Kohler's Week: What just happened?

Last Night

Dow Jones, down 0.07%

S&P500, up 0.07%

Nasdaq, up 0.32%

Aust dollar, US71.7c

What just happened?

The sharemarket, globally and in Australia, has now got back what was lost in the panic of Monday and Tuesday. But as I write to you this morning we are still sitting on corrections of 12 per cent here, 9 per cent for the MSCI, 7 per cent for the US and 40 per cent for China since June 12 – including 19 per cent down in the latest leg of the correction in Shanghai in August, including 10 per cent up in the past couple of days. So while it's clear that what happened earlier this week was some kind of robotic fit, mainly done by computerised trading, the question remains: was this week's action a bout of volatility within a new bear market that's a couple of months old, or was Monday the bottom of a bull market correction?

To avoid burying the lead, as we used to say in journalism class, I don't think a bear market has begun, but I don't know whether the correction has finished. Possibly not. There remain some significant problems in the global economy, with China topping that list, and there are two big things going right: the American economy and the oil price (recessions are never preceded by a lower oil price, but recessions can be caused by rising oil prices). So what I want to do this morning is try to make sense of what's going on.

To cut to the chase again, I'm beginning to think that the least appreciated factor, but possibly most important, is the collapse of confidence in national leadership – not just in Australia, where the problem is reinforced most days – but everywhere. In that I'm not just counting politicians, but also central bankers and economists generally, who have become the captains and crew of the economic cruise liner in the absence of politicians, who joined the guests on the dance floor long ago.

I have been re-reading JK Galbraith's “The Great Crash, 1929” this week and it's clear that the stockmarket crash in 1929 was the simple and inevitable result of a price bubble, as with Shanghai this year, but as Galbraith writes: “ .. economists and those who offered economic counsel in the late twenties and early thirties were almost uniquely perverse. In the months and years following the stock market crash, the burden of reputable economic advice was invariably on the side of measures that would make things worse.”

Specifically, both President Hoover in 1930 and 1931, and the campaigning Roosevelt in 1932, maintained two destructive dogmas: the need for a balanced budget and the gold standard. So as the budget went into deficit in 1930, taxes were increased and spending was cut, and despite rampant deflation, fear of inflation kept America's currency tied to gold and thus unable to devalue. It was exactly what happened to Greece after 2010 – an inability to devalue plus austerity budgets equals depression.

As late as 1933, Herbert Hoover wrote: “It would steady the country greatly if there could be prompt assurance that there will be no tampering or inflation of the currency; that the budget will be unquestionably balanced even if further taxation is necessary; that the government credit will be maintained by refusal to exhaust it in the issue of securities.”

As we now know, that was 100 per cent wrong, and Roosevelt's “New Deal” embodied in the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 in a sense admitted as such. It took a decade, and then winning a war, to restore some confidence in the Government, and even then there was intense ongoing pressure to make central banks independent from political influence – except, of course, in China. And the admission of error embodied in the New Deal, further reduced confidence in the leadership.

Ben Bernanke, a student of the Great Depression, became the world's most powerful economic leader – except that his only tool was, and Janet Yellen's still is, monetary policy. But he did what he could, and did not defend the currency, as Hoover did, and quickly cut the interest rate to zero and printed money.

At first Governments everywhere also learned from the mistakes of 1930-1933, and did not defend their budgets, but the ammunition was quickly spent and then politicians retired to the sidelines, from where they have generally made fools of themselves. The exception was Europe, where Germany has been recapturing past “glories” (or should be opportunities) and imposing its culture on the rest with austerity budgets, driving many into a 1930s-style depression.

But look, the greatest danger we face as investors is the incompetence of economic political leadership and, flowing from that, a lack of confidence in it.

This is pretty obvious in Australia. I pointed out last week that for most of the past decade, Oppositions have been more popular than Governments, whoever has been in power, which is devastating for business confidence. This was also on display this week at the National Reform Summit, where a succession of business lobbyists and representatives got up and lectured the Government about what they should do.

But it's not just here: investors and business people have little faith in politicians around the world at the moment.

But, as Gerard Minack wrote this week: “But there has been a deep faith in the ability of monetary policy to both lift asset prices and, ultimately, generate an adequate inflation rate over the medium term.”

