Kohler's Week: Disruption special

Last Night

Dow Jones, up ~0.4%

S&P 500, up ~0.3%

Nasdaq, up ~0.5%

Aust dollar, US72.4c

Strong dollars

Both the Australian and US dollars were strong overnight. The greenback rallied against the euro because of twin central bank comments: the European Central Bank's Mario Draghi added some weight to the idea that there will be an easing of monetary policy in Europe next month and the head of the New York Fed, William Dudley, said the main Federal Reserve will be ready to raise interest rates “soon”.

But even though the US dollar rose quite strongly, both against the euro and its index, the Aussie went up as well – from below US72c to US72.4c as I write this morning. It started the week at US71c, dipped to US70.8c but has finished strongly.

I wrote here recently that you shouldn't expect the inevitable result of a rate hike in the US to be a higher US dollar and lower Aussie. It looks like I was wrong about the first of those and right about the second. Both dollars are rising – which implies that the Aussie is stronger than the greenback – which is a bit hard to fathom, but that's what is happening. Both dollars have rallied all week, even though commodities are weaker and the Fed has more or less confirmed that US rates are going up next month.

I can only assume it's the tailwind of the powerful increase in Australian employment last Thursday that's whipping the Aussie higher, because of forex punters lowering the odds of another rate cut here. There's certainly nothing in the commodity markets and China yet to suggest a reason to buy Aussie dollars.

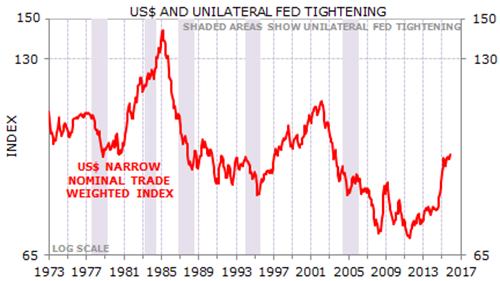

As for the US dollar, it has mostly been a “buy the rumour, sell the fact” trade when the Fed unilaterally raises rates, as this graph from Gerard Minack (sort of) demonstrates:

It's not all that conclusive, but there's definitely no pattern of a US dollar rally during and after a unilateral Fed hike, which is what is going to happen (probably) next month.

Disruption, Part 1

I wrote a 1000-word piece for this morning's Australian that I headed: “The six great disruptions (the greatest is trust)”, although they might have changed the heading (they usually do). I want to use it as the basis for a discussion of the big business and investment issues around the theme because I think it is easily the most important thing facing us all at the moment.

But first you need to read the article, and for those of you who don't subscribe to The Australian or Business Spectator, here it is in full:

“The day after a book called “The Rise of the Robots” won the Financial Times and McKinsey Business Book of the Year award in London this week, a little company called Fastbrick Robotics listed on the ASX and promptly doubled in value.

It was instant fulfillment. Fastbrick Robotics has invented a bricklaying robot; the book, by Silicon Valley entrepreneur Martin Ford, presents a grim view of a future in which robots permanently replace human jobs.

Replacing brickies with robots is not that surprising when you think about it -- after all, laying bricks is a repetitive, robot-like task. Talk to me when you've invented a robot builder, then I'll be impressed (and grateful).

Brickies might not agree, but the corporate videos of Fastbrick Robotics present a bright new world of quick and efficient construction, in which a house can go up in two days.

“The Rise of the Robots”, on the other hand, foresees a dark dystopian future of fewer jobs, with disruption from machines and algorithms on both manufacturing and professional industries.

According to the reviews (I haven't read the book yet), Ford essentially argues that the current industrial revolution will not be like the last one, when new jobs were created just as quickly as the old ones were eliminated by technology.

He writes: “While human-machine collaboration jobs will certainly exist, they seem likely to be relatively few in number and often shortlived. In a great many cases, they may also be unrewarding and even dehumanising.”

According to Martin Ford, artificial intelligence is already well on its way to making “good jobs” obsolete: many paralegals, journalists, office workers and even computer programmers are poised to be replaced by robots and smart software. As progress continues, blue and white collar jobs alike will evaporate, squeezing working and middle-class families ever further.

