Yield glorious yield, Events, Huawei, Rahaf Alqunun and more

Yield, Glorious Yield

Events, dear investor, events

The Importance of Huawei

The Importance of Rahaf Alqunun

Research and Diversions

Facebook Live

Next Week

Last Week

Yield, Glorious Yield

I was going to make this a later item for my first Overview of the new year, but as I wrote it, I thought: Hell! This needs to go first!

If we lower our eyes from all the geopolitical and monetary uncertainty afflicting the world at the moment, and dealt with at length below, there is some amazing yield value in the Australian market at the moment, and that can cover up a lot of anxiety and doubt.

The forecast yield for 2019 of the ASX 100 right now is 5.34%, which is a little more 3% above the 10-year bond yield. That equity/bond yield spread has never been 3% before! Even at the bottom of the GFC crash it was less than 3%, and it’s usually 1-2%.

And this especially goes for the banks, and especially for NAB. NAB has paid out 99c, fully franked, every six months since 2015, and at the current price that dividend represents a yield of just above 8%. The others are on yields of 6% (CBA), 6.3% (ANZ) and 7.3% (WBC).

The only thing stopping a yield-conscious investor from piling into NAB for a grossed-up yield of 11.4% would be a concern that the dividend will be cut because of the housing bust and the effects of the royal commission.

Well, the dividend probably will be cut, and no one should buy NAB expecting it to stay at $1.98. Consensus broker forecast is for $1.95 over the next few years, hardly a cut at all.

But even if NAB were to cut its dividend to $1.50, taking it back 10 years, that’s still a grossed-up yield of 8.6%.

The other problem, of course, is if you need a cash refund to take full advantage of the franking, in which case – since the ALP will probably win the 2019 election – you need to adjust the grossing-up calculation for your own circumstances.

Two other stocks worth mentioning in this context are IOOF and AMP.

IOOF has been paying 27c every six months for a few years, and since its share price fell by more than half this year as a result of the RC, the stock now yields 10.17%, fully franked, or 14.5% grossed up (assuming you can gross up, of course). AMP yields 9.55%, or 11.2% grossed up, having already cut the dividend from 29c to 20c.

IOOF and AMP are riskier propositions than the banks because, like the banks, they are exposed to the flow of superannuation money out of retail funds and into industry funds, and also the downward pressure on fees, but they don’t have a banking business to fall back on. That would change, and bank risks would rise, if the housing decline became disorderly and led to a lot of defaults and a rise in unemployment, but for the moment IOOF and AMP deserve to be on higher yields than the banks.

The banks’ PE ratios aren’t challenging at the moment – an average of 10.7 times – so you would not be overpaying. By the way the cheapest bank on a PE basis is CYBG plc, the old Clydesdale and Yorkshire banks demerged by NAB, selling on a PE of 6.8, although it’s definitely not a yield play – yield is 1.65%, unfranked.

The other high-yielder worth mentioning as 2019 gets underway is Alumina (10.4% fully franked). The aluminium price is down about 20% in 2018, so less risk with this stock now. Most analysts are forecasting a recovery in metal prices this year, although that depends on what happens with the matters discussed below.

Events, dear investor, events

As Harold MacMillan is meant to have said when asked by a young journalist, or possibly John F Kennedy, what can blow politics off course: “Events, dear boy, events.”

Same with markets, although as with politics the events need context – some sort of underlying pressure to raise the general sensitivity.

With politics, it’s public opinion, usually expressed in polling. In the case of markets, it’s valuation.

As 2018 began, the US market sat on a slightly stretchy forward PE of 18.5 and the tech stocks were on stratospheric valuations. The Australian market was on 16 times, above average but far from stupid; in Europe, something similar. They have all since de-rated significantly in two corrections that made 2018 a most unhappy year for investors.

.png)

In looking ahead to 2019 and trying to work out what might happen from here, we need to understand what happened to cause the de-rating. Were there events? Or was it simply a Minsky Moment, that is a sudden drop in asset values caused by nothing more than complacency?

In fact, there are four events in the second half of 2018 that help explain what happened and provide pointers to the future.

The first two happened on October 3 and October 4, coinciding exactly with the start of the brutal 16% US market correction that bottomed on Christmas Eve. They were:

- Fed chairman Jerome Powell was interviewed onstage at The Atlantic Festival and about halfway through the interview made the following off the cuff remark: “Interest rates are still accommodative, but we're gradually moving to a place where they will be neutral. We may go past neutral, but we're a long way from neutral at this point, probably."

- The next day, US Vice President Mike Pence gave a speech at the Hudson Institute about China which was, to say the least, tough, including the following statements: “the Communist Party has set its sights on controlling 90% of the world’s most advanced industries, including robotics, biotechnology, and artificial intelligence. … Beijing now requires many American businesses to hand over their trade secrets as the cost of doing business in China. … Worst of all, Chinese security agencies have masterminded the wholesale theft of American technology – including cutting-edge military blueprints.”

