What major economies got right, or wrong, after the crisis

The Wall Street Journal

The divergent policy paths taken by the world's advanced economies provide lessons for global leaders navigating difficult post-crisis environments.

The US and UK appear to have gotten something right, while the eurozone and Japan have fumbled. Unemployment rates after the crisis peaked at 10 per cent in the US and 8.5 per cent in the UK, and are down to 5.8 per cent and 6 per cent, respectively. The eurozone rate has climbed in the past few years to 11.5 per cent, while Japan's economy has fallen back into recession.

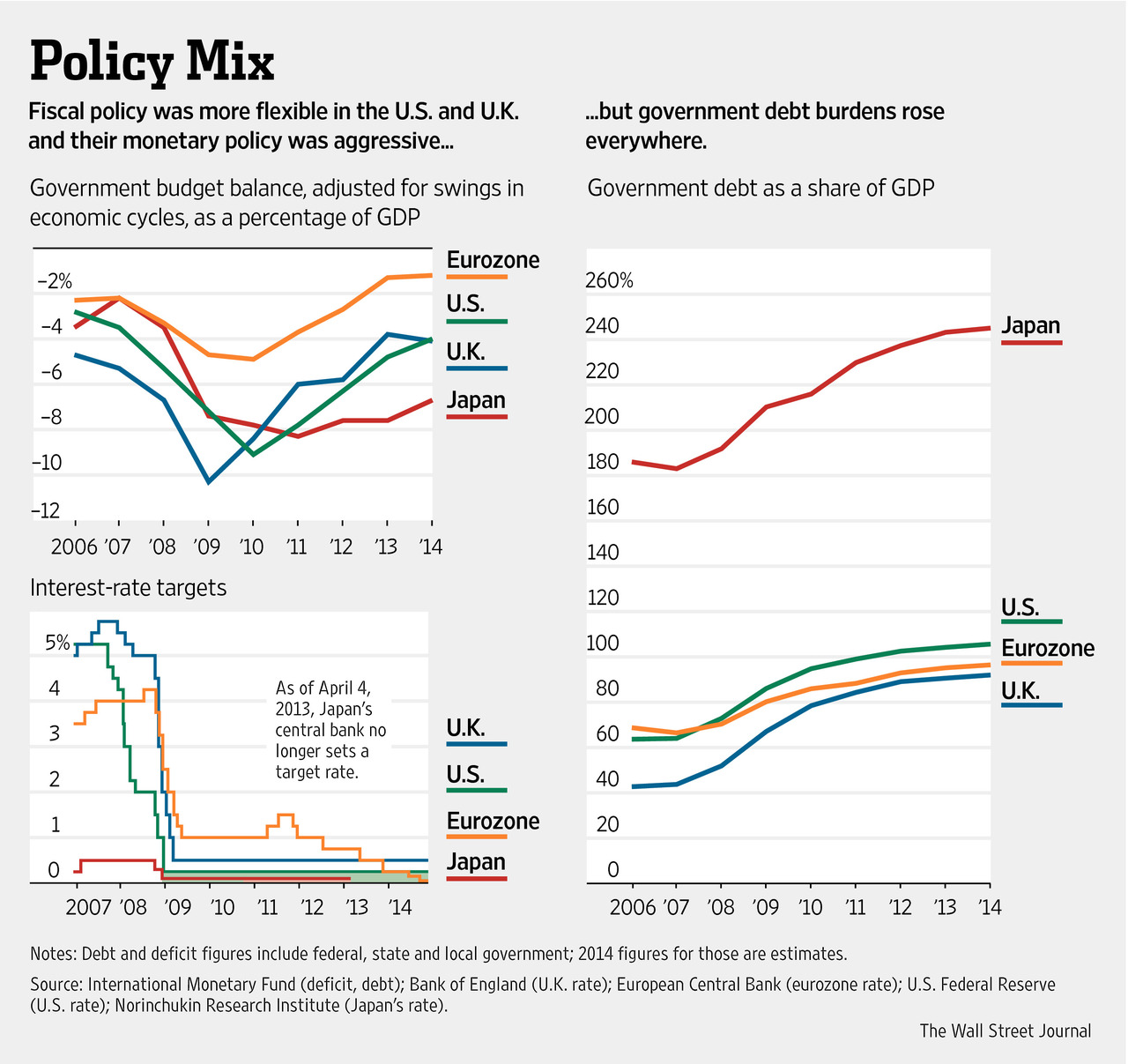

The American and British central banks embraced aggressive easy-money policies early on. Japan lurched toward consumption-tax increases to restrain budget deficits, while Europe moved slowly in addressing weaknesses in banks and stuck to a course of fiscal austerity.