But Ford does not only talk about job theft by machines. One of his key points is that robots weaken middle-class demand by skewing the gains to a few – worsening inequality.

As labour becomes uneconomic relative to machines, purchasing power falls. For example, the US economy produces a third more today than it did in 1998 with the same sized workforce.

What he doesn't mention is that macro-economic policy is doing the same thing, to some extent driven by digital disruption and robotics.

Just as falling wage growth is reducing middle-class demand, so are super low interest rates. It's true that disposable incomes of middle-class mortgagees are being boosted by low interest rates, but that is being cancelled by the opposite effect on retirees who live off their savings.

To some extent it's a circular phenomenon: automation and disruption reduce costs and prices, reducing inflation and therefore interest rates.

So monetary policy itself becomes a disruptor. Not only is wage growth the lowest on record and have unit labour costs not grown at all for three years, interest rates are the lowest they have ever been. In the US they have been effectively zero for seven years.

As I see it the world has to deal with six great disruptions at once:

1. Monetary policy

Zero interest rates and quantitative easing are one of great disruptive innovations of our time: negative real interest rates – and in some places even negative nominal interest rates – and central banks simply printing money and buying assets from banks. It's an experiment that is having a profound effect on the way all markets and economies operate.

2. Computing power

When Gordon Moore observed in 1965 that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit could double every year (and then revised that to every two years in 1975) it was early days for Moore's Law. Forty years of that exponential growth in computing power is now affecting every part of life. Moore's Law is responsible for smartphones, robotics, artificial intelligence, programmatic trading in shares and advertising … the list goes on, and includes all the things that Martin Ford is so worried about.

3. Cloud computing

In a way this is an extension of Moore's Law, but turning both data storage and software into a service – operating expenditure rather than capital expenditure – is itself hugely disruptive and deserves its own mention.

4. Hyper-Connectivity

In an interview this week with Stephen Bartholomeusz and myself for Business Spectator, the CEO of Telstra, Andy Penn, revealed that the company had achieved a data speed over its mobile network of one gigabit per second in a test environment. Similar download speeds are already being achieved over fixed line. This has meant the internet can be used for broadcasting as well as connecting millions of machines (the “internet of things”) transmitting colossal amounts of data and storing it in the cloud.

5. Blockchain

This is the technology at the heart of Bitcoin, but its uses go far wider than that. Blockchain is a way of organising and verifying almost any transaction. It is early days, but already clear that this technology will eventually be at the heart of a new banking system and a new settlement system.

6. Trust

In my view this is the most powerful disruptive force of all. The internet has become a tool for humans to deal directly with each other. And it turns out that in even a world that is also being disrupted by appalling acts of terrorism, there is an overwhelming urge for people to trust each other.

We go and stay in each other's houses (Airbnb), get in each other's cars (Uber), buy stuff from each other and pay first (eBay etc). We tell each other about our lives and ideas (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram etc) and we're now lending each other money (SocietyOne, Lending Club etc).

The willingness of humans to trust each other and, separately, to express themselves to each other, is not a new thing, but the internet has unleashed it and allowed it to be organised.

The social urge in human society has always existed, but has been confined to small communities simply because of the lack of any means to communicate efficiently across large distances.

The combination of connectivity and computing power has literally put that ability into our pockets – it's with us everywhere we go. It has meant that our inherent urge to trust and communicate can be both fully expressed and organised.”

Disruption, Part 2

I've banged on enough in this place about monetary policy and the disruptive role of central banks since the GFC (with which not everyone agrees, it must be acknowledged), so I'll leave it at that for today. Today I want to focus on three other things: the challenges for large companies, the disruptive power of trust, and how to win from the new industrial revolution.

1. Big and Little

Two quotes to start with:

David Craig, chief financial officer of Commonwealth Bank this week: “…we have an incredible responsibility to keep everything stable. If our banking system goes down for five minutes it has an enormously disruptive effect on the Australian economy.”

