Inside the blockchain bubble

In 1998, two Stanford PhD students rented a garage from Susan Wojcicki in Menlo Park, Silicon Valley. The cost – $US1700 a month – was a fantastic deal for both parties. Larry Page and Sergey Brin went on to develop BackRub, which became Google, now Alphabet, worth $US690 billion today. Keeping it in the family, Wojcicki is the current CEO of YouTube, owned by Alphabet.

No one saw this coming, least of all Page and Brin. That same year they had pitched their PageRank technology to Yahoo, Excite and Alta Vista, the search engine giants of the era. While PageRank assessed links back to a website to determine relevance and quality, Alta Vista and Excite simply counted search terms on a web page, a system that Page and Brin thought could be easily manipulated.

Yahoo's approach was categorically worse, a kind of anti-business model that required humans to view and describe each new site in a directory. With the Internet growing exponentially, it was like using an abacus to count self-replicating calculators.

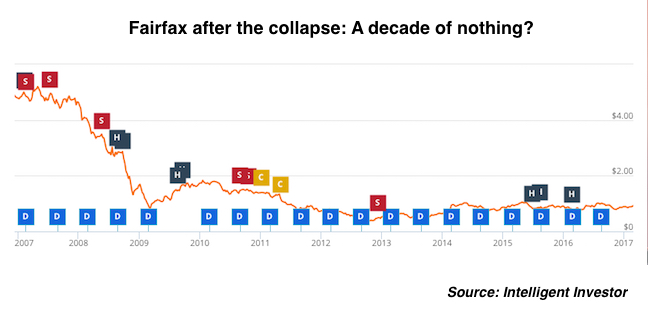

All three had what might be called a ‘Fred Hilmer moment'. Hilmer, a former CEO of Fairfax, could have bought into Seek.com.au, realestate.com.au and carsales.com.au before they became dominant. Instead, the board stuck with a dying model it couldn't see past.

These online classifieds businesses now have a market capitalisation of $18.4 billion. And Fairfax? About $2.32 billion, most of which is attributed to Domain, currently the runner-up in the Australian real estate game to REA Group. The publishing business which the company was built on is now worth next to nothing.

Yahoo, Excite and Alta Vista could have licensed Google's PageRank technology for a mere $US1 million. Instead, the lads were sent packing. Which begs the question: If the companies at the centre of a revolution can't see what's next, and who has the best path to it, what chance investors?

That was the question on my mind last week when I met the son of a friend for lunch. Jacob has just left school and is interested in investing. Not a bad start for a recent school leaver, right? Unfortunately, he's just bought his first stock and doubled his money in three weeks. Now his mates, mum and brother are in on the same caper.

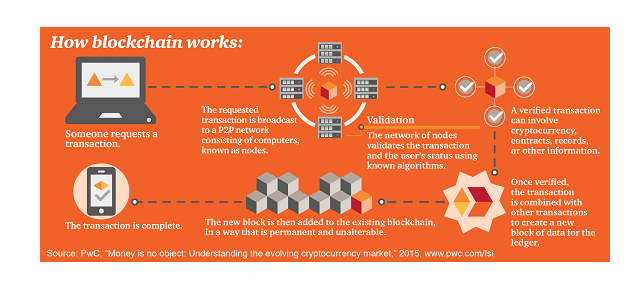

Jacob's enthusiasm is around blockchain technology and he's right to be excited by it. I'll try and explain it. Double-entry bookkeeping – assets, liabilities, income and expense – is essentially a collection of lists of transactions. The system works well but requires every business to maintain its own set of records. Now, imagine if there was only one set of records that everyone used, where no-one could cheat on a particular entry?

Enter blockchain, a distributed ledger where each encrypted piece of information cannot be subsequently modified without the digital consent of the network majority. As The Economist describes it, blockchain “offers a way for people who do not know or trust each other to create a record of who owns what that will compel the assent of everyone concerned. It is a way of making and preserving truths.”

The technology is so secure that the first application was a digital (or ‘crypto') currency called Bitcoin. But blockchain is reaching into the mainstream.

India is using it to prevent land ownership fraud. Everledger uses it to keep track of diamonds and assists in the “reduction of risk and fraud for banks, insurers and open marketplaces”. The ASX is examining it to replace CHESS. Webjet is thinking of using it to manage hotel bookings. Dubai has announced it will become the first blockchain-powered government, using the technology to eliminate 100 million paper transactions a year.

And, last but not least, just about every bank on the planet is splashing money on potential blockchain uses.

By 2020, IBM estimates 66 per cent of all banks will have blockchain in commercial production. You can understand why. The technology potentially removes the need for a middleman where two parties don't trust each other and ticket-clipping proliferates – think share registries, land registries, banks, ticket sellers, currency exchanges, medical record companies, credit cards and asset managers. But it also offers all these businesses the chance of a more secure, efficient and cheaper infrastructure. So essentially, it's both a threat and an opportunity.