That faith in the Fed, and Glenn Stevens' RBA, has essentially provided all of the investment gains on the past five years – outside the US, global earnings per share, on average, have fallen, yet prices have gone up 40 per cent: that is, the increase in share prices has been entirely due to an increase in the price earnings ratio. In the US eps went up 30 per cent while share prices rose 60 per cent, so the re-rating was almost as extreme there, except that earnings did rise thanks to cheap labour and energy.

The global re-rating of shares that we have enjoyed has been entirely a function of two things: confidence in central banks and the effect of disinflation on bond yields, which improved asset values by lowering discount rates.

This is perhaps an over-simplification, but the way I see it is that share markets have been lifted by a weird combination of low inflation suppressing bond yields, and confidence that central banks will be able to fix it and get inflation up.

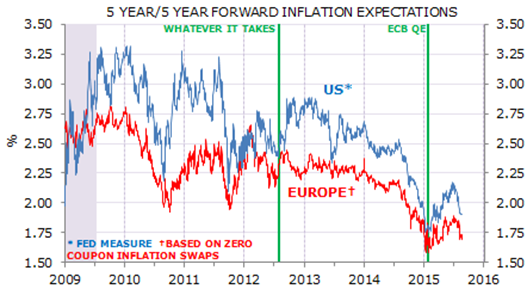

As Gerard wrote as a follow up to the quote above: “If investors start to doubt that (that inflation can be revived) – and the decline in break-even inflation rates suggests concern (see graph below) – then things could get significantly worse.”

The problem is that inflation is not responding normally to monetary stimulus. Why? Two things: technology and debt. The former I have banged on about many times, and is self-explanatory: the effect of automation, 3D printing and cloud computing is clearly to reduce costs, while intense competition regulation ensures that it is mostly passed on though lower prices.

The problem with debt is best summed up by Van Hoisington, the great bond investor and – still – bond bull: “We believe the fact that over-indebtedness of the United States and the world is contributing to the lack of global demand, because people have borrowed and spent, and that means they can't spend that money in the future, they have to try to repay it. And that's at all levels – corporate, individual, governments – and that is sort of an over-arching restraint on economic activity. And the wonderful thing is that the Federal Reserve and other central banks can't do anything about it.” Wonderful for him as a bond investor, that is.

In fact three weeks ago in this email I went a bit further, discussing that, in fact, monetary policy has stimulated speculation, not productive investment. I wrote then: "The suppression of interest rates, the manipulation of exchange rates, increasing taxation and a drought of infrastructure investment (except in China) is having the inevitable result – slower growth rates."

Let's drill in more detail into what's happening. The trigger for the correction was clearly China, so let's start with that.

1. China

The collapse of the share market in June was no mystery: it went up too far; it fell, just like in 1929. The direct effect of the crash on the economy is probably fairly minimal. The problem is that investors' confidence – both in China and around the world – in the Chinese Government's ability to manage the economy has been severely shaken.

The Communist Party leadership stupidly acted as cheer-leaders for the bubble, asserting that it supported the reform program.

Then its frantic efforts to prop the market up in June led everyone to suddenly realise that the Chinese Communists had not really had a conversion to believing in market forces and didn't really have faith in, or even an understanding of, the market.

And then even worse, the intervention failed.

And then the decision to devalue the currency and loosen control over it came as a complete shock to markets and produced a further drop in confidence. The People's Bank of China did a terrible job of explaining what it was up to, so puzzlement was added to surprise.

So the idea that the Chinese leadership is implementing a carefully thought out plan has gone out the window. They're making it up as they go along, and are motivated mainly by self-protection and power-preservation. More mistakes can be expected, along with more capital flight and market volatility. Meanwhile the recession in China's heavy industries continues and housing construction has peaked.

Any investment strategy that relies on everything going well in China is a risky one.

2. America

We need to always keep in mind the unique strengths of the American economy: unlike China, it has the most efficient markets in the world for labour, goods, capital, services and information; it has cheap energy and relatively cheap labour now; a growing population due to immigration which brings in cheap workers and entrepreneurs; aggressive innovation; an entrepreneurial culture and a vast domestic consumer market. While many countries have some of those things, no other country combines them all.

Add to that six years of zero interest rates, neutral fiscal policy, incredible amounts of cash on corporate balance sheets and a six-year bull market in equities, and it's no surprise that second quarter GDP growth was revised up on Thursday from 2.3 to 3.7 per cent. That's much more like it.