Andy Penn, CEO of Telstra, from our interview with him: “I feel a weight of responsibility for our shareholders, for our customers, for all of our people. I mean it's not one though that keeps me awake at night, it's one that excites me. But I want to say that I feel the weight of that responsibility because I don't want anyone to think that I take this lightly. This is a really important organisation. It … features probably in every individual superannuation savings in Australia, either directly or indirectly. Basically it's the core backbone of the communication infrastructure in Australia which sits behind the whole economy and we represent, you know, tens of thousands of people's careers, so it's a really responsible job.”

Here's something else that Andy said: “You know, in many ways, (start-ups and entrepreneurial businesses) are more disciplined than large complex organisations. In a sense, you know, these start-ups … which are sort of raising capital for the next 12 months and then they've got to work out where they're going to get the capital from next time, they've got very, very clear sets of KPIs and objectives and deliverables. They may not be sales and profit, they may be around customer acquisition, product development, but they have very, very clear and robust KPIs.”

It seems to me these are important ideas that don't get enough attention. The people running big companies do feel the weight of their responsibilities, to shareholders, staff, customers and in many cases the economy as a whole – what are these days called stakeholders.

It's easy, as I have done, to ridicule big firms for a failure to respond quickly enough to the changing world, and specifically to threats and challenges from digital disruption, but apart from the sheer time it takes to get a large bureaucracy to change course, two questions weigh heavily on the minds of executives: is it the right thing to do, and when is the right time to do it?

In speeches I have described large companies as “anti-mistake factories”, because the staff spend their lives trying not to make mistakes and covering their backsides when they do make one. That's because their boss usually takes credit for their successes but they wear the blame for failures, so there's no percentage in doing anything other than playing up the former and hiding mistakes.

Which is all very well, and perfectly true, but to some extent it's a legitimate part of the 'responsibility' thing. Big company executives and directors are naturally risk averse because so much often rides on what they do – the careers of thousands, the savings of hundreds of thousands, the needs of millions. It's inevitable that they will be more careful than someone with his or her own business and five staff, and so they should be.

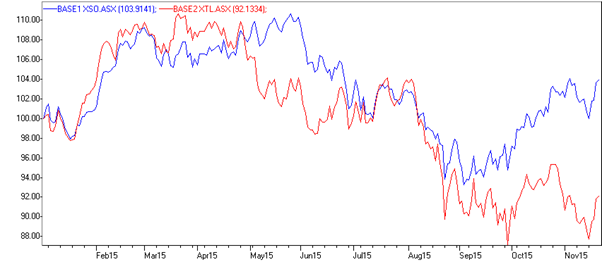

Is that why this has happened?

It's the Small Ordinaries Index and the 20 Leaders this year which I showed on the ABC News on Thursday night. Since late August a big gap in performance has opened up between big and small companies. Obviously it's largely driven by the underperformance of the banks and big miners, which is partly due to concerns about their dividends. But to what extent is it also the uneven impact of disruption on large and small firms?

During the week I received an interesting email on this subject from a local author and organisational consultant, Patrick Hollingsworth, who took the subject a little further:

“Most traditional commercial organisations in which we have grown up investing use an outdated organisational structure that has its origins in the North American railroad boom of the 1850s. This structure is linear, hierarchical and top-down, and they are large and powerful, but also incredibly cumbersome. These large businesses are incredibly invested in the status quo, because it is the status quo that they know so well and which enabled them to become so successful. This traditional linear structure worked when the world was relatively stable and certain. There was enough time for the senior management to make decisions and respond to their surrounding commercial environment. But not anymore. Their size, which was once their greatest strength, is now their greatest vulnerability. Exponential growth in some fields of technology is making these traditional linear organisations obsolete seemingly overnight. So many Australian companies are at risk.

