Kohler's Week: US payrolls, Recession, China, Commodity bust, Dividends, Lithium, IPH

Last Night

Dow Jones, down 1.67%

S&P500, down 1.54%

Nasdaq, down 1.05%

Aust dollar, US69.1c

US Payrolls

This morning's US payrolls report for August was inconclusive, and leaves the US Federal Reserve's September interest rate decision wide open. The 173,000 increase in employment was less than expected; the fall in the unemployment rate from 5.3 to 5.1 per cent – the lowest since 2008 – was more than expected. Further on the plus were average hourly earnings, up 0.3 per cent (more than expected) and hours worked increased a fair bit as well.

Markets were looking for some decisive data that would tip things one way or the other, but didn't really get it. Reading all the reactions this morning, I guess that, if anything, the report leans towards “hike”, but only just. An analyst named Guy LeBas of Janney Montgomery Scott, quoted in the Wall Street Journal, summed it up: “The reality is that a September rate hike is basically a coin-flip event, and we believe the Fed will settle that flip by calling ‘edge'. In this case, that means a 10 to 15 basis point micro hike.”

Will there be a recession here?

We saw on Wednesday that GDP growth is stuck at 2 per cent, but that's in line with Reserve Bank forecasts so there won't be any cut in interest rates in response to that. If the RBA was uncomfortable with 2 per cent growth, it would have cut already, since that has been its forecast.

At 0.2 per cent for the quarter, the GDP increase was pretty close to zero, so the question arises, and is being asked increasingly wherever I go these days, will we have a recession? That is, will the growth rate of GDP slip below zero for two quarters in a row?

Probably, but that's not necessarily a dire prediction. As it is, the only reason there was a positive number in the June quarter seems to have been the launch and delivery of a new destroyer by the ACS shipyard in Adelaide, which is hardly broad-based economic growth. Moreover, the main reason growth is so weak is the big decline in business investment, which is mainly due, in turn, to the end of the mining boom. Housing and consumption are generally OK, and although retail sales unexpectedly fell this week, that was mainly due to a give back of the big rise in June due to the tax break for small businesses.

In my view a shallow recession is looking increasingly likely, and if that's what it is – no big deal. Unemployment might go to 7 per cent, but not necessarily to the 8-9 per cent that would cause the banks a lot of problems with loan impairments, since the mining industry employs so few people (2 per cent directly and less than 10 per cent indirectly). And the RBA would definitely cut rates again, which would give another leg to the housing boom.

The big danger of a recession is that it might remove the last vestiges of the Coalition's standing as economic managers and sap the Government's confidence to do anything at all, at the same time as destroying business confidence.

Against that, it's just possible that a recession would galvanise the Government into action by giving it the excuse to trample over the vested interests that seem to be paralysing it at the moment and preventing reform. In 1986, five years after the recession, reform was stalling, so Paul Keating got on the blower to John Laws and warned that we faced becoming a banana republic if we didn't get moving on more reform. That worked.

It's not entirely clear whether Tony Abbott and Joe Hockey actually want to be reforming leaders, and are simply bogged down arguing with political minders, bureaucrats and lobbyists. It's possible they don't have it in them, but if they do, a recession could clear a path through the naysayers around them. Mind you, it's a pity we have to be talking like that at all – wishing for a recession to get something happening.

Banks in a recession

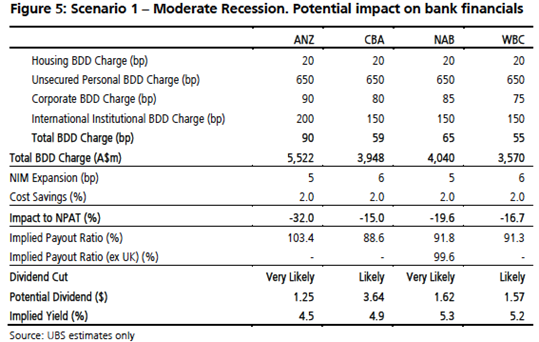

There's been quite a lot of attention this week on a piece of work by UBS banking analyst Jonathan Mott, looking at the impact of a recession on the banks, and in particular on their dividends.

