disastrous.

Investors in ‘withdrawal mode’ need to make sure they have enough invested in stable assets like cash, term deposits and short-term bonds so that they aren’t going to be forced to sell out of more volatile assets during a downturn.

Putting it another way, if you have an impending need for some of your capital, this portion should be invested in stable assets. The definition of ‘impending’ will vary from person to person but we’d say 3-5 years is a decent rule of thumb.

From a financial perspective, the ‘sequence of returns’ issue forces most investors to get more conservative as they become older, so that volatility doesn’t become a risk. There’s some truth to the self-funded retirees who say they don’t have enough time left to be long-term investors.

Another factor dictating that we should become more conservative as we age is our ‘personal balance sheet’.

If you’re young and your financial capital is a small part of your wealth, you have the capacity to invest more aggressively. For some people this will mean a portfolio 100% invested in shares. For others it will mean a balanced portfolio of term deposits, shares and property.

The choice comes down to personal psychology. Many people simply don’t have the stomach to be 100% invested in shares, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

If you’re retired, then you should invest more conservatively than when starting out. For some this will mean being truly conservative, whereas others might simply make the transition from a large allocation to shares to a more balanced portfolio.

Our advice is that it’s best to err on the side of caution, especially if you’re new to self-directed investing. The ‘loss’ of earnings from being too conservative is likely to be a small price to pay compared to the risk of a large capital loss due to be being overly-aggressive – and you’re likely to find it easier to sleep at night.

Think about it this way; there will always be an opportunity down the track to invest for a higher rate of return but you may never be able to replace your financial capital if you lose too much in a risky investment.

Putting the psychological and financial components together

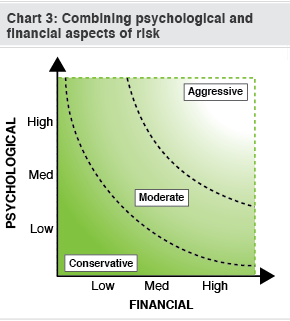

Chart 3 provides a conceptual illustration of how the psychological and financial aspects come together.

Note that only a minority of people should end up truly conservatively or aggressively invested. Most of us will sit somewhere in the 'moderate' zone in between.

Remember that this is a spectrum. Only in the world of externally managed super funds do rigid terms like ‘balanced’ and ‘capital conservative’ matter. The beauty of doing your own thing is that if you can’t decide, you’re free to pick a point half way in between.

Interestingly, it’s not simply a case of saying ‘I’m retired now, so the financial aspects mean I can’t be aggressive’. You should apply a personal weighting to each factor.

If you tend to an ‘all or nothing’ outlook on life you might give the psychological aspects more weight than the financial and invest more aggressively in retirement than the average investor in your financial situation.

For example, some people would prefer to risk ending up on the age pension if it means they have a shot at living an affluent lifestyle. Others can’t stand the idea of living on a meagre government stipend and are determined to live modestly, without the chance of high returns. Neither is right or wrong; it’s simply a personal choice.

There’s no mathematical solution to any of this, for the simple reason that there is no right answer. The financial aspects of risk are principles to be understood, not equations that will produce the perfect portfolio for you. Don’t be fooled by pretty computer programs that suggest otherwise.

Perhaps most importantly, you shouldn’t let one aspect totally rule the other. You might be completely fearful of the sharemarket, currencies and volatility, but if you’re young, it would be a mistake to invest only in cash and term deposits.

Similarly, if you’re psychology says ‘go for it’, but you’re in your late 60s or 70s, then think about easing off the accelerator a little – else you might end up in a heap on the floor.

If you’re young and have an aggressive mindset you might try the investing equivalent of a Gangnam Style horsey dance (if you don’t know what this is then you’d better not try it). If you’re older, or more conservative in nature, a gentle waltz may be in order.