After that, the S&P 500 immediately fell 10% over the following three weeks before there was what you might call jerky stability for a couple of months (big ups and downs while going sideways). The ASX 200 fell 8.5% after October 4, having already fallen in September.

Then, in early December came the second round of the correction, in two phases leading up to Christmas, starting with…

- The arrest of the CFO of Huawei, Meng Wanzhou, on December 6, and then…

- The Fed meeting and statement on December 19, after which the Fed funds rate was lifted 25 basis points and the statement maintained the “hawkish” line from Powell’s October statement.

Obviously numbers 2. and 3. are related – one event really - as are 1. and 4.

Most commentary about relations between US and China refer to it as a trade war, but those events 2. and 3. suggested that it runs far deeper than that. Events 1. and 4. forced markets to adjust their thinking about how many US rates hikes were coming.

There were a few other events weighing on markets, such as Donald Trump’s repeated attacks on the Fed and Jerome Powell. These got quite serious on October 10 at a rally, where he said “they’re so tight. I think the Fed has gone crazy.” A fortnight later he said “I’m not going to fire him”, which of course made everyone think he might. And in November he said: “I think the Fed right now is a much bigger problem than China.” And so on, on Twitter, right up until Christmas.

Also Brexit was bubbling away and so were Italy’s budgetary problems, and the oil price was collapsing – good for inflation and interest rates, bad for energy stocks. And then there’s been Apple’s 40% crash, as the market reassesses the prospects for iPhone sales.

But last year’s negative returns were mainly about Fed tightening and China/US trade, or more broadly the end of the great central bank liquidity support (for the 4th time) and the “War of Civilisations” between the US and China.

.jpg)

And after seeing the market’s reaction, the Fed and the White House are now busily trying to hose down all the fears.

Jerome Powell started up with the hose on January 4. He was on a panel with his predecessors, Janet Yellen and Ben Bernanke, and said this: “I think the markets are pricing in downside risks, is what I think they’re doing. And I think they’re obviously well ahead of the data, particularly if you look at this morning’s labour market and other data. Market are expressing concerns about global growth in particular, I think that’s becoming the main focus, and trade negotiations which are related to that, and I’ll just say that we’re listening carefully to that, we’re listening sensitively to the message that markets are sending, and we’re going to be taking those downside risks into account as we make policy going forward.”

“Aha! Rate hike pause!” said the markets, and the S&P 500 rallied 3.4% that day.

Since then there has been a succession of Fed speeches basically giving the same message, culminating in the minutes from the December 18-19 meeting published on Wednesday this week, with the following paragraph: “…participants expressed that recent developments, including the volatility in financial markets and the increased concerns about global growth, made the appropriate extent and timing of future policy firming less clear than earlier. Against this backdrop, many participants expressed the view that, especially in an environment of muted inflation pressures, the Committee could afford to be patient about further policy firming.”

Pause confirmed, sort of.

Meanwhile, on December 30, Trump tweeted: “Just had a long and very good call with President Xi of China. Deal is moving along very well. If made, it will be very comprehensive, covering all subjects, areas and points of dispute. Big progress being made!”

Since then there has been a succession of leaks and statements about how well the new round of talks is going. Then on Wednesday the US Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer issued a statement about this week’s US trade delegation to China, which was: “as part of the agreement reached by President Donald J. Trump and President Xi Jinping in Buenos Aires to engage in 90 days of negotiations with a view to achieving needed structural changes in China with respect to forced technology transfer, intellectual property protection, non-tariff barriers, cyber intrusions and cyber theft of trade secrets for commercial purposes, services, and agriculture.

“The talks also focused on China’s pledge to purchase a substantial amount of agricultural, energy, manufactured goods, and other products and services from the United States. The United States officials conveyed President Trump’s commitment to addressing our persistent trade deficit and to resolving structural issues in order to improve trade between our countries.”

So here’s the key question or investors as 2019 begins: is everything OK now? Are all the concerns about Fed tightening and trade war over? Has the bull market resumed?

Certainly the 10% S&P 500 rally since Christmas Eve (6.3% on the ASX200) suggests that the market wants to believe that. I want to believe it too.

But can I? Well, almost … I’m trying to. After all, bear markets usually last about a year or so and, globally, this one started last Australia Day. That was the MSCI peak, although both the S&P 500 and the ASX 200 made new highs in August/September between the first and second 2018 corrections.

