Who's afraid of a falling yuan?

Summary: There are two views on China's recent devaluation of its currency: That the government is trying to buttress a weakening economy, or that it's just another step in financial market liberalisation. It's worth remembering the currency has strengthened considerably over the last decade and is now likely headed lower still. |

Key take-out: To the extent that a weaker yuan lifts Chinese growth, that is good news for Australia. But much depends on how Japan and the US react, and whether these countries respond by printing more money or leaving rates lower for longer. |

Key beneficiaries: General investors. Category: Economy. |

What's China up to? There are two dominant views. One is that the government is trying to devalue the currency to buttress a weakening economy. Taking that view further, some see it as yet another sign that the government is increasingly desperate to stave off a downturn.

The other is that it's just another step in financial market liberalisation. So if you take the Chinese government at its word, the recent renminbi (or yuan) devaluation is nothing to be concerned about. The fulfilment of a promise to allow the yuan to trade within a wider band and so simply another step in the adoption of a fully floating currency. The People's Bank of China suggests that the intention of the move was to eliminate distortions in how the currency was being quoted, so as to bring the exchange rate in line with market forces.

From their point of view, all of the confusion on the Chinese economy, the timing of the first US Fed rate hike and events in Europe and Japan – not to forget commodities – was playing havoc with how the renminbi was quoted. So on one hand, China's large trade surplus was pulling the currency higher, yet concerns that the Chinese economy was slowing or threatened by some sort of debt bubble were pulling in the other direction. The authorities felt that by changing the way the currency quote was determined, there would be less intra-day volatility.

At the outset, both are reasonable propositions. The problem is the market can't know with any certainty what exactly it is that the Chinese are trying to achieve.

In trying to make some sense of how things might play out, it's worth bearing a few things in mind.

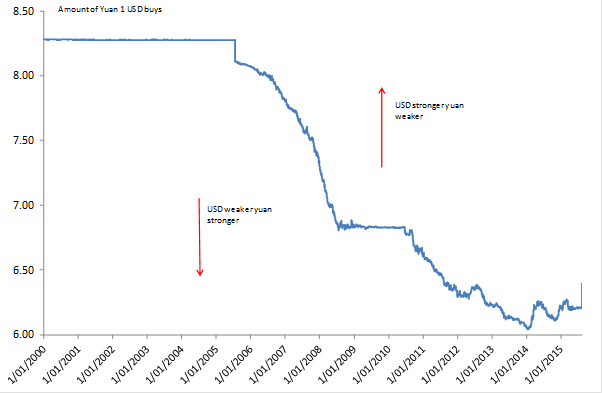

First, the yuan has strengthened considerably over the last decade – about 23 per cent. From its peak strength position, the yuan has only lost 5 per cent of that gain. Being reasonable about it, that doesn't really seem to matter too much.

Chart 1: Renminbi has strengthened considerably over time

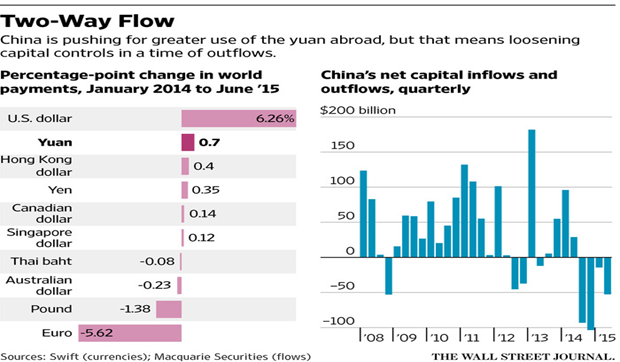

Second, take a look at chart 2 below. With all the concern about the health of the Chinese economy, money has actually been flowing out of China at a rate of knots. Hundreds of billions since 2014. That outflow actually puts downward pressure on the renminbi. Indeed the Chinese had to intervene in the market by selling off some foreign exchange reserves in order to support the yuan. Presumably if they wanted to see some sort of sharp devaluation, then all they had to do was not sell their reserves.