“Notwithstanding my natural bias against most things to do with numbers and analytics, I have always been curious as to why so little attention is given by stock market analysts and the like to the softer ‘people' side of companies. Being based in Western Australia, I used to do a lot of work with large oil and gas and mining companies (not so much anymore!), and reports of the deteriorating workplace culture in some of these organisations as a result of significant cost restructuring are not exaggerated. And while we tend to focus on falling commodity prices, what about the long-term impacts on the culture and workforce of these businesses from these reactive and culture-destroying responses to volatility? Perhaps not in the short term, but in the long term I reckon the impact could be quite significant and will undoubtedly have an impact on these companies' financials (noting that poor workplace culture leads to chronic employee disengagement, and the predicted annual cost to the Australian economy from a disengaged workforce is $50 billion; in the US it's $US500bn). I could go on and on about this, but you get the picture.

“The change that technology is bringing will be unlike anything else that we have experienced before. And I really don't think enough of us are aware of truly how much this technologically driven change is going to alter things. The way we do our work, the way our children get educated, the way we recreate, and generally live our lives is going to change.

“So many organisations right now are stuck in the status quo, thinking it's business as usual, when it isn't. This type of complacent thinking will kill many of the organisations that we once considered to be blue chip and always likely to remain in our portfolios.”

A final note on this subject: a friend of mine runs a business in Sydney called Pollenizer. It began as an incubator for start-ups, but over time has turned into a consultant for big companies, helping to foster a start-up, entrepreneurial culture within them. Most of the time a big client will ask them to help set up a division that can behave like a start-up, but they usually end up having to bring about change in the whole organisation, starting at the top, so the start-up division doesn't get killed. They are being run off their feet, so at least some big firms are seeing the problem.

2. Trust

What I'm calling trust is often referred to as the sharing, or collaborative, economy, except I think it's bigger and more disruptive than that term implies.

A small, left field, example: as far as I can tell (which may not be terribly far) most people these days find partners via online dating. When I was young, we met women at work or at parties, full stop, but dating websites are so much more efficient, reliable and comprehensive (in terms of the range of people to choose from). I'm told that not only is there a huge pool of candidates, you get to assess the person's credentials before meeting them, and the first couple of dates are acknowledged by both sides to be kind of interviews. Sure, some of the romance of a drunken fumble in the kitchen at a party might be lost, but I'll bet the divorce rate falls in future.

And OK, this is not exactly an example of “trust”, but it's part of what you might call “social organisation”, of which trust, or the sharing economy, is a subset.

I do think there is an interesting paradox at the moment: Islamic terrorism seems to be making the world less and less safe and governments are taking more precautions and being less trusting, yet collaboration and sharing, based largely on trust, are boom industries. It was preceded by the sharing of information about our lives, through social media, as well as what internet philosopher Clay Shirky called the “cognitive surplus”. That phrase comes from a book he wrote called “Cognitive Surplus: Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age”, in which he described the new propensity to create and share, rather than simply to consume. It turns out the consumer society of the 1950s and 60s only existed because we didn't have the opportunity to do anything else. Now we do.

So I actually don't think it's a new characteristic of humanity, but was there all along. It's just that the internet has enabled its release.

Perhaps it's why terrorism has become so shocking – because it's so at odds with the modern paradigm of sharing and trust. I remember when the Red Brigades and Baader-Meinhof gangs were operating and terrorism seemed almost normal. Now every incident, like the one in Paris last Saturday morning, is deeply upsetting.

Apart from the disaffected few, the world is rapidly becoming a smaller, more collaborative and, yes, friendlier, place. Suddenly we are communicating with people around the world on social media, staying in their houses when we travel, buying stuff from them and getting them to do work for us on Freelancer.com.

Of course what we read about and see on the media, both traditional and social, is a lot of very unfriendly stuff about terrorism and the dangers of modern life. But then we put the paper down, or turn off the TV, and get on with our lives of trusting more and more people in the “collaborative economy”.

And in my view collaboration and trust is a more powerful force than the lack of it. That shouldn't be taken to mean that I think that “love” will somehow prevail against jihadists (I don't – I think they need to be defeated, in war). I just think the sharing economy has a long way to run, which is why I have invested in a peer-to-peer lender called ThinCats, as well as a social media aggregator called Stackla and a collaborative publishing platform called Cognitives, after Clay Shirky's book.

