Time for the hard sell?

When do you call it quits and abandon an investment that hasn't worked out? And when do you take profits on your winners?

The buy decision gets all the attention in investing. People are always hunting around for the next big thing and sharing ideas, but equally important is the question of when to sell. When do you call it quits and abandon an investment that hasn't worked out? And when do you take profits on your winners?

We've written about the sell decision before and discussed it in videos and podcasts. But there's an additional factor that doesn't always get the attention it deserves: the thorny issue of capital gains tax.

You can see the full detail of how capital gains applies to shares on the ATO website. But here's a quick summary.

You'll make a capital gain or loss when you sell shares - provided it's not at the same price you paid (and assuming those shares were bought on or after 20 September 1985). Where you've held a stock for over a year, individuals get to halve the gain, while complying self-managed super funds can knock off 33%.

In any particular tax year, you tally up your realised gains and losses (including any losses you've carried forward from prior years) and that gives you a net capital gain (or loss) for the year. You then add this to your assessable income, and it gets taxed along with your other income.

So when you sell a stock and make a gain, you'll have less to reinvest in another opportunity due to the tax you'll have to pay.

The key point here is that if you choose not to sell, and thereby avoid paying the tax, you'll get to keep using that money - and making returns on it - until you do. In effect, the ATO is providing you with an interest-free loan of the capital gains tax payable - right up to the point that you make the sale and crystalise the gain.

The implication is clear: the shorter your investing time horizon and the more frequently you turn over your stock portfolio, the less money you'll have earning returns for you.

We can see how it might work with an example.

Let's say that five years ago you - an individual with a marginal tax rate of 37% - followed our recommendation to buy CSL back in 2012, investing $10,000 to buy 308 shares. Six years later, the holding has swelled to $64,880 and you're considering taking the profit and moving on.

If you stay put, then you'll keep that $64,880 invested, earning returns and paying dividends. However, if you sell, you'll need to pay $10,153 in tax (the gain of $54,880, halved since you've held for more than a year, times your 37% tax rate), so you'll only have $54,727 to invest in its replacement.

It doesn't sound like much but these differences can really add up over time. Let's look at another example.

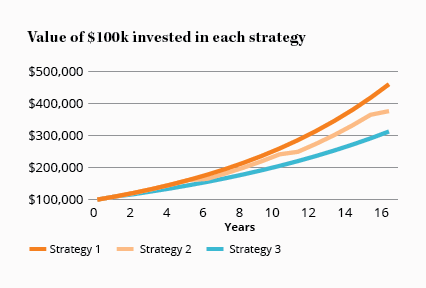

Let's say you're investing as an individual, capable of earning returns of 10% a year before tax and you're starting with a portfolio worth $100,000. Again, your tax rate is 37%, and you're considering 3 possible investment strategies.

1. Buy and hold.

2. Buy and hold for 5 years, at which point you cycle into new investments.

3. Buy and hold for 1 year, at which point you cycle into new investments.

Over the next 15 years, here's what your returns would look like for each strategy:

| $m | 5 years | 10 years | 15 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy 1 | 161,051 | 259,374 | 417,725 |

| Strategy 2 | 149,757 | 226,360 | 341,731 |

| Strategy 3 | 140,962 | 200,026 | 283,827 |

In the first few years there's little difference. Over time, though, the tax payments really start to eat into your returns. It's like compound interest in reverse: each dollar you pay towards CGT is a dollar that isn't earning returns for you in future.

The more you trade, the worse it gets, and that's in addition to all the trading costs.

Of course there will be times when it makes sense to sell - when you find a better opportunity (even after paying any tax), when a stock has grown to have too large a weighting in your portfolio, or when an investment case isn't working out. If any of these apply, don't waste a moment worrying about tax.

But investing works best when you buy and hold a bunch of stocks capable of compounding your capital at high rates of return for long periods of time.

Unfortunately, great businesses, with long-lasting competitive advantages and opportunities to reinvest at high rates of return, are few and far between.

So you need to have the patience to acquire them at the right price - and then hang onto them if you can. Companies like these tend to trade on high multiples, so there's always a temptation to take profits. But if you sell them, not only will it be hard to find something of similar quality to replace them, you'll also have less money working for you.

For readers who wish to plug in their own assumptions and see the effect, we've created a spreadsheet you can use. Just change the assumptions in the top-left hand corner, and the graph will update with new figures. Click here to download it.