The positives are as follows:

The equity risk premium (the difference between equity yield and the bond rate) is back at levels that usually signal a bottom:

.png)

A record number of asset classes went backwards in 2018…

.png)

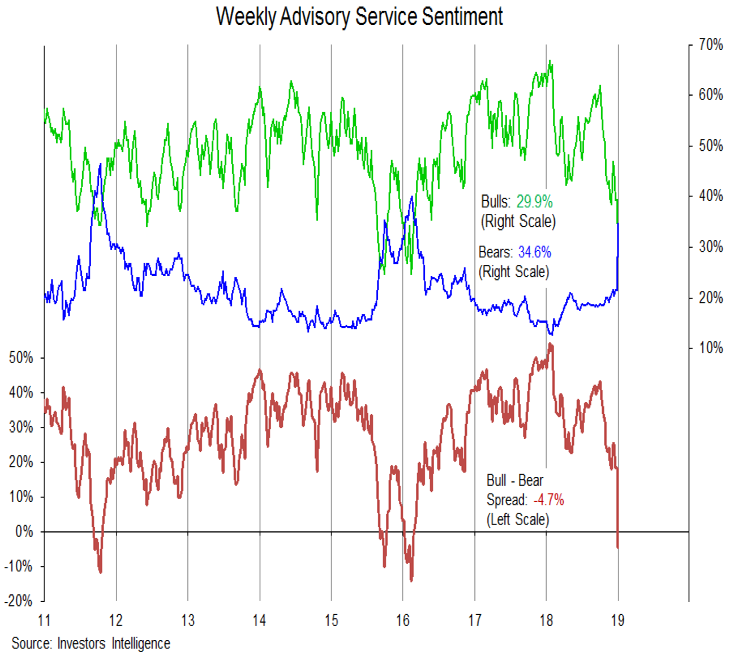

And sentiment is almost universally bearish, which is always a good sign.

But have the two big themes that caused the bear market – Fed tightening and trade wars – really changed? Maybe, but I doubt it.

I’ll explain my views on what’s behind the China/US situation in the next item, but as for the Fed and central banks generally, I doubt that anything fundamental has changed in the last few weeks, which is both bad and good.

First, a major turning point has occurred: major central banks (except Australia) are now trying to normalise post-GFC monetary policy. Money printing has ended and the Fed, at least, has been hiking rates for three years. And despite the recent soft-talking, the Fed won’t seriously pause with economic data running the way it is: the fact is the US economy is doing fine and payrolls in particular are booming. As Powell said on October 3, the Fed thinks the Phillips Curve (the relationship between employment and inflation) is – like the parrot in the Monty Python - not dead, it’s just resting. (“Beautiful plumage.”)

Second, it’s clear from statements over the past couple of weeks that the Fed will not hesitate to open the liquidity spigots again if things head south. In other words the “Fed put” is still active.

There’s a very important reason for this:

.png)

The relentless rise in global debt has continued after the GFC. I think this means that central banks now see it as part of their responsibility to control asset prices, and specifically to prevent generalised insolvency.

It’s the same as when a company takes on too much debt: a liquidity crisis can quickly turn into a solvency crisis, so a bank that doesn’t want to send the business to the wall and end up holding the assets, will maintain the overdraft and working capital so the company doesn’t accidentally run out of cash.

In a sense, after the GFC central banks provided the world with working capital (liquidity) so the value of assets could be maintained and the world didn’t become insolvent (debt greater than assets). Asset values are not explicit in any central bank mandate, but it’s there - maintaining employment, which is in the mandates, depends on it.

That strategy has been wildly successful apart from two bear markets – 2014-15 and 2018. The debt is still there, in fact it’s now 10% higher as a percentage of GDP than it was in 2014 and 20% than in 2009.

As for whether the Christmas Eve low was the bottom of the cycle, I don’t know. It might have been, but the problem is global growth is now weakening significantly and seems to some way off a bottom. In fact, with the even greater decline in money supply (M1), some people are saying that a global recession is now assured.

.jpg)

And global earnings downgrades are the highest they have been for years:

.jpg)

Still I do think the 2018 (and possibly 2019) equity bear market is cyclical, within a secular bull market, not the start of a secular (ie long) bear market. On that score, I agree with Morgan Stanley’s global strategist, Mike Wilson, who produced this excellent chart this week:

.png)

At the risk of over-simplifying, events cause corrections while bear markets require recessions and/or valuation blow-outs, as in 2000.

Obviously all bets are off if there really is a global recession. The New York Fed’s recession probability model for the US is above 25%, so it’s elevated. The only time a recession has followed when it’s at that level was in 1960, so not impossible, but unlikely. It needs to be higher than that … although as the last three recession showed, not all that much higher – 30-40% would do it apparently.

.png)

Anyway, I reckon the Fed would be cutting and printing money well before that because the precedent has been set and they have been showing in word and deed that that is what they would do.