Scenario no.1 assumes continuing slow growth of 1-2 per cent, unemployment rises to 7 per cent and house prices are flat to 5 per cent down. In this scenario, CBA, NAB and Westpac are “unlikely" to cut the dividend, while ANZ is “possible”.

Scenario no. 2 “assumes the Australian economy endures two-to-three consecutive quarters of negative growth, with the Asian economies suffering from a harder landing.

“GDP is assumed to grow only 0-1 per cent and the unemployment rate is assumed to rise to around 8.5 per cent. We assume the RBA would cut rates to 1 per cent. Western Australia and Queensland are assumed to suffer harshly from this slowdown, while NSW and Victoria also enter a mild downturn. In New Zealand, the Auckland economy slows sharply, while the dairy and rural sectors suffer a more severe slowdown. House prices nationally are assumed to fall 10-15 per cent, with larger falls assumed in Perth and regional areas.”

Here's his table of the impact of this sort of “moderate” recession on bank financials:

I thought you'd like to know.

China oh China

It would have been with some relief that Xi Jinping lined up with his comrades and cadres to salute the Victory Day parade through Beijing on Thursday. “This is more my scene”, he would have been thinking as the troops goose-stepped past, perfectly drilled, interspersed with large phallic missiles.

The past few months of dealing with the very imperfectly drilled markets in equities, foreign exchange and money have been stressful and unsuccessful, all things considered. China has gone from being the triumphant engine of global growth – “stronger for longer” used to be the description that the capitalists in New York and Sydney used – to being the leading cause of distress, both to the world and to the Chinese leadership.

China has taken over from the US Federal Reserve as the key influence on global markets for two reasons: first “stronger for longer” has had to be restated as “not so strong for not quite as long as we thought”, and second, and perhaps more importantly, the Government's commitment to structural reform of the economy – letting market forces have their way – has apparently fallen at the first hurdle.

Not that intervention in markets is somehow unique to communist states (to wit QE and zero interest rates), but China's attempt to prop up the stock market, including the arrest and incarceration of short sellers, smacks a little of desperation – and failed desperation at that. Also, the devaluation of the yuan, small as it was, is still reverberating. The renminbi was going to be the new concrete foundation of the international monetary system, anchored by China's uniquely stable system of government – Socialism With Chinese Characteristics, as the official ideology of the Communist Party has it.

And it's true that since that slogan was adopted in 1978, more than 500 million people have been pulled out of poverty, and its cheap manufactured products and demand for raw materials transformed the world. This year it was going to move to the next phase of international acceptance, the Chinese currency incorporated in the IMF's Special Drawing Rights basket and to list their shares in the MSCI global indices. But both aspirations have ended in failure and fiasco, with a stock market crash and a devaluation.

Markets are now having to rethink China, and don't quite know where to land. Volatility is the natural result.

The essence of the problem is that the Chinese central bank must try to pull off what is sometimes called the “impossible trinity” – a stable exchange rate, an open capital account and an independent interest rate policy. The Australian Government gave up on this in December 1983, allowing the currency to rise and fall and capital to come and go, so that interest rates could be set independently of the Federal Reserve.