Fixed investment was upgraded from 0.3 to 5.3 per cent growth and consumption lifted from 2.9 to 3.1 per cent. Also employment is growing more strongly than the population, so unemployment will continue to fall. So, all good, except …

Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders are slugging it out for the right to slug it out for the Presidency: dumb versus dumber. I presume we'll end up with Jeb Bush versus Joe Biden or Hilary Clinton, but the theme of minimal confidence in political leadership is very much intact in the US.

3. Australia

UBS put out a report this week with the arresting headline: “Is Australia already in ‘recession'?” In it UBS economist George Tharenou predicted a negative GDP number for the June quarter, because of low wages, weak corporate profits, and the collapsing terms of trade.

The reason for the quote marks around the word recession is that Tharenou is calling it a “phantom recession”: “Rather than a broad downturn including housing & consumption, a ‘recession' would more reflect the timing of an intensifying (private & public) capex cliff in 2015, ahead of the big boost from the full ramp-up of LNG exports in 2016.”

Unemployment has already hit a 13-year high of 6.3 per cent, jobs are likely to drop further after the “capex cliff”, and worries about China, plus the wealth effect of the share market correction, could see a drop in consumer and business confidence.

What George didn't mention is the effect of today's big Saturday morning theme: low confidence in political leadership.

The problem for Australia is that this is becoming entrenched – it is no longer possible to see disdain for political leaders as a fleeting aberration, like Bill McMahon's Prime Ministership, or Mark Latham's leadership of the ALP.

For example, I was driving to work this week and on the radio there was the story that the Victorian Treasurer had said the Government would borrow within its existing AAA credit rating to fund some infrastructure. Then the shadow Treasurer came on and declared that the sky was about to fall, invoking memories of Cain and Kirner. Sensible discussion about the appropriate level of debt for infrastructure investment was thereafter impossible.

Politics has become an extreme sport, where no good idea goes undenounced, whatever it is. It's always been so to some extent, but it seems worse right now. It's probably the media's fault.

Anyway, the emptiness of political discourse is weighing on confidence and it is becoming a serious issue. I suspect the cycle can only be broken by a few courageous individuals – possibly just one – daring to be normal.

BHP

As a consequence of all of the above (low growth in China, low interest rates), BHP Billiton has turned itself into an income security. Speaking personally, this is a very big surprise and not a little disorienting, having spent a lifetime reporting and commenting on this great Australian company in the complete absence of any discussion of its dividend. Dividend? What's that? The yield, franking and payout ratio have been quite irrelevant.

As a result, I opened our interview with BHP CFO Peter Beaven this week as follows: “Paying a 62 cent dividend with earnings per share of 36 cents at the bottom of the cycle when the company should be investing is pretty ridiculous, isn't it?” (I always try to open these sort of interviews with a straight right to the jaw, just to keep them on their toes. Eureka interviews are designed to inform you – a different matter).

Beaven's answer: “Well, I would say that we are investing and we invested $11 billion of our share last year, and that investment plus the investment that's come before it allowed us to increase copper equivalent production by 27 per cent over the last two years, so I think that we've done pretty well in that regard. I think that going forward it is a healthy dividend and we're proud of that, but at the same time we continue to invest in the company.”

Is this change in BHP good or bad? Unambiguously good. BHP's history has been all about building and buying things: sometimes they are fantastic, like Escondida or Mt Whaleback, but a lot of the time the mines are duds, and you don't find out for 10 years. Focusing on costs and paying cash to shareholders is a vast improvement.

But despite the focus on dividends, the most interesting part of the interview for me was when he started talking about their hurdles for decisions about investing in new projects, greenfield or brownfield:

“…the real hurdle of course is a buyback and so we run a buyback alongside any other decisions we make around capital as if it's an investment decision because it is. You can invest in this or you can buy this stock in this company that happens to be called BHP. The risk profile of this company is different from this project and we understand that and we build that in. And so that's how we think about it.”

He wouldn't tell me what that meant the hurdle rates actually were, but it opens a window into the way the modern BHP under Andrew Mackenzie is approaching investment. It's all about capital management: either you pay the cash as a dividend or if it's to be invested it has to beat the returns to shareholders from a buyback. It is a complete change in mentality. The old BHP management would have decided which projects they wanted to do and found a way to do it; Mackenzie's BHP is all about shareholder value.

Investors Central

This is in line with my policy of bringing you investment ideas that are unlisted, and therefore not subject to the wild moods of Mr Market.