As Chris Weston wrote in a note the other day: “The market didn’t like what it originally heard from Powell, and sensed that he was happy to be a high volatility Fed chair. But their rebuttal was aggressive, ultimately, pushing the Fed to a point where it had no choice but to respond, and even if the world's economy proves to be not as bad as what was being priced, when financial conditions tighten radically, the Fed will respond.”

Where I diverge from Chris is his headline, which said: “The market owns the Fed”. I think it should be the other way around: “The Fed owns the market”.

The Importance of Huawei

Empires are usually based on the control of transport.

For Rome it was roads, as in “all roads lead to Rome”. For the British empire it was maritime supremacy and control of the sea lanes. For America it started as control of the sea, specifically the seaborne oil trade, then the air, symbolised by the Boeing 747, and more recently American hegemony has been led by Silicon Valley, and control of the internet – that is, transport of data.

The world’s most powerful corporations these days are US technology giants – the FAANGs. The internet itself is managed from California, the routers made by Cisco and other American firms.

It’s clear that although the US and China are still spending colossal sums on maintaining vast militaries, the theatre of their rivalry is technology.

That’s what VOP Mike Pence was on about in his seminal speech on October 4 and that’s what the trade war is all about – trying to force China to stop its hacking and technology transfer demands and more fundamentally encourage US companies to shift their supply chains away from China.

China’s “belt and road” infrastructure plan is as much about telecommunications as roads, with China’s money building fibre networks throughout the region and subsidising equipment bought from its own suppliers, led by Huawei.

So to some extent, Huawei is the East India Company or the Boeing of our age, spearheading China’s push for dominance of telecommunications. America, supported by its allies, is resisting it – banning Huawei as a supplier and, a month ago, arresting its CFO.

This is going to play out over years and perhaps decades, not weeks, so the fact that the current trade talks between the US and China are getting nowhere is hardly surprising. There may be minor breakthroughs for short-term political reasons on both sides, but no investor should expect a big lasting “truce” between the two countries. The negative pressure and occasional panicky sell-offs from the trade war are likely to be part of our lives for all of 2019 and beyond, I suspect.

An interesting question is whether the Huawei situation is America’s Suez Crisis.

That was Britain’s last attempt to assert its control of the sea lanes. In 1956, Israel, and then Britain and France, invaded Egypt to regain control of the Suez Canal after President Nasser nationalised it. It later emerged that the three countries had cooked up the plan together

It turned into a humiliation for Britain after US President Dwight D Eisenhower threatened to destroy the value of its currency by selling sterling bonds if it didn’t withdraw. The crisis formally brought to a close Britain’s time as a great power.

(Discussion for the UK to join the European Union and regain some relevance began 13 years later and concluded with its EU membership in 1973. In that context, Brexit would the tombstone on the British Empire).

Anyway, there may be some kind of “Suez Crisis” for the US as it tries to maintain its technology hegemony against China, but I doubt that Meng Wanzhou’s arrest will be it.

Mind you, things are definitely heating up. Last night Poland arrested a Chinese Huawei employee, along with a former Polish security services person, on charges of spying.

The Importance of Rahaf Alqunun

You’ve probably seen this story – the 18-year-old Saudi woman who was spirited out of the country to escape her murderous family but was detained in Bangkok on her way to seeking asylum in Australia.

The reason for mentioning it here is that it’s another step on Saudi Arabia’s loss of prestige and bargaining power – another very public display of how out of step with the rest of the world this country has become.

The first big step in this process in 2018 was the murder of Jamal Khashoggi in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, the reaction to which seems to have caught Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman by surprise.

Here’s the front page of Thurday’s Washington Post:

.jpg)

None of it would matter if Saudi Arabia wasn’t the world’s largest producer of oil and if the collapse of the oil price in the second half of 2018 had not sent the country, and the rest of OPEC, back to the brink of financial collapse. But it is, and it has.

This week Saudi Arabia successfully sold more than US$7 billion in bonds to shore up its budget, so global investors, at least, are still on board, willing to chuck money at the Saudis.

Look, I’m not suggesting that the case of Rahaf Alqunun is as big a deal as that of Jamal Khashoggi, or even that either of them is some kind of tipping point for Saudi Arabia, but I think that its new status as a pariah state is likely to become more of an issue as 2019 goes on, and it will be a growing problem for the United States, and the oil market.

Research and Diversions

(It’s a big R&D this week – a collection of stuff I’ve been reading on holidays)

Research

Residential property declines of the past – the lessons of history.

Wall Street has priced in the Trumpcession.

Barry Dawes on what’s in store for 2019 (a taste: “Equity volatility to continue but global bull markets intact”).

Here’s another view: “The rise of worldwide populism, an insular tech world unable to correct its blunders, a devastated journalistic landscape that gives an open-field to the social mob, there are little reasons for optimism this year.”