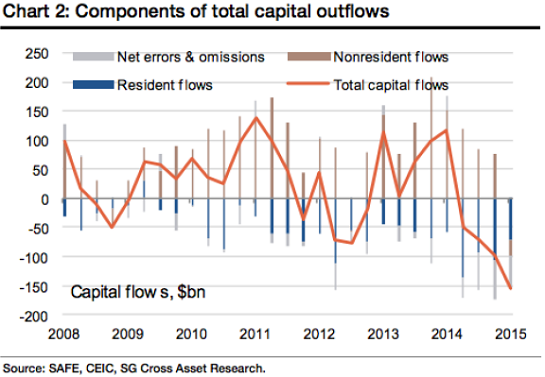

China has been liberalising its capital account for five years but has kept full control of both the exchange rate and interest rates. The pressure boiled over on August 11 when the yuan was devalued and the trading band widened, but since then the PBoC has tried to keep the currency stable. This has led to another $150 billion depletion of its already depleted foreign exchange reserves. In order to maintain a stable exchange rate now, the PBoC will be in a continuing war of attrition against capital outflows, much of which is private, such as the money coming into Australian real estate.

(Note that the second biggest component of capital outflows is “net errors & omissions” – in other words, goodness knows whose money it is.)

In this environment of capital haemorrhage even China's colossal FX reserves of $US3.5 trillion (down from $US4 trillion) will quickly drain away, and the problem is that selling dollars and buying yuan to hold it up has the side effect of tightening domestic monetary conditions, leading to further economic weakness and further capital outflow.

So while the PBoC has said it has no intention of letting the yuan fall much further, no one thinks it can hold out for very long. Most forecasts have the yuan significantly lower in a year's time (along with the Australian dollar).

Clearly the most important issue for us is the slowing Chinese economy, not so much the central bank's struggles with the forex markets. With that there is double trouble: not only is it slowing, but investors don't have confidence in the data. No one thinks the growth rate is still 7 per cent, but no one knows whether it's 6 per cent, 5 per cent or less.

Also there is a massive debt overhang in China, worse than almost anywhere else. Overall debt is now 280 per cent of GDP.

The PBoC is acting aggressively to boost the economy with looser monetary policy – cutting interest rates as well as the reserve requirement ratio. But it's not called “the impossible trinity” for nothing: it is impossible to cut interest rates to maintain economic growth while holding the currency up and preventing capital outflows. Can't be done.

UBS's China macro team put out a note this week saying they expected the Government to stabilise economic growth at 6.5 per cent by doing “whatever it takes” à la Mario Draghi, but they acknowledged that risks are to the downside.

Meanwhile the share market there remains disconnected from the real economy and could do anything at all.

Source: UBS

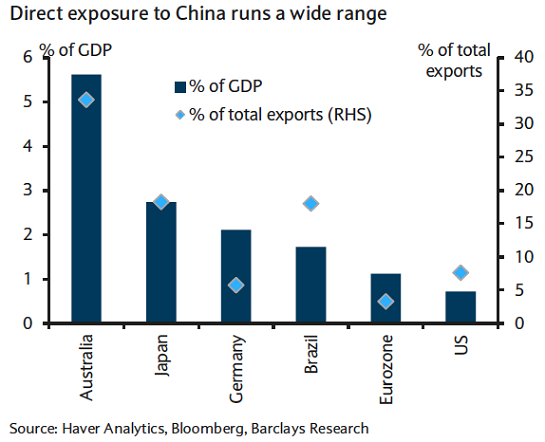

And finally, in case you were wondering how much this matters to us, in addition to the indirect effect through global market volatility, China is more important directly to Australia than almost any other country:

The commodity bust

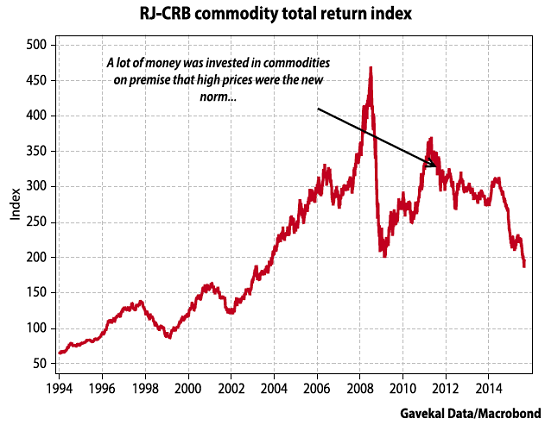

Having said all that, I don't think there'll be a China crash, although the chances of it are greater than zero. However the commodity bubble and bust that is a direct consequence of China is clearly the most important economic fact for all Australians, and especially investors.