Which brings me to …

3. Winning

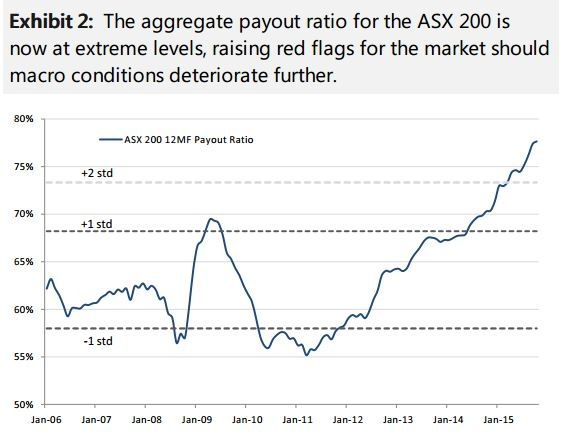

The reason I find this graph so disturbing, apart from the “red flag” mentioned in the heading, is that it means the top 200 companies in Australia are barely investing in the future. My heading on the graph when I put it on the ABC news last week was that Australian companies had become ATMs, which is another way of saying the same thing.

Notwithstanding all Andy Penn's talk about innovation and investment, Telstra paid a dividend of 30.5c out of earnings per share of 34.5c last year. The average bank payout ratio is 75 per cent. BHP, for God's sake, paid a dividend of $1.68 on earnings per share of 46.7c, and is yielding 8.2 per cent! (At least chairman Jac Nasser started softening up shareholders for cut in the dividend at the AGM this week.)

In short, large companies are exacerbating the issues described in the first item today – that is, their cultural and organisational difficulties with disruption – by not retaining earnings for investment.

As a result they have neither the financial nor psychological capacity to deal effectively with the changing world. This is not a blame thing – after all, the pressure on them to maintain high dividend payouts, and therefore to preserve earnings, is enormous – but it's a big problem for them. Meanwhile, most investors are overweight large companies, either by choice because they want the dividends, or because they are in super funds that are, themselves, overweight the ASX top 20, simply because of their position in the index.

If you think I'm working up to suggesting a reduced portfolio weighting to large caps, you're right. I think it's essential for investors – especially those who don't have an immediate need for liquidity – to invest part of their portfolios in a basket of small cap stocks, preferably disruptors. This is hardly a surprising statement from me, but I think it is becoming increasingly important.

Which ones? Well, look, you can't escape the fact that it's your money and your responsibility to find the investments. You can pick from our recommendations, or look at our personal portfolios, or look around for other ideas, or perhaps just choose a couple of good small cap fund managers, like Smallco for example.

But whatever you do, don't just sit in an ASX 200 ETF or index fund and think that you are investing wisely and safely. You're not.

Virgin

I interviewed a busy John Borghetti briefly during the week, on the phone and asked, basically, what's going on? When is Virgin Australia going to perform like Qantas did over the past 12 months (20 per cent versus 200 per cent). His answer, revealingly, was that all other competitors against Qantas, including Ansett, are dead. Virgin is still alive. Didn't really answer the question, did he? But there you have it. Virgin has survived and if it can turn around its international routes from loss to profit, it might even make good money.

Compumedics

I checked in again with the extremely wooly David Burton, the CEO and founder, and 60 per cent shareholder of Compumedics, the sleep and brain pattern diagnostics business. He's an enthusiast, is David (then again, so are all CEOs). But things seem to be going along nicely and the stock has gone from 9c to 30c this year – a handy little 3-bagger for those who have stuck with it. David is pretty convincing that the best is yet to come, so it's worth a look. You can watch the video and read the transcript here.

Readings & Viewings

For nature lovers: one of the most peaceful pictures of a falcon nesting in a tree that you'll ever see.

Charming video of “greatest dad wins ever” – dads have superhuman reactions sometimes.

Here's a quick video of the bricklaying robot mentioned in the first item today.

Gary Shilling: truth telling on China's economy.