I agreed to have a coffee this week with a young (well, 43-year-old) bloke from Townsville who has a money-lending business there. And as I listened to Jamie McGeachie's story, I thought: “I've got to share this with Eureka members, he's gold”, so I whisked him upstairs to the studio and recorded an interview. I wanted you to see and hear him – a sheer delight! It was too late for a Eureka Interactive one, where you could ask questions too, so it's just me and him.

He started out in the family pawnbroking business and expanded into finance broking, as well as lending the family's own money. Then in 2010 he launched what he called Investors Central to raise preference share capital to fund the loan book, which now sits in a vehicle called Finance One.

The headline summary of Jamie's business is that he now has a national loan book of $42 million, sold entirely through brokers, and funded entirely by preference shares in Investors Central, backed by a prospectus. Maximum loan is $50,000, and they're all for cars. There's no limit on investment in the prefs and the minimum is $10,000. Terms are fixed. Interest ranges from 9 per cent for one year to 16 per cent for five years. The prefs are unsecured, but they rank ahead of ordinary shares (which are 100 per cent owned by Jamie) in the event of bankruptcy of the business.

The default rate on the loans is 1.5 per cent but he is budgeting for much more than that. He has a very unusual way of lending – he develops relationships with all the borrowers, sending Christmas cards and Scratchies to them on their birthdays. Repossession is rare, but it does happen.

Fascinating business. He is five years into a 20-year plan to build a very big business, and I have no doubt he will succeed. You can watch or read the interview here.

Carsales

I did two interactive interviews this week – one with Greg Roebuck of Carsales, which is a mature business in Australia that is rapidly expanding both offshore into vehicle classifieds and into other businesses in Australia. The main, but far from only, overseas expansion is in Korea, and the most interesting diversification in Australia is into the finance business, by buying a finance broker called Stratton and taking a share of the peer-to-peer lender Ratesetter. Carsales has also launched a property site called homesales.com.au, which is focused on investors, but Greg plays that down.

As usual Greg is frank and interesting. You can watch/read the interview here.

Medical Developments

This was my second interview with John Sharman of Medical Developments International (ASX code: MVP) this year, but it's a very interesting business and worth keeping in touch with. MDI has an asthma inhaler business that provides cash flow, but the excitement is all about the product called Penthrox – an analgesic inhaler used in ambulances. The ambos like it because it's not an opiate and therefore doesn't have side effects or adverse reactions, and is quickly effective and easy to administer.

As John explains in the interview, he has a term sheet agreed with a big European pharma to distribute the product there, and he's already selling it in the UK. He's also working hard on getting it into the US. If he pulls it off, the potential is enormous … if he pulls it off.

There's also growth potential in Australia by getting the product into hospital emergency departments.

Watch/read the interview here.

Readings & Viewings

This was a great summary on the ABC's Law Report of the astonishing Roseanne Beckett case. She was awarded $2.3 million this week for “malicious prosecution” after spending 10 years in jail. This is an interview with journalist Wendy Bacon, who has been following the case for 20 years.

An article on the same subject, if you're interested in learning more about it.

“Honest Movie Trailers” does Fury Road.

How to use a Tim Tam as a straw.

Robyn Williams: The media's war on science.

China's market chaos is due to an exodus of sea turtles.

Five things about China that drive investors crazy.

Nice piece about what's really going on in China (not sea turtles, really).

China's ‘major correction', charted and extrapolated.

The seasonality of New York's dog poo.

The Fed versus PBoC – which central bank comes out on top?

The truth about the labour mobility provisions in the China FTA still has not come out.

The ugly truth about Australia's economy

Ashley Madison was a bunch of dudes talking to each other, data analysis suggests.

China and the return of the ‘yellow peril' – the muddled economics of scapegoating

As the US economy recovers, traffic congestion is making a comeback. I know the feeling!

The reason you saw the Virginia shooting video, even if you didn't want to.

Really interesting piece about Las Vegas and Pyongyang.

The reaction of five men forced to watch The Bachelor.

Freakonomics has done a two-part series on modern marriage.

A lost short story by John Steinbeck!!

Tony Hunter sent this to me, with the subject: Attention Van Morrison fans, which I am!

Sony to offer commercial drone services in 2016

Lesson for the Fed: All 15 central banks in the OECD that raised rates after the 2008 crisis had to cut them again.

Charts: This may be the start of the world's next financial crisis.

The approval of female “Viagra” is nothing short of a disaster.

Really interesting piece about the political impact of the heatwave that's going on in the Middle East. I had no idea!

