Market Watch

It would be remiss not to comment on what has clearly been a very ‘eventful’ week.

The leads from US markets have certainly put pressure on global markets as funds scramble to buy risk protection (options markets), the risk-free rate (US 10-year Treasury) and stores of value (gold).

The triggers for this week’s events have been plentiful – and yet we will still never truly know why the US markets fell out of bed. However, some of it can be attributed to macroeconomic data released last Friday night. Most notably, the data drop revealed the average hourly earnings figure of 2.9 per cent was at a record high for the post-GFC era. This suggested that inflation would finally materialise in the US, causing the market to finally take the forecasted three rate rises in 2018 seriously.

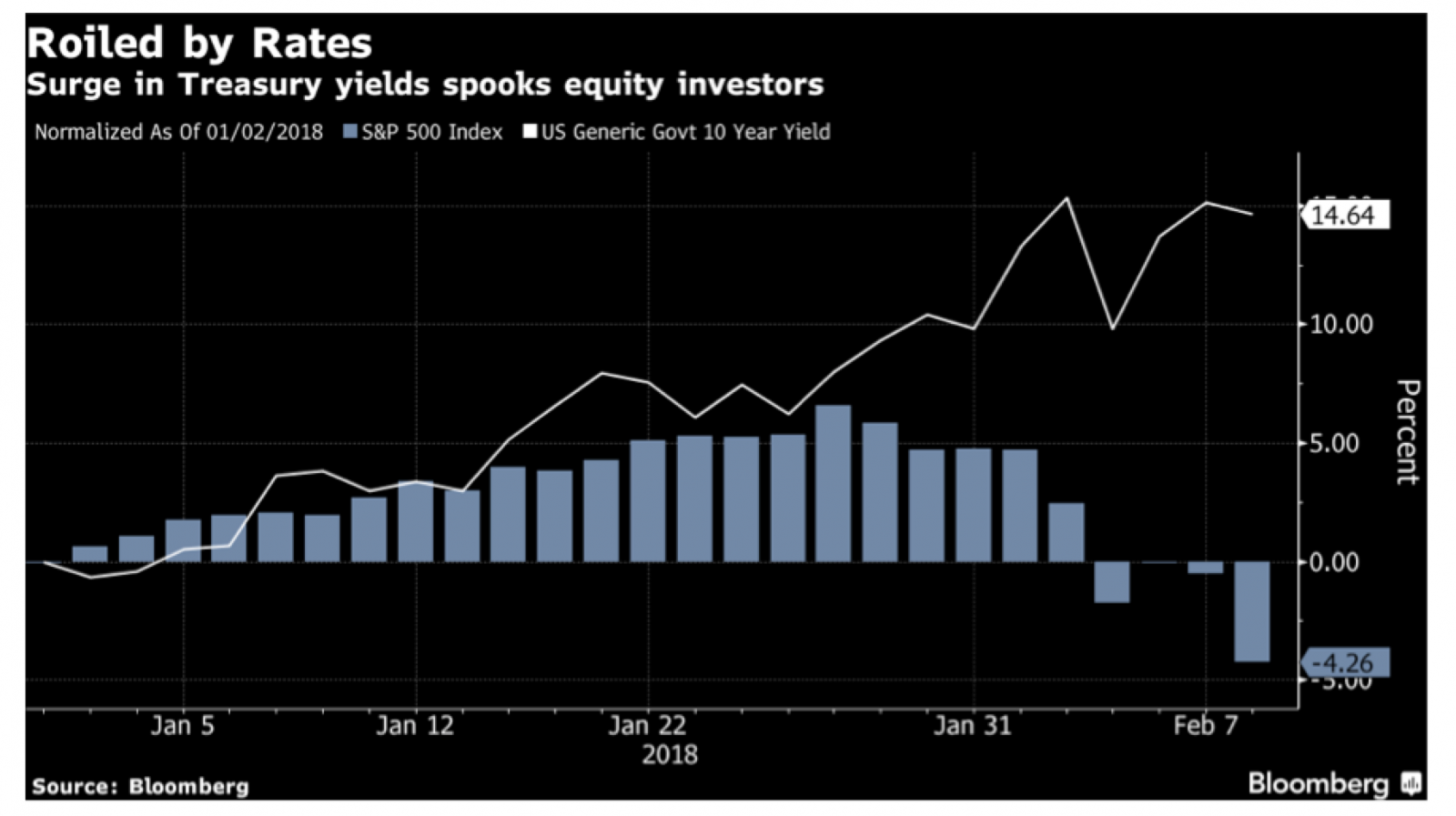

The Bloomberg chart below illustrates the returns in the S&P 500 and the US 10-year over the past month:

Looking at this week logically, if the US were to increase rates by 25 basis points (bps), three times in 2018, then a 75bps increase would see 10-year Treasury yields rising by the same amount. That suggests the US 10-year would come in at around 3.3-3.5 per cent by December, an attractive risk-free rate, making it more understandable that funds would flow out of other markets to soak up these yields.

The two large drawdown days this week caught many off-guard. Investors can often be caught off-guard by intraday spikes. But this week’s volatility hasn’t been seen in almost three years.