Prospects for 2019 – a true or false game on video with Matthew Kidman and a group of other fund managers, via Livewire Markets. Among other things: “AMP is the widow’s trade…”

Pete Wargent: housing credit has no pulse.

GDP is no longer an accurate measure of economic progress. Here's why

Can any country possibly be more exceptional than America, which was founded with neither a king nor a pope? No, of course not! Yet, today, not only is America most religious among the developed countries, she also seems to be yearning for a king, if not a living God (Is Donald Trump a God?). Why is that? It's 'tyranny of the majority' (aka "democracy").

Marvellous essay: the digital revolution has turned into something else. ““We assume that a search engine company builds a model of human knowledge and allows us to query that model, or that some other company builds a model of road traffic and allows us to access that model. This fits our preconception that an army of programmers is still in control somewhere, but it is no longer the way the world works. The search engine is no longer a model of human knowledge, it is human knowledge.”

Since Apple admitted that iPhone sales were weaker than expected, the focus has been on what went wrong in China. We should be asking: what went wrong everywhere else?

The real crisis on America’s southern border is not a flood of criminals and terrorists (they come via airports), but an administrative-processing problem. “Immigration policy has always given rise to pitched political battles, on the left and on the right, but this is the first time in modern memory that an American President has openly and deliberately stoked these divisions for the sake of partisan theatre.”

When sentiment turns this gloomy, if bad news does not follow, a sharp rebound in stock prices can come in response to any of a sizable number of possible positive events. And right now, the list of potential positive catalysts is long.

Is the hype about CBD, or cannabidiol, real? Err, maybe, maybe not.

John Mauldin: I expect to spend this year Living Dangerously. Yes, I’m thinking of the 1982 film starring a very youthful Mel Gibson and Sigourney Weaver, based on an earlier Christopher Koch novel. It has an Asian setting and features corrupt politics, neophyte journalists, international intrigue plus a gender-bending Chinese dwarf. If you aren’t sure how all those fit together, then welcome to 2019. We are all stuck in this craziness and can only make the best of it.

A reading list for unorthodox economists.

Where is the next great boom of innovation going to come from, when even the strongest brands and products might not be sure things anymore?

Innovation isn’t always good. This is a video about how financial innovation helped cause the 2008 crisis.

How the economic machine works – a video by Ray Dalio.

A complete guide to all 17 (known) Trump/Russia investigations.

Is something wrong with Donald Trump – neurologically? “After more than a year of talking to doctors and researchers about whether and how the cognitive sciences could offer a lens to explain Trump’s behavior, I’ve come to believe there should be a role for professional evaluation beyond speculating from afar.”

How Mark Burnett (producer of The Apprentice) resurrected Trump as an icon of American success.

Nomura: "It Is Increasingly Obvious That Powell Believes The Fed Has Engendered Outright Asset Bubbles".

How innovation happens. This study tracks the emergence of portable digital music players, from the adoption of the MP3 standard for compressing audio signals in 1992 to the emergence of Apple’s iPod as the market leader in 2004. The inventors of the MP3 algorithm made millions; but Apple made billions. “Apple realised that the metric most important to customers was ease-of-use.

.jpg)

As many countries have learned the hard way, Chinese development finance often delivers a corruption-filled sugar high to the economy, followed by a nasty financial (and sometimes political) hangover.

Paul Krugman: coverage of Trump’s 2017 hasn’t been negative enough. The story you mostly read runs something like this: The tax cut has caused corporations to bring some money home, but they’ve used it for stock buybacks rather than to raise wages, and the boost to growth has been modest. The reality: No money has, in fact, been brought home, and the tax cut has probably reduced national income. Indeed, at least 90 percent of Americans will end up poorer thanks to that cut.

A (long) review of Yanis Varoufakis’s book, Adults In The Room: My Battle With Europe’s Deep Establishment: “the Greek government is committed to sending 3.5 percent of national income abroad as tribute to its creditors each year, for the indefinite future. The battle by Varoufakis and his Syriza comrades against this intolerable state of affairs is, even in defeat, a rare spot of genuine heroism in today’s discouraging political landscape.”

Don’t worry about super smart AI eliminating all the jobs. That’s just a distraction from the problems even relatively dumb computers are causing.

Peter Martin: My magnificent seven. Seven really bright ideas (and one as old as time itself) from 2018.

New research by economist Utsa Patnaik - just published by Columbia University Press - calculates that Britain stole nearly $45 trillion from India during the period 1765 to 1938.

The invention of capitalism and liberalism in Western Europe should be traced to one surprising source: the medieval Catholic Church.

A discussion with the pioneer of behavioural economics, Daniel Kahneman. He warns against trusting in intuition, save for top athletes and chess players. “The problem with intuition is that it forms very quickly, so that you need to have special procedures in place to control it except in those rare cases where you have intuitive expertise.