The problem is that between 2009 and 2011 there was a false rally that lead to entirely the wrong conclusion.

Money poured into commodities, and resources stocks, on several false premises:

1. That China was, after all, impregnable.

2. That the world would run out of most commodities, so that supply shortages would make them a one-way bet

3. That investing in commodities would be a hedge against the inflation that would inevitably come from QE and zero interest rates.

Well, inflation didn't arrive, and doesn't look like it will, supplies of virtually everything have boomed and China is definitely pregnable (Is that a word? – ed).

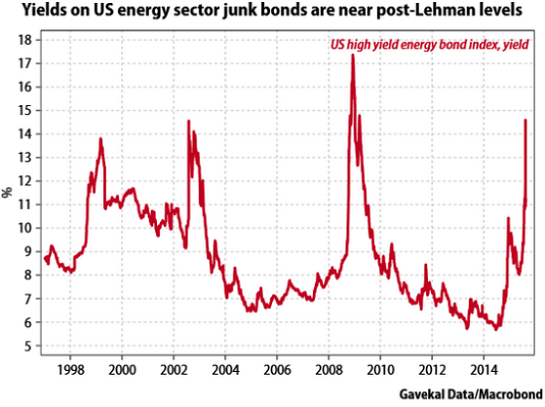

Most previous commodity busts in the past have resulted in not just capacity shutdowns and cost retrenchments by producers, but also a phase of bankruptcies. Markets are starting to worry that this time around the losses will again be borne by debt holders as well as share holders, as shown by this chart of energy sector bond yields.

In dividends we trust

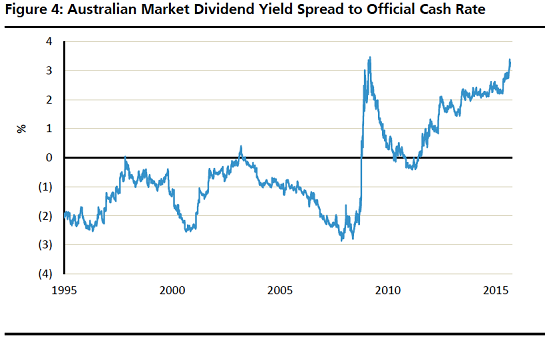

One of Australia's best investment strategists, David Cassidy of UBS, put out a report on the local market this week assessing where we stand after the correction and concluded that:

1. The dividend yield should now support the market, but

2. It's questionable how much dividends can grow from here.

Following the 15 per cent correction from the April highs, the average dividend yield of 5.3 per cent is at close to a historic high versus the cash rate:

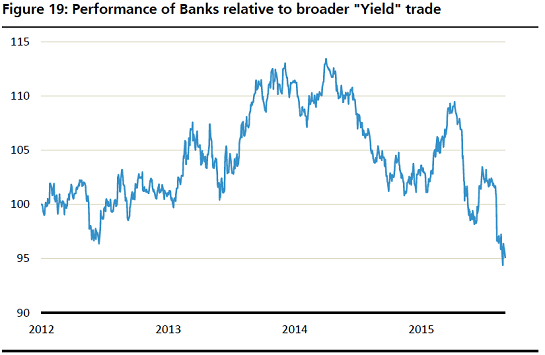

However, he makes the point that the banks have underperformed other yield stocks because of the headwinds caused by their capital raising needs.

The Australian market's two biggest sectors, and the twin foundations of most portfolios – banks and resources – have been the worst performing sectors this year – down 11 and 17 per cent respectively, year to date, versus 7 per cent for the ASX 200 (including banks and resources).