Barrie Cassidy: where's our ambition? Get on with reform!

The use and abuse of dividend strategies.

Last Week

By Shane Oliver, AMP

Investment markets and key developments over the past week

Share markets have gone from goodbye to good buy over the last week. The turmoil in global share markets continued into the past week, but signs of stabilisation and improvement gradually started to appear resulting in several share markets actually rising over the last week. Believe it or not, this started in Australian shares on Tuesday as buyers saw value around the 5000 mark on the ASX 200 and then continued as China eased monetary policy, Fed officials indicated that a September interest rate hike was looking less likely if global growth worries persist and global investors refocussed on good US and Eurozone economic data. Commodities traced out a similar path, falling initially before rebounding with metals and oil up over the week. The turn up in share markets also saw bond yields rise and the $A recover partially from a low of $US0.7050 early in the week.

From this year's highs to their lows in the past week major share markets have now had the following falls: Chinese shares -43 per cent, Asian shares (ex Japan) -23 per cent, emerging markets -22 per cent, Eurozone shares -18 per cent, Australian shares -16 per cent, Japanese shares -15 per cent and US shares -13 per cent. While it's too early to say we have seen the lows, there are several positive signs in that: shares have become quite cheap again, investor sentiment on some measures has fallen to bearish extremes that are often associated with market bottoms and the monetary easing in China along with signs that the Fed is prepared to delay (yet again) its planned rate hike have helped provide a circuit breaker to the falls.

China moved into gear big time over the last week with a cut in both interest rates and required bank reserve ratios, liquidity injections, capital injections into some banks and an expansion of the program that allows local governments to swap their higher cost debt for cheaper debt. The interest rate and reserve ratio cuts were long overdue. China's official interest rate of 4.85 per cent was leading to borrowing rates for small and medium sized companies that were way too high at a time when producer prices are falling. China is the only major economy with lots of fire power to provide stimulus and also the only one that needs to. Further easing in China – including fiscal stimulus is needed and likely because the last thing China wants is the sort of social unrest that will flow from a hard landing in its economy.

Comments by Fed officials clearly indicate that they are aware of the risks to US growth and inflation from uncertainty regarding global growth and weak commodity prices. In fact the third most powerful official at the Fed, William Dudley indicated that an interest rate hike in September now “seems less compelling.” This is a good sign and consistent with the view that the Fed is not going to do anything that mucks up the global economic recovery and threats US growth and inflation.

The Australian June half profit reporting season is now complete, and although results have been a little disappointing they have not been disastrous. 43 per cent of companies have beaten expectations and 59 per cent have seen their profits rise from a year ago which is okay, but it's well down on what we have been seeing in the last few reporting seasons. While profits fell nearly 2 per cent over the last financial year this was driven by a 28 per cent slump in resources profits with the rest of the market seeing profit growth of around 7 per cent driven in particular by general industrials, building materials, retail and health care stocks although the latter disappointed relative to expectations. Key themes have been constrained revenue growth, strength in companies connected to home building and NSW and solid growth in dividends with 57 per cent of companies raising dividends. Weak guidance saw profit growth expectations for 2015-16 revised down to around 2 per cent, but again with the strength coming from non-resources companies which should continue to benefit from low interest rates and the lower $A.

Major global economic events and implications

US economic data was good. Home price data was on the soft side but it's still trending up and more importantly consumer confidence rose strongly in August which is positive for consumer spending and orders for capital goods orders rose solidly which is positive for business investment, June quarter GDP growth was revised up to 3.7 per cent annualised and jobless claims fell. With inventories likely to act as a drag on US growth in the current half year, the US economy is still far from strong/inflation threatening growth but it does look solid. So while the Fed may delay hiking rates, it's still likely sometime in the next six months.

European economic news was also good with French and German business confidence up, money supply growth up and bank lending growth accelerating further all pointing to stronger growth in Europe.

Japanese data for July showed a strong labour market with the jobs to applicants ratio at its highest since 1992, but soft household spending and core inflation too low at 0.6 per cent yoy.

Australian economic events and implications

On the economic front in Australia, the main focus was on business investment and here the news remained weak. Business investment fell further in the June quarter and investment intentions point to around a 25 per cent fall in business investment in the current financial year with mining investment falling 38 per cent and non-mining investment also falling by around 8 per cent. This is little different from the outlook seen in the March quarter capex survey, but the failure of non-mining investment to improve remains a concern. Pressure is likely to remain on the RBA to cut rates again.