The biggest problem in the oil market right now is the mercurial, unpredictable White House (according to the oil industry).

Diversions

I’m pleased to announce Kohler’s Numi 2.0 Intelligent Toilet, which will give the user a “fully-immersive experience” thanks to many “lighting and audio enhancements”. They’ll be able to set the mood, using voice commands to cue up music and customize the lighting, all while Kohler’s PureWarmth toilet seat toasts their behind to their preferred temperature. Finally, the technological revolution has come to pooping.

“52 things I learned in 2018”. For example: Tyrannosaurus Rex is closer in time to humans than to Stegosaurus. You are 44% more likely to die if you have surgery on a Friday. After people wash their hands, their views on immigration reform move politically to the left.

Another what I learned in 2018. Interesting throughout. Topics include Moore’s Law; opera; Chinese industry; moonshots; ultimate fighting; and Avalon, a game of logic and lies.

Going into 2019, it is in businesses’ self-interest and for the greater good that we shape this Fourth Industrial Revolution more actively. Left unmanaged, technologies will shape us, and in the age of A.I. and malicious “lone wolves,” the risk of harm is greater than ever. To counteract it, I propose four points of action.

I’m counting this as a diversion rather than research, but it’s kind of weirdly serious: a mash-up of Donald Trump saying he knows more about … (you name it) than anyone.

Return of the neocons: A new configuration of right-wing foreign policy is coming into view.

A funny thing happened on the way to developing quantum computing: physicists found evidence of a deep connection between quantum error correction and the nature of space, time and gravity. Space and time themselves could be quantum errors. Mind-bending stuff!

Beautifully produced interview with a hermit named Billy, the only inhabitant of a remote and abandoned mining town in Colorado. He moved there 40 years ago wanting to be alone. He’s still there.

A millennial writes about millennial burnout: “the more work we do, the more efficient we’ve proven ourselves to be, the worse our jobs become: lower pay, worse benefits, less job security. Our efficiency hasn’t bucked wage stagnation; our steadfastness hasn’t made us more valuable. If anything, our commitment to work, no matter how exploitative, has simply encouraged and facilitated our exploitation. We put up with companies treating us poorly because we don’t see another option. We don’t quit. We internalize that we’re not striving hard enough. And we get a second gig.”

I used to think that paper books would be quickly replaced by e-books. I was wrong – it hasn’t happened, and to be honest doesn’t really look like happening. The digital revolution has happened, and the physical book has survived; the market is largely intact; the ebook is bedding down an innovation roughly on the scale of the paperback, not on the scale of moveable type. But there has been a revolution: “Funding, printing, fulfillment, community-building — everything leading up to and supporting a book has shifted meaningfully, even if the containers haven’t.”

The freaky foods of science fiction.

"What looks like the death of truth is actually the death of consensus, and a broader transition to a world of dissensus." Dissensus? Is that actually a word? I don’t think so. Still, it’s an interesting piece.

Protein mania: the rich world’s new diet obsession. “When we seek out extra protein to sprinkle over our diets, most of us in rich countries are fixating on “a problem that doesn’t exist”.”

Fascinating piece about Trump’s epic battle to save his Florida mansion, Mar-a-Lago in the 1990s. “Back in the mid-90s, Trump was a nearly bankrupt grifter who fell in love—with a beachfront resort. In order to save Mar-a-Lago, he took on Palm Beach, went to war with the National Enquirer, and race-baited. It was the fight of his life.”

The post-Presidential life of Mikhail Gorbachev. Yes, he is still alive, though you might be forgiven for imagining otherwise. For a decade or so after the fall of the Soviet Union Gorbachev could earn huge sums from American speaking tours; then it was TV commercials; now not even that. The loss of greatness weighs heavily on him.

The importance of staring out the window. “We don’t go around saying: ‘I had a great day: the high point was staring out of the window’. But maybe in a better society, that’s just the sort of thing people would say to one another.”

How do you make a sex scene in a movie sexy? (And keep the actors safe?) You employ “intimacy co-ordinators”, that’s how. Five of them explain their craft.

Nick Cave’s response to a fan about the death of his son is just extraordinary.

The world is on a collision course with itself. “The internet is designed to harbour isolated, extremist ideologies. What happens when they meet?”

Single-malt Scotch whiskies are produced by 109 distilleries in Scotland. The layman may wonder what are the major types of single malts that can be recognized, and what are their chief characteristics and best representatives, whether there is a geographical component in that classification and whether the various categories of characteristics lead to the same classification. This paper provides an answer to these questions, applying an array of statistical methods to a database derived from a connoisseur's description of these liquors.

This a fantastic interview I heard this week on the Religion and Ethics Report on Radio National – Andrew West interviewing Jordan Peterson. But I see that it was first broadcast in April 2018. Oh well, I thought it was fascinating – nothing to do with investing of course, but worth a listen if you have time (half an hour).