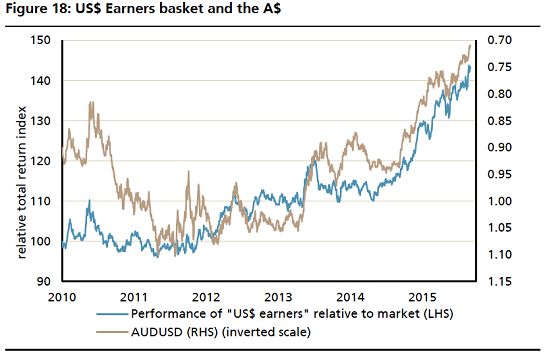

This is likely to continue for some time yet because the Australian dollar is likely to depreciate further. The currency fall has little or no impact on the banks and is offset for the mining and energy stocks by the even greater declines in the prices of their products.

If you think, as I do, that the Australian dollar has quite a bit further to fall, then you would look to be overweight Australian industrial US dollar earners, which excludes banks, but includes Clay Carter's picks of the best US listed stocks.

Lithium

One commodity that is perhaps in a different class to the others is the lightest metal – lithium.

It has long been used as an anti-depressant but since researchers at Oxford University showed in 1979 that it could also be used as one of the electrodes in a rechargeable battery, it has moved from being a pharmaceutical to a commodity.

iPods (2001) and iPhones (2007) rapidly expanded the demand for lithium, although in each case the batteries are very small, and shrinking, so demand was limited. Then Tesla came along with the all-electric car which required much bigger batteries, so that demand took another step up, and then a few months ago Tesla's Elon Musk launched a revolution of the electricity industry with low-priced, mass produced batteries for the storage of solar power.

UBS's energy analysts produced a report in June that said: “We believe the market underestimates the magnitude (1/4 of global installed base by 2050E vs 4 per cent today) and the implications of the looming solar revolution…”

In some parts of the world, UBS said, solar is already cheaper than thermal coal generation, and is becoming cheaper all the time:

"Our analysis shows a c50 per cent decline in new entrant levels, to €55/MWh by 2025. By then solar would no longer need subsidies. In sunnier regions, solar is already competitive today. Although solar capacity brings externalities (backup needs, further investments in smart grids/storage), we would stress that (i) solar also brings major advantages such as energy independence, and lower emissions; and (ii) the cost curve implies that solar will be a viable choice, even once accounted for such externalities; (iii) investments in smart grids and storage will have a positive cost-to-benefit impact on consumers, over the longer run (savings on opex/maintenance capex and on consumption).”

Countries that don't have well-developed power grids, such as in Africa and parts of Asia, won't need them. A cheap solar panel and battery will give third world countries power for lighting, heating and communications. And by the way, the camping shop, Ray's Outdoors, has 200W solar panels for $599 – a friend told me that if you go to camping sites these days you see grey nomads sitting outside their caravans surrounded by solar panels.

On the subject of batteries, UBS says: “The intermittency in the supply will require an upgrade in the power distribution network; we estimate €0.3trn capex by 2025 and up to €3trn by 2050. We also expect a major boom in batteries (both grid-scale as well as residential): the IEA forecasts half a trillion capex to 2050.”

My main interview this week is with Chris Reed, the managing director of Neometals, the Perth-based owner of a lithium deposit in WA. The company has just signed a “life of mine” take or pay contract with China's second largest lithium producer, Jiangxi Ganfeng Lithium Co, and Ganfeng, as it's called, has also bought 25 per cent of the 70 per cent owned subsidiary of Neometals that is developing the mine, and has a call option to take it to 43.1 per cent eventually, which would leave Neometals with 13.8 per cent.

You can watch/read the interview here.

IPH

Simon Dumaresq interviewed David Griffith, the CEO of IPH, the very interesting intellectual property firm. You can see the interview here (sorry – I don't know much about it because I wasn't there – had to go home and cook dinner for my poor sick wife).