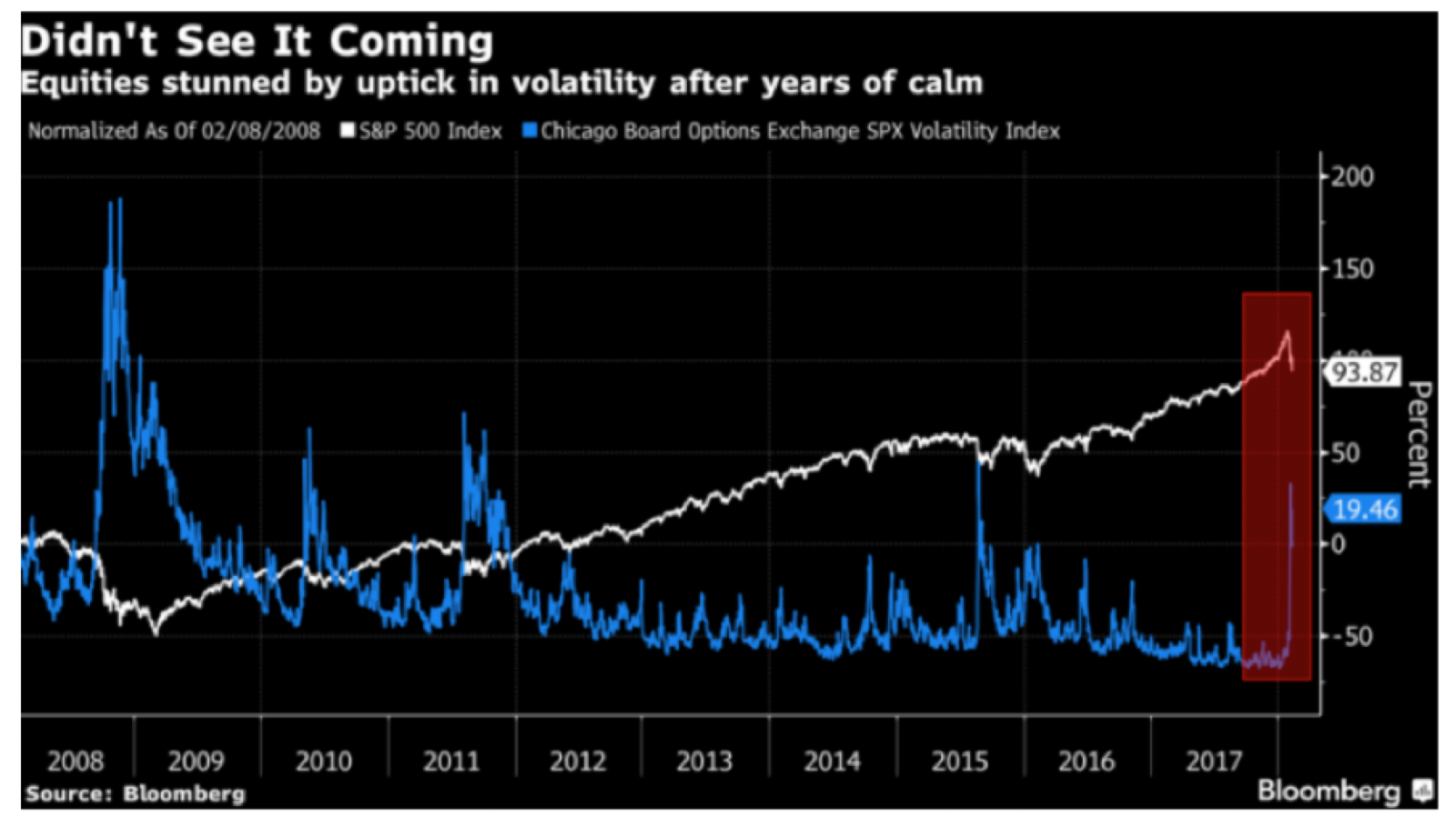

Another Bloomberg chart perfectly shows the relationship between this week’s sell-off and the mass pickup of put options as the CBOE Volatility Index spiked. The index, known as the VIX, is a gauge for short-term implied volatility in the S&P 500.

Interestingly, the spike in the blue line in 2015 boiled down to high asset prices without an underpinning of global growth. China had slowed for the third successive year, and Europe and Japan also remained sluggish.

In 2018, however, the global economy seems to be starting to power ahead. Europe and Japan have been singled out as likely bright spots, while China last year experienced its first year of GDP expansion in over four years.

This highlights the difference between this week’s volatility spike and those of the past eight years.

This week’s market movements weren’t due to a geopolitical crisis, such as the Eurozone crisis of 2011/2012, or a macroeconomic issue like sub-prime mortgages and overleveraging in equities that caused the GFC and then aftershocks in 2010.

This year, we are facing the facts that US monetary policy is heading back to a ‘normalisation’ rate and that means reweighting to reflect this next paradigm. This isn’t panic selling or the start of something sinister; it’s just normal market behaviour that has been seen many times over the past century and a half of market trading.

Moving on from market trading, there were a few Australian macroeconomic events this week that change the cash rate outlook. But rates will not change in 2018.

The RBA board meeting on Tuesday, the Statement of Monetary Policy (SoMP), and RBA Governor Philip Lowe’s speech to the Economic Forum, all deliver the same conclusion, when taken together or separately.