All 213 Beatles songs, ranked from worst to best.

The most interesting chef in the world. Profile of Argentinian chef Francis Mallman, “shaman of smoke”, who runs nine restaurants, mostly in South America, but prefers to live off the grid on a Patagonian island. He cooks in an open-air shed made of logs. There is steak at least once a day. Lunch might include a whole lamb, with kidneys served separately, a loose mountain of roast tomatoes and blackened bread, and pancakes with dulche de leche.

A (relatively) brief military history of World War One, efficiently and effectively written. The war killed 8.5 million soldiers and 12 million civilians. “You might think Europe and its 40 million finally dead or wounded were dragged into the muck by a series of insults and bumbling miscommunications. Not so, according to many participants. “The struggle of the year 1914 was not forced on the masses—no, by the living God—it was desired by the whole people.”

Albert-László Barabási claims to have arrived at a theory of success by feeding databases of human achievements into machine-learning algorithms. The elements of his theory, in brief: Performance drives success. But when performance can’t be measured, networks drive success. Performance is bounded, but success is unbounded.

Happy Birthday Paul Kelly, 63 tomorrow. Thank God for Paul Kelly. He wrote a lot of wonderful songs, but this one is his best: “How To Make Gravy”.

.png)

.jpg)

In response to Fraser Anning charging taxpayers to attend the Nazi rally in Melbourne:

.jpg)

Meanwhile in Portugal:

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Facebook Live

#AskAlan on our Facebook group returns next week. this week (or if you don’t have access to Facebook) you can catch up here.

If you’re not on Facebook and would like to #AskAlan a question, please email it to hello@theconstantinvestor.com then keep an eye out for the Facebook Live video in next week’s Overview.

Last Week

By Shane Oliver, Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist, AMP Capital.

Investment markets and key developments over the past week

- Since our last weekly update three weeks ago investment markets have been on a bit of a roller coaster ride, with Santa missing Christmas for markets but arriving the day after. Global shares led by the US continued to plunge into Christmas as the US saw the start of a partial government shutdown taking the decline in the US share market to 19.8% from its September high. But since Christmas share markets have rebounded, credit spreads have narrowed and the $US has fallen as investors have become a bit less nervous about the outlook helped by a more dovish Fed, signs of progress on the US/China trade issue and maybe a bit of Christmas/New Year cheer. The past week has seen shares continue to rally, government bond yields decline, oil and the iron ore price move higher and the $US fall which has seen the $A push higher.

- While the recent rebound in share markets has come on good breadth (ie strong participation across sectors and stocks) and is confirmed by other markets like credit and a rally in “risk on” currencies it’s too early to say that we have seen the lows. Global growth indicators look like they could still slow further in the short term and there are a bunch of issues coming up that could trip up markets including US December quarter profit results, US/China trade negotiations, the US government shutdown, the need to raise the US debt ceiling, the Mueller inquiry, Brexit uncertainties, the Australian election, etc. So markets could easily have a retest of the December low or even make new lows in the next few months.

- However, our view remains that the falls in share markets – amounting to 18% for global shares, 20% for US shares and 14% for Australian shares from their highs last year to their December lows – and any further falls to come in the next few months are unlikely to be the start of a deep (“grizzly”) bear market like we saw in the GFC and that by year end share markets will be higher. The main reason is that we don’t see a US, global or Australian recession anytime soon as monetary conditions are not tight enough and we haven’t seen the sort of excesses in terms of debt, investment or inflation that normally precede recessions. In relation to this the following points are also worth noting:

- First, the US share market has seen six significant share market falls ranging from 14% to 34% since 1984 that have not been associated with recession & saw strong subsequent rebounds.

- Second, each of these have seen some sort of policy response to help end them and on this front recent indications from the Fed including Fed Chair Powell about being patient, flexible and using all tools to keep the expansion on track are consistent with it pausing its interest rate hikes this year, Chinese officials are continuing to signal more policy stimulus including cutting banks’ required reserve ratios and we expect the ECB to provide more cheap bank funding.

- Third, negotiations between the US and China on trade look to be proceeding well although they are still at early stage and won’t go in a straight line. China in particular announced more tariff cuts and a commitment to treat foreign firms equally.

- Fourth, President Trump wants to get re-elected in 2020 so he is motivated to do whatever he can to avoid a protracted bear market and recession and this includes seeking to resolve the trade dispute and ending the partial government shutdown before it causes too much damage.

- Fifth, while the oil price has bounced off its lows it’s still down 30% from its high taking pressure off inflation and providing a boost to spending power.