Readings & Viewings

I don't really know who Kanye West is, but apparently he's someone important and this week he announced he would run for President of the US in 2020 and it was a big deal. Here is Howard Stern going off about it – he expressed what I think about this.

Australia shouldn't get “too hysterical” about the China slowdown, advises Paul Krugman, who's in town at the moment.

Allan Fels gets stuck into big business over their opposition to an effects test in the competition law, and has a swipe at the Abbott Government for a “disastrous incapacity” to deliver reform.

I found this piece on Catherine the Great of Russia quite interesting.

Economic inequality is not immoral, says this guy.

Bernie Sanders' repeated, exaggerated claims on wealth inequality.

Nice trick: how to perfectly peel a watermelon.

Three simple rules to invest by.

Czech Republic abandons “ineffective” European asylum rules.

Australia and the war in Syria.

The New York Times had an editorial this week headed: Australia's Brutal Treatment of Migrants. Here it is.

Jerry Seinfeld's family's lemonade stand was shut down this week.

Oliver Sacks' first big essay (called The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat) - published in the London Review of Books.

Oliver Sacks' last essay.

Why Oliver Sacks was so remarkable, in six quotes.

Google's new logo isn't just about looks – it's about the future of the internet.

Countries that are dependent on China's growth may have to reinvent their economies.

Four questions and answers about China's economy.

Five things you need to know about Xi Jinping (video).

Why the commodity super cycle was a myth.

Super should be for retirement, not home ownership.

This was an interesting piece with historian Antony Beevor, by Mark Colvin on PM, about the “what ifs” of 1945.

The past, present and future of economics, according to Olivier Blanchard of the IMF.

The man with the world's longest penis says it destroyed his life.

The battle to be the world's most innovative restaurant.

Michael Wolff: maybe Murdoch should sue Google.

The Ashley Madison hack explained.

Cheap oil and global growth.

Looking for a commodity that's rising? Try pollution permits.

Are you good enough to be a tennis line court judge?

This artist's reworking of a picture that went around the world this week doesn't need words:

Last Week

By Shane Oliver, AMP

Investment markets and key developments over the past week

While shares managed to remain above recent lows they had a volatile week with most markets falling back over the week thanks largely to ongoing worries about Chinese economic growth and the Fed, but indications from the ECB that it is prepared to ease further if needed - “the Draghi put” - providing support. Despite share market weakness and a slight rise in the US dollar, commodity prices rose from oversold levels but this didn't help the Australian dollar which fell below $US0.69 for the first time since 2009. Bond yields mostly declined as deflation fears and safe haven demand remain.

Our assessment remains that the next few months are likely to remain rough for shares as September and October are often tough months and the worries about China and the Fed are likely to linger for a while. As a result, it's still too early to be confident we have seen the low.

Beyond the uncertain near term environment I expect to see the usual December quarter seasonal strength helped along by much improved valuations, increasing confidence that China has got its growth under control and investors getting more comfortable that the Fed is not going to do anything to upset US/global economic growth.

One thing that will ultimately help the Australian economy and share market is the continuing plunge in the value of the Australian dollar. When it comes to currency forecasting J.K Galbraith's observation that “there are two kinds of forecasters: those who don't know, and those who don't know they don't know” is particularly pertinent. So I have to be humble and admit that I don't have a clue how low the Australian dollar will ultimately go. But my analysis indicates that - in the context of commodities being in a long term downtrend, the Australian economy struggling and the interest rate gap in favour of Australia likely to narrow further - the Australian dollar has a lot more downside. Having broken below $US0.70, the Australian dollar is expected to fall to $US0.60 in the next year or so, and possibly fall even further.