China has a $1.2 trillion Ponzi finance problem.

China's economy shows further signs of fragility.

China's plan for global technology domination by any means necessary.

Debt deflation: China's big macro risk for 2016 (video).

Obviously there has been a huge outpouring of commentary about the Paris attacks last Saturday and ISIS. Here are a few of the things I've read this week that I thought were worth passing on:

Michel Houellebecq: How France's leaders failed its people.

Isis Inc: how oil fuels the jihadi terrorists.

Economies are too tough for Isis to destroy.

Isis has created a new kind of warfare.

The mystery of Isis (a review of two books on the subject).

Why states of emergency and extreme security measures won't stop Isis.

An investigation into the pathology of evil.

Close the borders? That would ruin the EU.

Should we be searching the Koran or should we be looking at what motivates young idealists to die for a cause and why are these ones doing it?

And finally, Jeff Buckley, live at the Bataclan in Paris, singing Hallelujah (audio only).

A 1000-year eye remedy has been found to kill methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus, otherwise known as MRSA.

Interesting paper on the San Francisco Fed's website, about why the current housing boom in the US is different to the last one.

Google is investing in a $50m effort to cure heart disease. Yes, but why?

The US treasury yield premium over the G7 is the widest since 2007.

The greatest invention of all time – was it the flush toilet?

Why the Republicans will win next year's US Presidential election.

Human vocal chords have been grown from scratch (and then put in a dog).

In the Netherlands, a woman was taken to hospital and the cops stayed behind to cook for her kids and do the dishes.

If you're looking for a chart that illustrates a long-term, worldwide industrial slowdown, look no further than Caterpillar's monthly sales figures.

Tony Abbott (who promised no sniping) has not given up, according to Phil Coorey of the AFR, and has a sort of ‘government in exile' going on.

On the other hand, this piece says Turnbull has removed the revolving door.

And this, from Barrie Cassidy, says: Australian politics has entered a new and positive era. Yes, really, it has.

The stealthy capture of democracy by corporate interests needs constantly to be called out.

Happy Birthday to the very interesting Bjork.

And Happy Birthday Rene Magritte.

Note: A few readers have pointed out that the link last week to a sea levels website was actually a pretty dreadful climate denial site. Sorry about that – I didn't check it properly.

We've been examining peer-to-peer lenders closely over the past year. They're of particular interest for retirees searching for yield. Have you lent money on a peer-to-peer lending platform? What did you think of the process -- did it meet your expectations? Write in and let us know for a story we're working on: elizabeth.redman@eurekareport.com.au.

Last Week

By Shane Oliver, AMP

Investment markets and key developments over the past week

Share markets bounced back over the last week helped along by a combination of okay earnings news in the US and greater comfort with the Fed raising interest rates next month after the Fed minutes reiterated that the tightening process would be gradual. Australian shares saw a particularly strong and broad based bounce back after managing to hold above their September lows. With Australian shares offering a 5 per cent plus dividend yields it seems that “yield chasing/bargain hunters” may have returned to the market again. My 5500 target for the ASX 200 by year end is starting to look a bit more achievable. Partly reflecting more comfort around the Fed and the prospect of more easing in Europe, bond yields fell. While commodity prices, notably metals and iron ore remained under downwards pressure, the ascent in the US dollar stalled and the Australian dollar was able to push higher.

Perhaps the big surprise for many over the past week was the short lived and muted reaction to the horrible events in Paris from late the previous week. Looking at past experience though this is not very surprising at all.

First, it's worth recalling that parts of Europe have lived with terrorism in decades past, eg the IRA campaign regarding Northern Ireland, the ETA in Spain, the Red Army Faction in Germany, Red Brigades in Italy, etc. After a while many of these threats came to be seen as the norm.

Secondly, the experience of the last decade or so has highlighted that terrorist attacks on soft targets like buildings and sports venues don't really have much lasting economic impact. So while the 9/11 attacks had a big short term share market impact with US shares falling 12 per cent they had recovered in just over a month, the Bali and Madrid bombings had little impact and the impact on the UK share market of the London bombings of July 2005 was reversed the day after.