Chart 2: Money is flowing out of China

That being the case, maybe the Chinese are merely marking to market as it were – if just belatedly. Adjusting the fix in order to reflect the market reality that money is flowing out and putting downward pressure on the exchange rate. With a softer economy and slowing exports, the Chinese authorities may have simply decided that there was no point in selling off reserves to defend a currency that was too strong. This seems the most likely explanation for their actions in my view.

In that sense all the fear and loathing over China's devaluation would appear misplaced. Remember, if the government was terrified by a downturn they wouldn't be mucking around with the exchange rate as such. They would lift government spending – public debt and budget deficits are very low. That's their main economic tool after all, not exchange rate or even interest rate management.

What's the end game? On either of the above views, the currency is likely headed lower still. The Chinese are adamant that markets shouldn't expect a further sell-off. They want a strong currency according to official statements. But then they would say that. The US Treasury used much the same language as they desperately tried to devalue the US dollar. As the Fed slashed rates and printed money, the then secretary of the Treasury, Tim Geithner, said with a straight face that the US supported a strong currency.

In China's case they've got other considerations as well. First, they've no desire to ruffle the feathers of the US congress. The US already accuses China of currency manipulation – if indirectly. Similarly, the Chinese are pushing for the yuan to be included as a currency that the International Monetary Fund uses. Even the perception of manipulation won't help their chances.

If the recent deprecation was driven by the market like the Chinese government suggests then those forces are unlikely to abate soon. The new quoting rules mean that the yuan can fall by as much as 10 per cent per week. It might too given that the popular narrative is of Chinese economic weakness – slowing sharply and getting worse.

Similarly, and assuming the other view that the authorities are trying to devalue the currency to boost growth and prevent an economic collapse, it's the same outcome – why would they stop now?

Is a weaker renminbi good news or bad?

A lot of the commentary we read suggests a weaker yuan is a bad thing. It shows the economy in trouble. Note the inconsistency here. If Australia or Europe seeks to devalue their currency then that is good news – if China does it, it's something to fear.

More generally, a currency devaluation works primarily though the trade route, lifting exports, making imports more expensive which in turn redirects spending toward domestic production. It doesn't always happen that way – for example, the Australian context. In China's case it would certainly help more given manufacturing and lower value manufacturing are very competitive. Moreover, Chinese export growth has been very weak lately, down over 8 per cent on the latest figures. Similarly, and while China still enjoys a trade surplus, it is shrinking rapidly. It could be argued that the 20 per cent appreciation of the renminbi is having a dramatic effect.

So to the extent that a weaker yuan lifts Chinese growth. That is a good thing clearly for Australia. Especially when we can dismiss any talk about a weaker yuan leading to a drop off in Chinese demand for Australian commodities, services or goods.

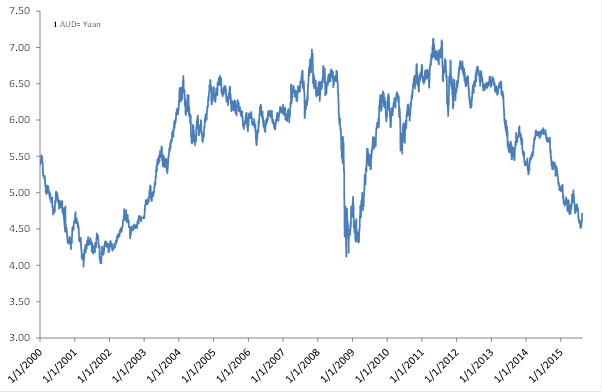

Chart 3: Australian dollar already very weak against the yuan

The main reason for that is because the Aussie dollar is already very weak against the yuan, having declined by about a third over the last few years. Even if the yuan does fall 10 per cent from here, and assuming the AUD doesn't follow, then the cross rate between Australia and China will only be back at levels seen last December – and still about 20 per cent or so weaker than prior to the GFC. So in that sense a weaker yuan isn't bad news and to the extent that it lifts the Chinese economy it's clearly good news.

Whether it ends up being good news or not will depend on how Japan and the US react. The US already complains of a large trade deficit with China, and demands that China either appreciate the currency or buy more American goods. It is possible that the Bank of Japan and the US will simply respond to a weaker yuan by printing more money or leaving rates lower for longer – which of course would spark similar moves across the rest of Asia. It all depends on how the US and Japan choose to act.