The plunging Australian dollar – which is now down 37 per cent against the US dollar since its 2011 high - is certainly bad news if you are planning an overseas holiday or if you do a lot of purchases online at offshore websites, but that's the point. Its forcing Australian's to think about holidaying more in Australia, its helping drive a return in foreign tourists and foreign students to our universities and its turning Australians off their love affair with shopping overseas which is good for our retailers. Manufacturers who survived the high Australian dollar years will likely now survive and hopefully prosper and farmers and miners will get a benefit when their US dollar earnings are translated back into Australian dollars. And at the same time it's not exactly causing a surge in imported inflation. So on balance a lower Australian dollar is just what Australia needs right now to help rebalance the economy in the face of the mining downturn.

Major global economic events and implications

US economic data was mixed with a fall in the much watched ISM manufacturing conditions index for August and slightly softer than expected labour market indicators but stronger than expected construction spending and vehicle sales, continued strong readings for the ISM services conditions index and a narrowing in the trade deficit for July. The Fed's Beige Book of anecdotal evidence indicated “modest to moderate growth” with “slight to moderate” wages pressure and “stable” prices. Cutting through the volatility the US economy looks to be continuing to grow somewhere around 2-2.5 per cent, which is good but a long way from booming.

As expected the ECB left monetary policy unchanged at its meeting, but in response to downwards revisions to growth and inflation forecasts and global uncertainties has adopted a strong easing bias with a “willingness, readiness and capacity to act”, suggesting that if the downside risks don't recede soon an expanded quantitative easing program could be announced before the end of the year. Eurozone inflation was a touch stronger but still well below target providing plenty of motivation for the ECB to do more if global risks increase. The good news though is that despite all the uncertainty lately the Eurozone composite business conditions PMI for August was actually revised up to its highest level for this recovery.

China's business conditions PMI's added to concerns about Chinese economic growth with the official manufacturing PMI down slightly in August and services PMIs also down. The falls were not dramatic and in normal times would not have had a huge impact but with so much interest in China now they served to rattle global share markets again. Meanwhile, the risks of a property crash – last year's big China worry – continue to recede with home prices up in August for the fourth month in a row led by Tier 1 cities.

Australian economic events and implications

In Australia the good news was that GDP growth did not have a feared dip into negative territory in the June quarter. The bad news was that at just 0.2 per cent quarter on quarter it came pretty close and only avoided it thanks to a surge in public spending. With detractions from trade and inventories unlikely to be repeated in the current quarter growth should bounce back a bit but only to around the average pace of the last year of 0.5 per cent qoq or 2 per cent year on year as the slump in mining investment continues to unfold. July/August data so far provide a rather messy read: the trade balance improved in July; building approvals remain strong but increasingly look to have peaked; and July retail sales fell. Manufacturing and services PMIs both rose in August to solid levels but then again there have been a few temporary spikes in these PMIs over the last few years. The overall impression is that annual growth looks like it will be stuck around 2 per cent for some time. With this being well below potential (even if potential is now just 2.75 per cent) spare capacity evident in rising unemployment will continue to build. So the economy is likely to need more help.

With fiscal stimulus seemingly ruled out due to the focus on budget repair and with seemingly little appetite for serious economic reforms the pressure will fall back on the RBA to cut rates further and on the Australian dollar to continue to slide. Low inflation pressures according to the TD Securities Inflation Gauge and possible signs that APRA's measures to cool property investors are showing up in slowing home price gains suggest that the RBA will have the flexibility it needs to move again. While the RBA's post September meeting statement indicated it was comfortably on hold for now, it's expected to resume easing by year end – with the November meeting being the one to watch – or early next year.

Next Week

By Craig James, Commsec

Employment dominates domestic data

After the tsunami of economic data over the past week, another round of top-tier economic indicators is expected in the coming week. In fact, at least another six economic indicators are due for release in Australia. In the US, the key economic data isn't released until late in the week. And in China key economic data is released on Tuesday, Thursday and Friday, covering trade, inflation, production, investment and retail sales.