So while the terror threat is negative for confidence, it would need to cause more damage to economic infrastructure to have a significant economic impact and hence a more lasting impact on financial markets.

In reality there was nothing really new from the Fed, but markets seem to be getting more relaxed about a December rate hike. The minutes from the Fed's last meeting confirmed that the Fed expects to hike in December but that it is dependent on there being no unanticipated shocks, good news regarding jobs and confidence that inflation will rise. So far so good. They also reiterated that the path to higher rates will be gradual.

That investment markets were able to take the reiteration that a rate hike is likely in December in their stride without a panicky sell off in shares, commodities and emerging currencies is a good sign. Global investors appear to be getting used to the idea of a Fed rate hike next month and may be starting to see it as a sign of strength, not weakness. The key is that Fed rate hikes are conditional on continuing economic improvement and that they will be gradual.

Australian petrol prices falling back to where they should be? Apart from a brief collapse in petrol prices earlier this year, Australian retail petrol prices generally haven't come down anywhere near as much as the 60 per cent plus decline in world oil prices adjusted for the fall in the Australian dollar would suggest. However, petrol prices of around $1.117/litre at some service stations in Sydney and $1.08/litre in parts of Perth in the last few days are getting down to around to where they should be. Low petrol prices are clearly a source of support for consumer spending.

Major global economic events and implications

US data releases over the last week were mostly okay, consistent with growth continuing to run around the 2 per cent pa average seen since the GFC. While manufacturing production rose in October, manufacturing conditions in the New York and Philadelphia regions improved slightly but remain soft into November. Housing starts fell in October but a still strong reading for the NAHB home builders' index and a gain in permits to build homes points to continued strength in housing ahead. Jobless claims also remain very low pointing to ongoing labour market strength. Meanwhile, consumer price inflation rose to 0.2 per cent year on year as expected in October with core inflation unchanged at 1.9 per cent. Hard to get too excited by any of this though.

Japan's economy contracted by 0.2 per cent in the September quarter, marking the fourth technical recession in five years. Consumer spending was positive but business investment was a drag. The “stop go” economy is clearly maintaining pressure on the BoJ for further easing, even though it held steady at its regular meeting in the last week.

It's interesting though that while the Japanese economy continues to bounce in and out of recession some indicators are in very good shape, eg the jobs to applicants ratio is at its highest since 1992, Tokyo's office vacancy rate is down sharply and Japan's GDP deflator is at last in a clear rising trend for the first time since Japan's multi decade malaise set in. So Abenomics has had a positive impact.

China's home prices rose again in October led by Tier 1 cities. While there has been some slowing in momentum in the last few months this is a probably a good thing as a return to another boom bust property cycle would not be good.

Australian economic events and implications

Wages growth in Australia held at a record low of just 2.3 per cent year on year in the September quarter highlighting the lack of inflationary pressure from labour costs. Private wages growth fell to a new record low of 2.1 per cent. Quite clearly the adjustment flowing from the end of the mining boom and associated weak demand in the economy is continuing to show up in weak wages growth. This in turn is helping protect employment and partly explains why jobs growth has been able to come in better than expected despite the slow rate of economic growth. So while weak wages growth is a dampener on its own for consumer spending, it's partly offset by solid jobs growth.

Weak wages growth also means that inflationary pressures coming from the labour market remain weak, reinforcing the RBA's easing bias which is predicated on the outlook for continuing low or benign inflation. The minutes from the last RBA Board meeting didn't really add anything new, but it does seem as if the hurdle to act on its easing bias is quite high at present.

Next Week

By Craig James, CommSec

Business investment grabs local attention

Another busy week is in prospect with the quarterly business investment figures dominating the economic agenda. In China, no key economic data is expected. And in the US, the economic calendar is well populated in the lead up to Thursday's Thanksgiving Day holiday.

In Australia, the week kicks off on Monday with the CommBank Business Sales index, a measure of economy-wide spending.