At last petrol prices have really started to fall back into line with where the global oil price and $A suggest they should be with prices falling to around $1.15/litre in the last week. The move from around $1.40/litre will save the typical family nearly $9 a week or $455 a year if sustained.

Next Week

By Craig James, Commsec

Spring tsunami

At the change of every season, investors are subjected to a barrage of new economic data and events. In the coming week around a dozen indicators will be released in Australia in addition to a Reserve Bank Board meeting.

The week kicks off on Monday with a raft of indicators. The Housing Industry Association releases new home sales at a time when developers are indicating that home building is near its peaks. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) releases the Business Indicators publication covering profits, sales, stocks and wages. The Reserve Bank releases private sector credit data (effectively, outstanding loans). And TD Securities and Melbourne Institute release their monthly gauge of inflation.

The Reserve Bank Board meets to decide interest rate settings on Tuesday. But barring a complete surprise, no change in rate settings is likely. The statement accompanying the decision could be short, although there is scope for a few words on the sharemarket volatility.

On Tuesday, the ABS releases data on building approvals, government finance and the balance of payments. CoreLogic RP Data releases the August home value index. Home building approvals probably rose by 1 per cent in July while home prices may have lifted 0.7 per cent in August.

Also on Tuesday the usual weekly consumer confidence survey is issued by ANZ and Roy Morgan.

On Wednesday, the ABS issues the quarterly economic growth estimates in the National Accounts publication. At this early stage we are tipping growth of between 0.4-0.6 per cent in the quarter and growth of 2.2-2.4 per cent for the year. Growth is seemingly below “normal”. But that assessment of “normal” is being reconsidered.

On Thursday, the ABS releases data on retail spending as well the trade (exports and imports) data for July. We expect a modest 0.3 per cent lift in retail spending. But the trade deficit probably remained significant near $3.6 billion. Higher imports actually suggest a healthy economy – more spending.

And on Friday, the ABS releases the July publication of Overseas Arrivals & Departures. The publication includes tourist movements as well as migration flows. China is getting closer to overtaking New Zealand as our largest source of tourists.

Employment data in focus in the US

The spotlight shines solidly on the US employment data to be released on Friday. A solid lift in jobs will see the odds shorten for a rate hike in September.

But the week kicks off in the US on Monday with the release of the influential Chicago purchasing managers index.

On Tuesday, the ISM manufacturing index is released in the US. A reading of 53 is tipped – above the 50 line that separates contraction from expansion. Data on construction work is also issued with the monthly figures on new auto sales. The usual weekly chain store sales figures are also released.

In China, the “official” purchasing manager indexes are released on Tuesday. That is, the National Bureau of Statistics will release the surveys covering both manufacturing and services sectors. The surveys are more reliable than the private sector surveys and the survey sample is much larger.

On Wednesday, the ADP series of private sector payrolls is issued – the precursor to Friday's official job data. Economists expect job growth of around 205,000 in the month. Revised data on labour costs and productivity is also released on Wednesday together with estimates of factory orders. The weekly reading of housing finance is also issued on Wednesday.

On Thursday new estimates on international trade (exports and imports) are issued for July. The trade deficit may have widened from US$39.8 billion to US$42 billion in the month. The ISM services index for August is also released on Thursday together with the Challenger series on job layoffs. The regular weekly data on claims for unemployment insurance is also issued.

And on Friday, the highlight of the week arrives. The August jobs market data is released with most focus on employment – the non-farm payrolls series. The job market has improved markedly over time with job growth now consistently above 200,000 every month. And the jobless rate stands at 5.3 per cent. Economists tip job growth of 215,000 for August and unemployment at 5.2 per cent.

The jobs data is pivotal to the debate on when the Federal Reserve starts the rates “normalisation” process. That is, the time when the Fed lifts rates from zero. But for the Fed to be confident about lifting rates in September, members don't just want to see job growth and lower unemployment but also evidence of inflation in the form of rising wages.

Sharemarket, interest rates, currencies & commodities

When investors are selling off assets across the globe, they don't tend to differentiate much. Chinese shares were well over-priced on traditional price-earnings calculation. They still are. And both US and European markets were also 15-20 per cent over-valued – ripe for picking if enough in the way of “bad” news comes around. As it does. Before the recent global sell-off the forward PE ratio in Australia had lifted to 16.6, about 10 per cent above the long-term average near 15.