- Finally, a year ago investors were feeling upbeat about 2018 on the back of US tax cuts, stronger synchronised global growth and strong profits and yet 2018 didn’t turn out well. So, it may be a good sign for 2019 from a contrarian perspective that there is now so much uncertainty and caution around.

Major global economic events and implications

- US data was mixed over the last three weeks. Consumer confidence, the ISM business conditions indexes, small business optimism and job openings all fell. And on the strong side, jobs growth in December was much stronger than expected and wages growth continued to edge higher. This mixed data is consistent with the Fed’s more cautious approach.

- Eurozone unemployment fell to 7.9% in November which is well down from its 2013 high of around 12%. The trouble is that economic confidence slid for the 12th month in a row in December suggesting that growth momentum may be continuing to slow. Which with core inflation stuck at just 1% in December will keep the ECB dovish.

- Japan saw stronger wages growth, but still not by enough to move the Bank of Japan.

- Chinese data has been soft. Services conditions PMIs rose slightly in December but manufacturing PMIs fell and this is of greater significance globally. Reflecting the slowdown in China Apple cut its outlook citing slower demand from China. Falling consumer and producer price inflation in China for December is also consistent with slower growth. Reflecting China’s growth slowdown the PBOC cut banks’ required reserve ratio again freeing up more funds for lending.

Australian economic events and implications

- Australian economic data over the last three weeks has been soft with weak housing credit, sharp falls in home prices in December, another plunge in residential building approvals pointing to falling dwelling investment (see chart), continuing weakness in car sales, a loss of momentum in job ads and vacancies and falls in business conditions PMIs for December. Retail sales growth was good in November but is likely to slow as home prices continue to fall. Anecdotal evidence points to a soft December and reports of slowing avocado sales – less demand for smashed avocado on rye? – may be telling us something. Income tax cuts will help support consumer spending, but won’t be enough so we remain of the view that the RBA will cut the cash rate to 1% this year.

.png)

Another blowout in bank funding costs is adding to the pressure for an RBA rate cut. The gap between the 3-month bank bill rate and the expected RBA cash rate has blown out again to around 0.57% compared to a norm of around 0.23%. As a result, some banks have started raising their variable mortgage rates again. This is bad news for households seeing falling house prices. The best way to offset this is for the RBA to cut the cash rate as it drives around 65% of bank funding.

.png)

What to watch over the next week?

- In the US, expect to see a solid gain in December retail sales (Wednesday), a slight rise in homebuilder conditions (also Wednesday) but a fall in housing starts (Thursday) and a modest rise in industrial production (Friday). January manufacturing conditions surveys for the New York and Philadelphia regions should show a slight rise and will be watched closely given their plunge last month. US December quarter earnings will start to flow with an 18% yoy rise expected, although the focus will be on corporate guidance with profit growth likely to slow to 5% this year as the corporate tax cut drops out.

- In the UK, PM May’s Brexit deal faces likely defeat in a parliamentary vote on Tuesday. Even though the UK parliament will force May to come up with a Plan B there is no majority supporting in parliament for any alternative. So the Brexit comedy will continue. A no deal Brexit could knock the UK into recession and maybe knock 0.5% of Eurozone growth.

- Chinese trade data for December (Monday) is likely to show subdued growth in exports and imports.

- In Australia, expect declines in both consumer confidence (Wednesday) and housing finance (Thursday).

Outlook for investment markets

- With uncertainty likely to remain high around the Fed, US politics, trade and growth, volatility is likely to remain high in 2019 but ultimately reasonable global growth and still easy global monetary policy should drive better overall returns than in 2018 as investors realise that recession is not imminent:

- Global shares could still make new lows early in 2019 (much as occurred in 2016) and volatility is likely to remain high but valuations are now improved and reasonable growth and profits should decent gains through 2019 helped by more policy stimulus in China and Europe and the Fed having a pause.

- Emerging markets are likely to outperform if the $US is more constrained as we expect.

- Australian shares are likely to do okay but with returns constrained to around 8% with moderate earnings growth.

- Low yields are likely to see low returns from bonds, but they continue to provide an excellent portfolio diversifier.

- Unlisted commercial property and infrastructure are likely to see a slowing in returns over the year ahead. This is likely to be particularly the case for Australian retail property.

- National capital city house prices are expected to fall another 5% or so this year led again by 10% or so price falls in Sydney and Melbourne on the back of tight credit, rising supply, reduced foreign demand and tax changes under a Labor Government impact. The risk is on the downside

- Cash and bank deposits are likely to provide poor returns as the RBA cuts the official cash rate to 1% by end 2019.

- Beyond any further near-term bounce as the Fed moves towards a pause on rate hikes, the $A is likely to fall into the $US0.60s as the gap between the RBA’s cash rate and the US Fed Funds rate will still likely push further into negative territory as the RBA moves to cut rates. Being short the $A remains a good hedge against things going wrong globally.