On Tuesday ANZ and Roy Morgan release the weekly consumer sentiment index. Confidence levels are holding just shy of the best levels of the year, underpinned by a positive outlook for consumer finances.

Also on Tuesday the Reserve Bank Governor delivers a speech at the Australian Business Economists annual dinner. Investors will be looking for any remarks on the housing market, Australian dollar and likelihood of further rate cuts.

On Wednesday, the Australian Bureau of Statistics releases preliminary data on construction spending in the September quarter. The estimates of residential building completions feed into the calculation of economic growth in the quarter. And the commercial and engineering data provides early indications of the following day's business investment figures.

Home building is once again expected to be the key driver of construction growth although it is unlikely to offset the weakness in engineering activity.

Also on Wednesday Reserve Bank Assistant Governor Guy Debelle delivers a speech at the FX Week Europe Conference in London.

On Thursday the ABS releases 'Private Capital Expenditure and Expected Expenditure' --business investment or just business spending. The data is broken up into 'building & structures' and 'equipment' and refers to business spending on longer-lasting assets. However, as the title suggests, the data covers not just actual spending but also planned spending over the next 18 months.

In the June quarter, investment fell by 4 per cent, driven by weakness in spending on buildings and equipment. The slide marked the fourth straight quarterly decline. Unfortunately the weakness continues with spending expected to have eased by 6 per cent in the September quarter.

But probably more important than the September quarter results are the forecasts for investment in the 2015/16 year. In the June quarter the third estimate of investment in 2015/16 came in at $114.8bn, up 9.9 per cent on the second estimate (the biggest increase in the third estimate of investment in five years). If planned investment lifts, especially outside the mining sector, then the Reserve Bank will think harder about the need for another rate cut.

US data dominates in a holiday-shortened week

In the US, the week begins on Monday with the release of the Chicago Federal Reserve National Activity Index, existing home sales and the 'flash' reading on US manufacturing.

On Tuesday, a clutch of key indicators is released: economic growth; home prices; consumer confidence; and the influential regional survey by the Federal Reserve in Richmond.

The preliminary estimate of economic growth should show that US economy grew at a 1.9 per cent annual rate in the September quarter. Consumer confidence probably lifted in November while the Case-Shiller home price measure probably showed annual growth of prices near 5 per cent.

On Wednesday, another significant clutch of economic data releases is expected in a holiday-shortened week. The data includes: personal income/spending; durable goods orders; new home sales; the Federal Housing Finance Agency measure of home prices; and consumer sentiment.

A key measure of business spending, durable goods orders, is expected to have lifted by 1.5 per cent in November but a more modest 0.4 per cent increase is expected if transportation orders are excluded.

And while little change is expected in measures of personal income and spending, new home sales may have lifted by between 7-8 per cent in October after the 11.5 per cent slide in September.

Sharemarkets, interest rates, commodities & currencies

Rewind eight years to late October/early November 2007 and sharemarkets across the globe were at or near record highs. Then followed the Global Financial Crisis, the European Debt Crisis and hesitant economic recoveries across the globe. Predictably sharemarkets spectacularly slumped in response to the GFC. On March 9 2009, the US Dow Jones was at 6,547, down 54 per cent from the October 9 2007 high of 14,164.

But just as spectacularly as it slumped, the Dow Jones spectacularly recovered, lifting to fresh record highs and peaking at 18,351 on May 9, 2015. And despite the pullback in the last few months the Dow Jones is up 167 per cent in the past 6½ years since hitting the March 2009 lows.

Similarly European markets have hit fresh record highs earlier this year with the German Dax now up by 206 per cent since its 2009 lows, while the UK FTSE has lifted by 81 per cent since its 2009 lows.

And while the gains have also been spectacular across Asia, the Australian market has more work to do to return to levels of late 2007. The ASX 200 remains 25 per cent away from the 2007 record highs after lifting too far in the China mining boom. But importantly, given the significance of dividends, total returns on the Australian market hit record highs in late April 2015, and are now up by 117 per cent from the 2009 lows.