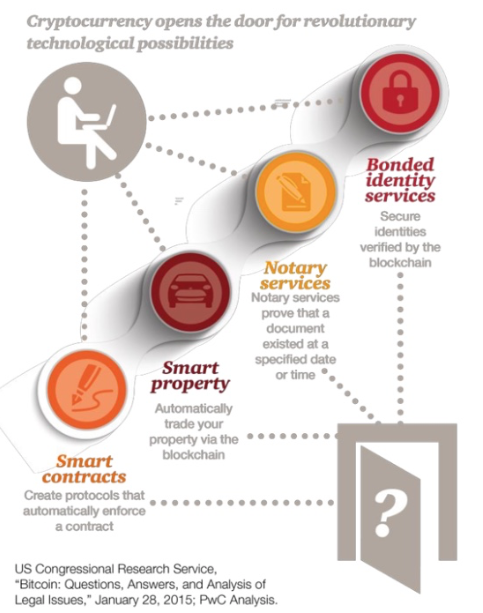

Now a new development called smart contracts has lit a fire under the blockchain belly. Like a traditional contract, smart contracts include the rules and penalties around an agreement. But the blockchain technology automatically enforces those obligations.

Right now, renting an apartment requires a middlemen, first to advertise it and then to confirm the payment of rent. With a smart contract you pay via Bitcoin and encode the contract on the ledger. Fulfillment is automatic and the transaction is verified by the network.

Blockchain, like the Internet in 1996, is going to be big. PwC estimates over $US1.4 billion ($1.8 billion) has been invested into the technology already. The CEO of Data61, a division of CSIRO, claims blockchain could "drive operational efficiency and structural change for the country", pointing out that everything from food provenance to personalised healthcare could be affected. In an interview with McKinsey & Co, the CEO of Tapscott Group argues that “blockchain can change the world”. The IMF is urging central banks to study digital currencies and the Bank of England is already doing so.

All of which is to say, Jacob and his mates are onto something, especially when you consider the number of coders around these days compared to the mid-90s when the internet was catching on.

The problem, just as it was back in 1999, is that the spivs, shonks and shysters are onto it, too, and investors have few ways to discriminate between the promise of the technology and a cast of characters leaping aboard the bandwagon claiming a particular skill or insight that will deliver untold riches.

It's possible that Perth-based PowerLedger – a “blockchain-based peer-to-peer energy trading platform enabling consumers and businesses to sell their surplus solar power to their neighbours without a middleman” – will be a raging success. It sounds like a bloody good idea and has already raised $17 million in “pre-sale”.

Investors supported Australia's first initial coin offer by purchasing a cryptocurrency with real cash. Unlike an initial public offer, there is no regulation. Investors are relying on the increasing value of the underlying currency to make money.

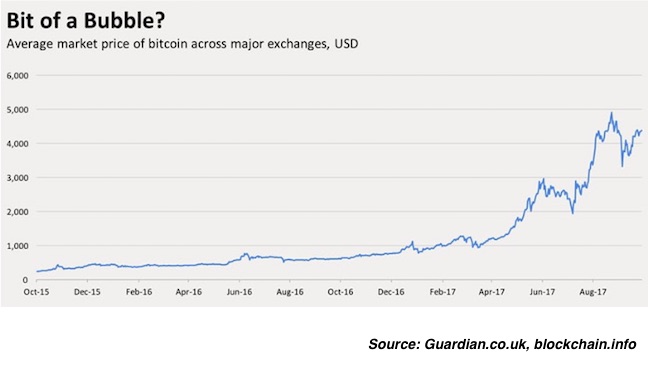

So far this year in the US there have been 176 ICOs raising $US2.7 billion. PowerLedger is Australia's first but, given this chart, I doubt it will be the last.

How do you think this crypto/blockchain thing will play out? No regulatory framework, untraceable cryptocurrencies as a store of value, anonymous trading beyond the reach of plod, and a remarkable new technology the media is going crazy over. Ring any bells?

Everything and more that we were told about the promise of the Internet in 1999 has come true. There's a fair chance the same will be true of blockchain and cryptocurrencies. The roadblocks to adoption – sheer computing power and latent security issues – will be solved, just as slow internet access and dodgy ecommerce sites have been (at least to the point no one cares all too much).

The problem for investors, and the point of the Google story where we started, is that we can predict with a high degree of confidence the adoption of a technology, but picking the companies that will make money from it is far harder.

No-one predicted that two students working out of a garage would take on the incumbents of online search and win big. Nor that a sleazy Harvard student (Mark Zuckerberg) would kill Friendster with a site that now has over two billion active users (Facebook), generating an EBITDA margin of 55 per cent on revenues of over $US9 billion last quarter.

Book Stacks Unlimited might have become Amazon because it was launched three years before it. Likewise, Swedish ecommerce site Tradera could have become eBay, instead of being bought by it. Pets.com was an idea ahead of its time that, launched five years later, might have become Chewy, which recently sold for $US3.5 billion. Even in Webvan, another dot-com bomb that raised over $US800m in capital, we can see the genesis of Deliveroo.

The winners and losers from a new technology aren't easily predicted. The point of a bubble, as we're now seeing in Bitcoin, blockchain and cryptocurrencies, is to convince investors that they are.

For what it's worth, I think bubbles are best enjoyed from a safe distance or in a schooner-sized glass. Unless, of course you're Jacob, in which case they're an invaluable learning experience on the way to becoming a great investor.