In Australia, the week kicks off on Monday with job advertisements. To some degree the job advertisement figures have lost some of its linkages as a leading indicator of employment. More jobs are now posted on individual company websites, social media such as LinkedIn, Facebook and even Twitter, and job placement agencies. But the job ads data is still important in watching for turning points. In that context there have been encouraging signs with a sustainable lift in business hiring intentions. Jobs ads are up almost 11 per cent on a year ago.

On Tuesday the National Australia Bank business survey is released. The business survey covers key business indicators, a reading on business confidence as well as gauges on prices, wages and finance. The indicators of confidence and conditions have showed encouraging improvement since the Budget, with a particular focus on a lift in profitability.

On Tuesday Reserve Bank Head of Financial Stability, Luci Ellis, delivers a talk on the property market. And on Wednesday both the Reserve Bank Deputy Governor Philip Lowe and Assistant Governor Guy Debelle deliver speeches.

On Wednesday two indicators of note are released: The monthly Westpac/Melbourne Institute consumer confidence survey is released alongside housing finance data. The volatility in global share markets may have affected confidence levels. But for the most part the monthly confidence reading should mirror the more timely weekly survey released each Tuesday by ANZ/Roy Morgan.

The housing finance data are new commitments made by lenders for the purchase or building of homes and renovations. We expect that the number of loans made to owner-occupiers (those who want to live in the homes) rose by 1.5 per cent in July. Clearly housing remains the growth driver for the broader economy.

On Thursday the ABS releases the monthly employment figures. Overall we expect that the number of jobs rose by around 10,000 in August, while the participation rate may have eased from 65.1 per cent to 64.9 per cent. As a result we expect that unemployment eased from the headline grabbing 6.3 per cent to 6.1 per cent.

Closing out the week on Friday, the Bureau of Statistics will release lending finance figures – includes housing, personal, business and lease loans. The June lending statistics show a mild rebound in June, largely driven by the strength in housing finance and in that context it is investor housing in particular that has driven the strength. Overall lending is only just shy of the seven-year highs reached two months ago.

Overseas: Chinese economic data in focus

In the US, the week kicks off on Tuesday with consumer credit figures, the NFIB small business index and employment trends index. Economists expect that consumers continue to warm to low borrowing costs with credit tipped to have expanded by US$18 billion in July after a lift of US$20.7 billion increase in June.

On Wednesday the usual weekly data on mortgage finance commitments is released with the JOLTS job openings index.

On Thursday wholesale inventories and sales data for July is released together with import and export price data. Economists expect that both wholesale sales and inventories expanded by 0.3 per cent in July. Also on Thursday the weekly data on claims for unemployment insurance is issued.

Investor interest levels should pick up on Friday. Not only will producer price data be released, but also the preliminary reading on consumer sentiment. Producer prices or business inflation is expected to have contracted by 0.1 per cent in August. Stripping out volatile items like food and energy prices may have risen by around 0.1 per cent. Overall inflation remains well contained, and if the current sharemarket volatility dampens sentiment, the Federal Reserve certainly has time on its hand before needing to lift interest rates.

In China, the week kicks off on Tuesday when China releases its exports and imports data. Economists expect that exports fell at a 5 per cent annual rate in August, while imports are tipped to slide by 6 per cent. Overall the trade surplus is expected to have lifted from $43 billion to $51.1 billion in August.

On Thursday China's National Bureau of Statistics issues inflation data for August – both consumer and producer prices. Inflation is well contained at present with producer prices still falling, not rising. Economists expect that producer prices fell 5.5 per cent over the year to August while consumer prices grew 1.9 per cent over the period.

On Sunday the monthly batch of Chinese economic indicators are released – retail sales, production and investment. There are signs that Chinese economic activity is gaining pace and investors would want to see further confirmation of that trend. Expect annual retail sales growth near 10.6 per cent with production near 6.3 per cent and investment near 11.2 per cent. The risk is that the results print on the weaker side of expectations – especially given that China closed down heavy manufacturers and restricted transport in Beijing due to the World Athletic championships. We would expect activity levels to lift in coming months.