The RBA plays a dangerous game with its dollar bet

Reserve Bank of Australia Governor Glenn Stevens fronted the House of Representatives this morning to provide testimony on the state of the Australian economy. The RBA remains optimistic about the outlook but it’s playing a dangerous game that could blow up in its face if the Australian dollar doesn’t depreciate.

The outlook for the Australian economy remains unchanged since August’s Statement on Monetary Policy (The big question mark hanging over the RBA’s outlook, August 8), so I won’t bore you with that discussion again; instead, Stevens had some curious comments to make on confidence, monetary policy and the rebalancing of the Australian economy.

Low interest rates continue to support the Australian economy, particularly housing construction, but the biggest effect of accommodative policy thus far has been to bid up asset prices, particularly in the housing sector.

Stevens notes that this is ‘a big part of how accommodative monetary policy works’. It encourages substitution towards higher-risk assets, improves the balance sheets of households and businesses, and encourages higher lending.

What accommodative monetary policy has failed to do -- at least to the degree necessary -- is lower the exchange rate. So far the dollar -- which admittedly is down 10 per cent since April last year -- has not done much to help achieve more balanced growth.

Stevens appears to be putting a lot of faith in ‘animal spirits’, noting that confidence is something that monetary policy can’t directly cause and greater confidence is needed to encourage greater investment.

Many firms remain happy to deleverage and refinance existing debt; they’d rather pay dividends and return capital to shareholders than implement risky growth plans. As a result, non-mining investment (outside residential construction) remains subdued.

What’s curious about Stevens’ comments is that monetary policy does affect confidence -- of both the household and business variety. The thing about confidence is that it is a function of other factors -- consumer measures are largely driven by the state of the labour market.

By shifting incentives to lenders and borrowers, monetary policy must necessarily have an influence on confidence. If confidence is subdued, isn’t that an indication that there remain a range of underlying problems within the economy? Isn’t that an indication that perhaps monetary policy has not done enough to overcome inadequate demand or encourage investment?

In Australia’s case, the non-mining sector is cautious because the dollar remains uncomfortably high. For years it’s suffered at the hands of the mining investment boom, which saw interest rates and the exchange rate rise to a level that left them largely uncompetitive.

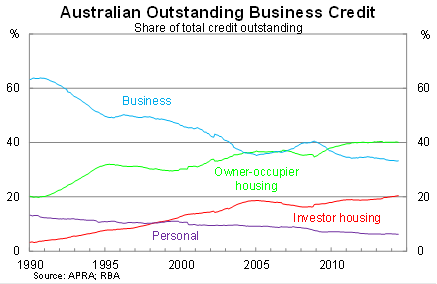

Furthermore, lending markets have failed Australian businesses. Since the end of 2008, mortgage lending has accounted for the entire rise in outstanding credit. The non-mining sector -- which predominantly relies on domestic banks or equity for financing -- has been starved, resulting in job cuts and a further loss of competitiveness.

Our banking sector has gone all in on mortgage lending, which carries a lower risk weight on its balance sheet and allows for higher leverage and greater profits. Amazingly none of the banks have realised that by undermining the very business sector that pays the wages of a vast majority of Australian workers, they have inevitably increased the riskiness of their mortgage holdings.

Now obviously none of this is set in stone; the outlook remains highly uncertain. The dollar could finally fall on the back of softer commodity prices and a lower terms-of-trade, easing some of the competitive pressures on the non-mining sector. The resulting boost to confidence would then feed through to investment.

But isn’t it fair to say that Stevens is being a little complacent about the dollar?

The upcoming task for the RBA is very simple: they need to lower the dollar and encourage greater business investment. The easiest way to achieve this would be to introduce macroprudential policies, which would make business lending more appealing, and then lower rates further to kill off support for the Australian dollar.

As it stands, the RBA is playing a very dangerous game. It openly admits that it has no idea how big the mining investment collapse will be -- neither does anyone else -- but the potential ramifications of getting policy wrong are profound.

If mining investment collapses before the dollar has fallen sufficiently, the non-mining sector will be in no position to fill the gap and rebalance the Australian economy. That scenario would inevitably result in Australia’s first recession in 23 years.