Here are three lessons from this inadvertent experiment in post-crisis policy making:

Quantitative easing helps address a long-standing economic riddle

What can central banks do to help the economy after short-term rates hit the ‘zero lower bound?' When rates are near zero, central banks lose a tool typically employed when the economy is weak: short-term interest-rate cuts. Rate cuts spur borrowing, spending and investment, helping to smooth out the economic cycle by bringing forward activity from a more optimistic future during depressed times.

The Federal Reserve, which cut short-term rates to near zero in late 2008, got around this problem with a policy known as quantitative easing, or QE, which involves buying long-term Treasury bonds and mortgage securities. It aimed to lower long-term interest rates and drive investors to other assets, such as stocks or corporate bonds to spur activity.

The Fed began its first QE program in 2009, and the UK implemented it soon after the crisis erupted. The Bank of Japan embraced the aggressive use of this tool in spring 2013, while the European Central Bank is just beginning to use it.

The potential ill effects of QE that worried many economists -- an outburst of inflation or a new financial bubble -- so far haven't clearly materialized. Inflation is below 2 per cent targets in all four of these economies, but it is getting closer in the US and UK while lagging far behind in the eurozone and Japan. Though some corners of financial markets look stretched, dangerous bubbles aren't yet obvious. The benefits of QE still are a matter of great debate among economists, but given the better fortunes of the US and UK, it seems to have helped the countries that embraced it.

“We have learned that unconventional tools are effective when interest rates hit the zero bound,” said Stephen Cecchetti, economics professor at Brandeis International Business School and a former economist at the Bank for International Settlements, which has been sceptical of QE. “This was far from a certainty in 2008.”

Get your fiscal house in order when you can so you can respond when you must

Fed chair Janet Yellen in a speech this month said governments need to “significantly improve their structural fiscal balances during good times so they have more space to provide stimulus when times turn bad.”

Japan is a case in point. It has run up large government debts, amounting to 1.35 times national output, compared with 0.8 times in the US and UK, according to the International Monetary Fund. Efforts to lower that debt now are interfering with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's campaign to push the Japanese economy out of its long-running funk. In November, the government reported Japan's economy contracted for the second straight quarter due largely to a consumption-tax increase adopted to bring down the debt.

In the US and UK, in contrast, fiscal policy was more flexible -- causing short-term government budget deficits to rise and gradually diminish after the crisis -- than in Europe or Japan. But US policy makers failed to forge agreements to rein in long-run deficits, which could be a problem should another crisis hit.

Quickly get capital in your banks, rather than force them to shrink

Mr. Cecchetti argued at a conference this month that US and European outcomes varied in part because the regions went about recapitalizing their banks in different ways.

European banks increased ratios of capital to risky assets by shrinking portfolios of loans and tilting them away from risky holdings. In other words, they reduced the denominator in these capital-ratio calculations. US banks, on the other hand, increased their ratios by raising capital, the numerator. Firms that raised capital have emerged more willing to lend, Mr. Cecchetti said, and the lesson about financial fragility extends to the broader economy.

A Bank for International Settlements paper shows US banks increased capital by $203 billion between late 2009 and late 2012, compared with $108bn for European banks. During the period, European banks reduced risk-weighted assets by $1.5 trillion, compared with $154bn for US banks.

“Weak banks don't lend, highly indebted consumers don't spend, and businesses with poor prospects don't invest,” Mr. Cecchetti said.

This article first appeared in the Wall Street Journal. Republished with permission.