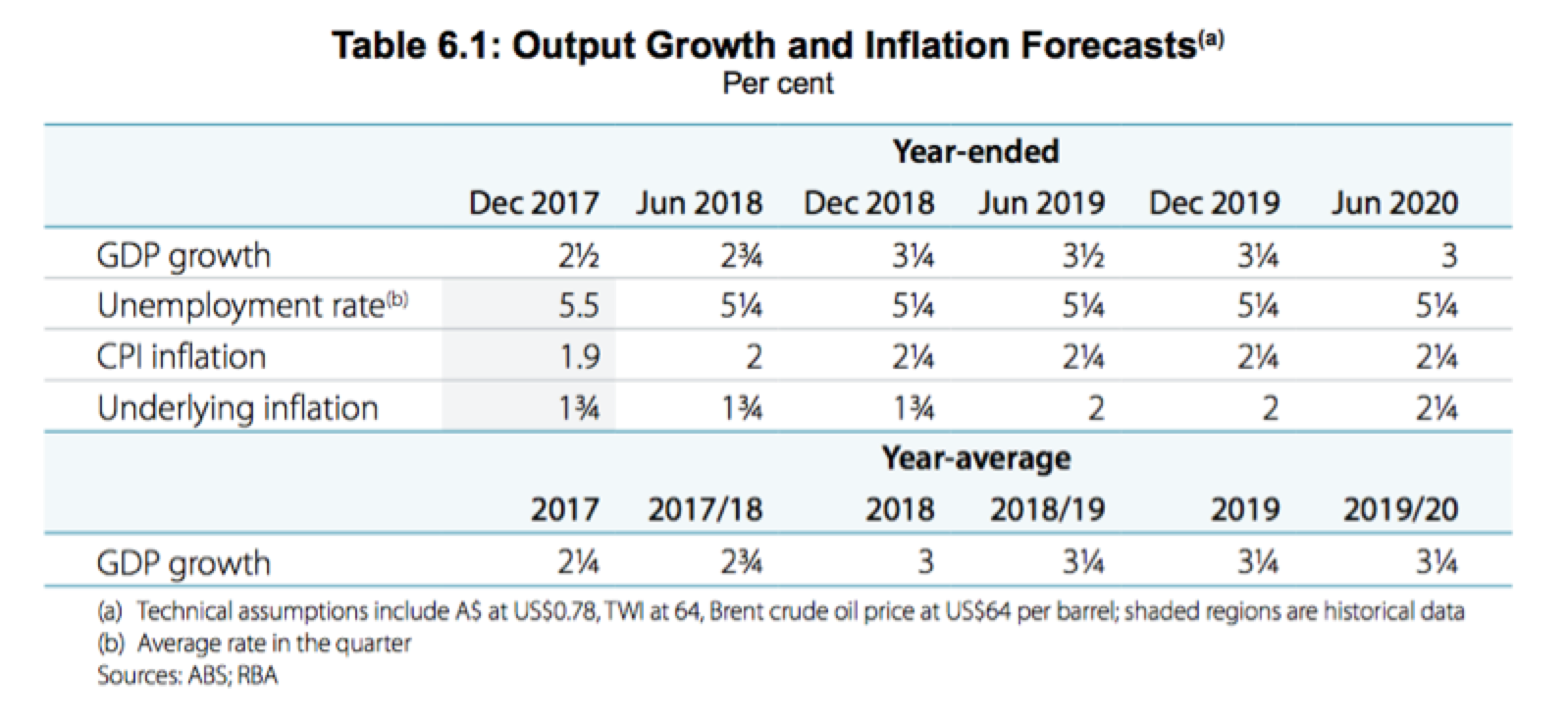

The Board statement and the SoMP are perfectly summarised by the outlook table from the SoMP release:

The forecasts are for growth to be above 3 per cent come December, unemployment to fall slightly from current levels, and still stagnating inflation.

What’s hard to see is how a forecasted growth rate this high won’t positively impact the other two variables more than is being forecasted. That puts into question which of these forecasts will prove true: GDP above 3 per cent leading to better inflation and employment, or will it be the other way around? In any case, the main point is core inflation will remain below the 2-3 per cent target range for the foreseeable future.

However, the following statements from Philip Lowe’s address ties all of this together:

“We are still some way from what could be considered full employment and our central scenario for inflation is for it to remain below the midpoint of the medium-term target range for the next couple of years…

We expect to make further progress in reducing unemployment and having inflation return to the midpoint of the target range. If we do make that progress, at some point it will be appropriate for interest rates in Australia to also start moving up. While we do expect steady progress, that progress is likely to be only gradual…

Given this, the Reserve Bank board does not see a strong case for a near-term adjustment in monetary policy.”

The SoMP also forecasted core inflation at 2.25 per cent in June 2020.

The prospect of a rate hike in 2018 looks impossible based on Lowe’s comments above. The comments also raise the possibility that in 2019, we may also see no change.

This would be good news for mortgage holders. But it does beg the question, what will snap Australia out of its low inflation environment if the RBA isn’t going to get involved?